|

A Guide to Implementing the Theory of

Constraints (TOC) |

|||||

|

Clouds And Silver Linings A cloud is an elegant graphical means of displaying and

solving an apparent conflict or dilemma between two actions. It is also sometimes known as a conflict

resolution diagram; however, its correct name is a cloud. Central to the use of clouds as a problem

solving device is the assumption that there are no conflicts in nature – only

erroneous assumptions. "There must be an erroneous assumption that we make about reality

that causes a conflict to exist (1)." Let’s look at this from another perspective and

another culture – Japan; “Problems exist because people

believe they exist. If there were no

people there would be no problems.

People are also the ones who decide that a problem has been solved. Problem solving is the most typical human

behavior (2).” The apparent conflicts that do arise and which we do

want to solve are likely to be of two types (3); (1) Opposite conditions – conditions

that are mutually exclusive. (2) Different alternatives –

conditions that preclude one another. Day and night are mutually exclusive, more money or

shorter hours are different alternatives. In fact we have been using clouds fairly liberally

throughout these webpages so far to describe numerous different

situations. This should help to

underline their intuitive nature. We might use a cloud for everyday “free-standing”

conflicts or dilemmas, or as a tool to resolve the core problem or core

conflict made apparent as a result of the construction of a current reality

tree. You can learn to do clouds on

the back of a piece of paper or in you head. Such a skill can be a formidable advantage

to the user. The key point, however, is that you must want to

solve your problem or dilemma. Without

the will to solve the problem, the way to do it won’t be apparent at all. The cloud is the tool of choice in seeking to obtain

understanding and agreement on the nature of the core problem or core

conflict, especially the unstated assumptions that give rise to the

problem. This is often described as

the “direction of the problem.”

Breaking the cloud by developing an injection builds understanding and

agreement on the “direction of the solution” to the problem at hand. An injection is any new idea that we introduce into

our current reality to produce a new and desirable outcome. On the previous page we saw how Taiichi

Ohno used the 5 whys method to drill down to the core problem “Otherwise,

countermeasures cannot be taken and problems will not be truly solved

(4).” The countermeasures were his

“injection.” However, countermeasures

are limited conceptually to mitigating a currently undesirable effect by

removal or replacement with something else.

Injections go one step further – they may in fact create a totally new

and desirable step as well as mitigating the currently undesirable

effect. If the word “injection”

doesn’t do it for you, think “countermeasure” for the moment until you are

more familiar with the concept of clouds.

Think of clouds armed with countermeasures as formidable weaponry. The cloud is formidable, but it is also enigmatic. It is used both to formulate the nature of

the problem and also to formulate the direction of the solution. Previously, on the page on agreement to change, we

developed a composite 5 layer verbalization of the layers of resistance. This is what we wrote; (1) We don’t agree about the extent or nature of the

problem. (2) We don’t agree about the direction or completeness

of the solution. (3) We can see additional negative

outcomes. (4) We can see real obstacles. (5) We doubt the collaboration of

others. We discussed the subdivision of layers 1 & 2 in

more detail in the page called “more layers” accessed off the agreement to

change page. In essence we can

subdivide layers 1 & 2 into two based upon Senge’s differentiation of

detail and dynamic complexity; (1a) We don’t

agree about the extent of the

problem – detail complexity. (1b) We don’t

agree about the nature of the

problem – dynamic complexity. (2a) We don’t

agree about the direction of

the solution – dynamic complexity. (2b) We don’t

agree about the completeness

of the solution – detail complexity. The current reality tree addresses the detail

complexity of the extent of the problem.

The future reality tree addresses the detail complexity of the

completeness of the solution. The

cloud, however, addresses both the nature of the problem and the direction of

the solution. As such it is a

transitional tool or a pivot in the whole process. If we accept that there are two distinct

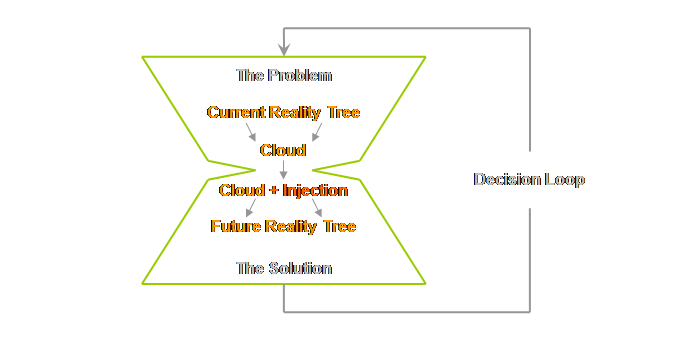

phases to the cloud it is much easier to understand. We can draw a simple model of this situation.

There are interesting parallels between this

decision loop and the OODA “Loop.”

Colonel John Boyd developed the concept of the OODA Loop (observe,

orient, decide, act) as a way to describe his ability to win a dog-fight –

any dog-fight – in 40 seconds (5). The

OODA Loop (and maneuver warfare) has found its way into the more general

business literature as well. Although

in the process it has sometimes lost its proper attribution. For example, “The U.S. Air Force has

studied … (6)” or mention of the use of “commander’s intent” in the U.S. Army

and Marines (7). Boyd is in the

background, but not acknowledged, and we are the poorer for it, we fail then

to see the continuity of the theme. Boyd’s argument is that he could out-maneuver his

opponents by working within his opponent’s decision cycle. As we shall see this works at two

levels. The first level is that the

sooner that we can define the cloud and break it with an

injection/countermeasure, the more likely we are to be able to work inside of

our opponent’s business cycle, and the more likely we are to succeed on our

own terms rather than that of our opponents.

We could consider this incremental

improvement. The second, deeper level,

is that if we understand the dynamics of the environment in a different and

more realistic way than our opponent, then once again, we can work inside our

opponent’s decision cycle but this time at a more elementary and deadly level. This is fundamental

improvement. The OODA Loop has much to offer although it is often

misinterpreted. If you already

understand clouds and wish to understand the OODA Loop better, then click here. Otherwise

don’t worry we will return to the OODA page further on when we discuss

strategy – in particular; paradigms. How many of us have sat around a table while some

consultant told us to “think outside the box.” Ha, whatever that meant! Yeah, like this is a special time for

thinking outside of the box before we all go back to work inside of one as

usual. Cynicism aside, what if we got rid of the box

completely? Then we wouldn’t have to

think about it at all. What if the

cloud was the tool that let us do that in a structured way? If you would like to see a graphical

representation of this click here. In any

case, come back here after you reach the end of this page. It is a valuable mental image for

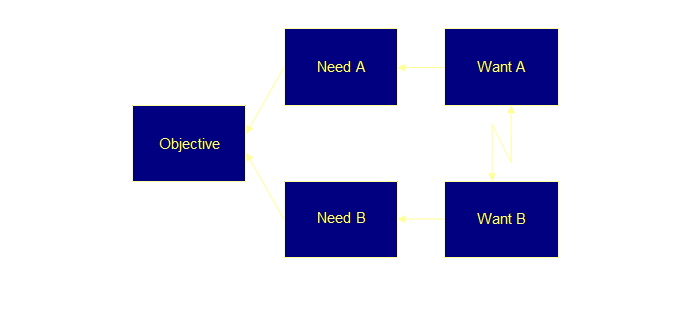

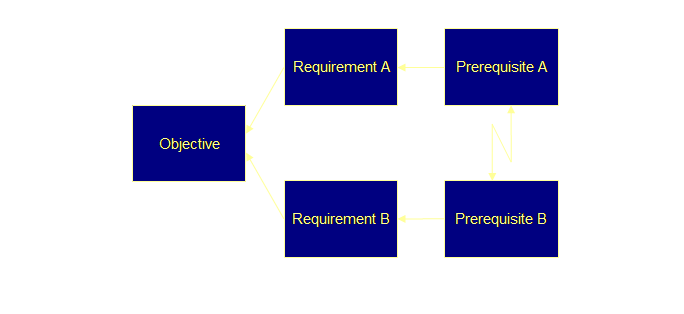

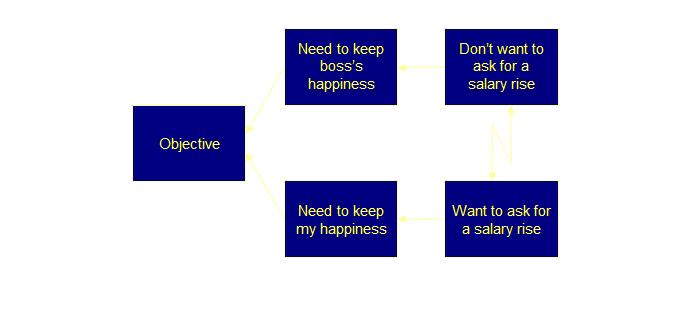

understanding clouds. We construct a cloud out of 5 entities (3, 8, &

9). The first is a common objective

which we want to satisfy. In order to

satisfy the common objective it is necessary that we fulfill two needs. In order to satisfy the needs it is

necessary that we fulfill the two wants.

However, the two wants are in conflict with each other as indicated by

the arrows

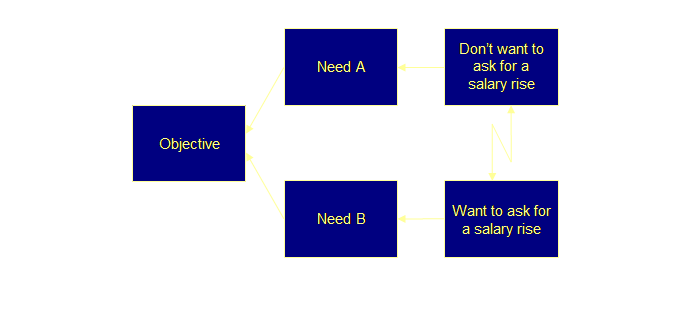

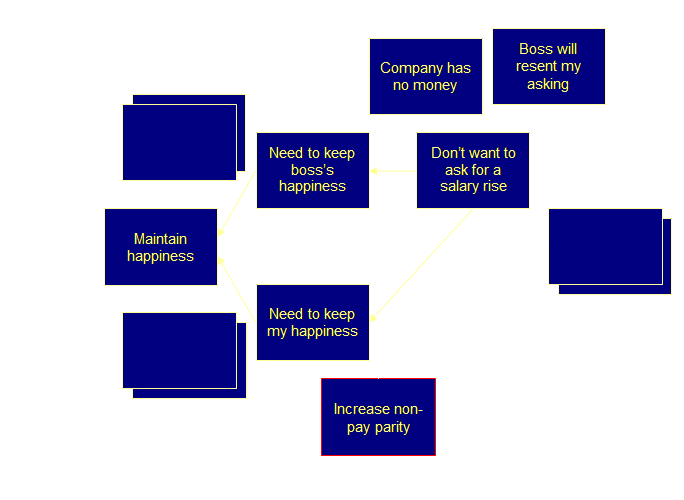

So let’s do this by using a real example that is

familiar to most people. Have you ever

had the conflict “ask for a wage-salary rise/don’t ask for a wage-salary

rise? I’m sure there most people

have. Let’s draw it.

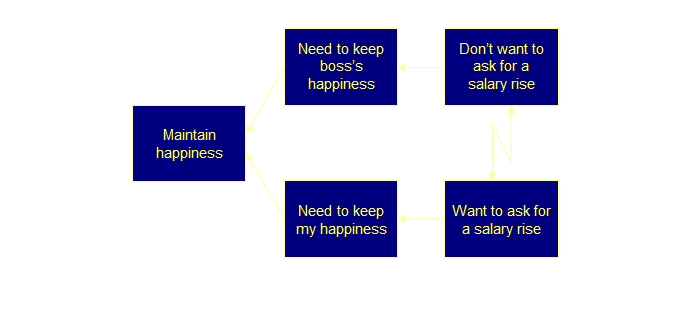

We read it from objective to need to want as

follows, you will need to learn the form of reading them, and soon it will

become second nature. In order to

maintain happiness it is necessary to keep the boss’s happiness. And in order to keep the boss’s happiness

it is necessary to not ask for a salary rise. Looking at the other side. In order to maintain happiness it is necessary to

keep my happiness. And in order to

keep my happiness it is necessary to ask for a salary rise. Finally, we come to the conflict, the crux of the

matter. However, not asking for a salary rise and asking for

a salary rise are in direct conflict with one another. What are we going to do about the conflict? Well, Goldratt argues that there are no conflicts in

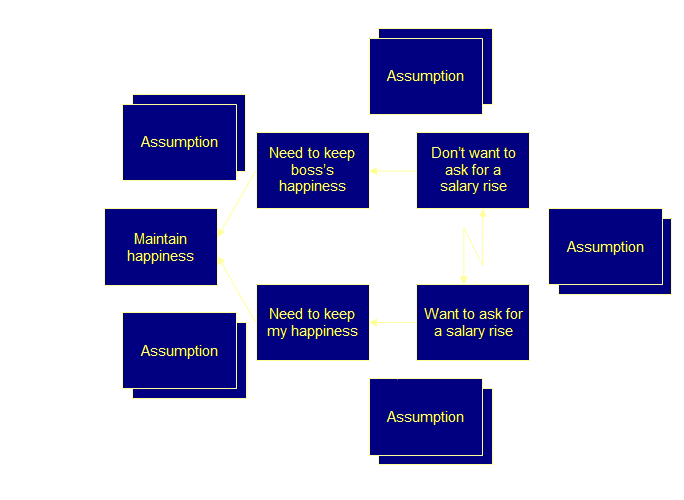

nature and therefore in business there can be no conflicts – only erroneous

assumptions. Therefore, we need to

search out the assumptions upon which our conflict is based. Where are the assumptions in the cloud? Under each of the arrows. Let’s draw them in.

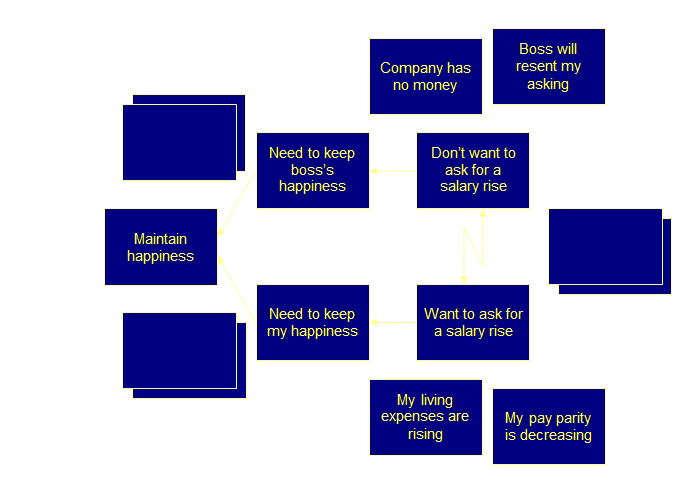

Ah, now we have something to work with. Once the verbalization is correct, we must

ask how many of these assumptions are valid, how many are invalid, and can we

overcome any of the remaining valid assumptions with a new idea or

reality. We will call this new idea or

reality an injection. I think we must assume that it is true that the

company has no money; we saw last quarter’s results. I think that we must assume the boss will

resent my asking, the boss will be in a difficult position of turning my

request down even if he wants to action it.

So the assumptions on the top side are valid and must remain. Let’s look along the bottom. “My living expenses are rising.” Are they really? Maybe, if I was more honest with myself, I

should have said that my discretionary expenses are rising. Let’s keep going. “My pay parity is decreasing.” Ah this looks like a real problem. There is someone else in the company who is

younger or less experienced who is on the same or greater salary. If that is the case then it is quite likely

that I feel my expenses are rising – because I want to justify my increase in

pay parity. A possible injection then becomes “Increase my

non-pay parity.” Let’s draw these in.

You may not agree with this simple example, it may

be a little too self-virtuous. But it

does show the essentials. Identify the

needs and the common objective and the underlying assumptions. Remove any invalid assumptions and then try

to overcome any remaining ones. In

doing so you move from agreement about the core problem to agreement about

the direction of the solution. Here are some common clouds that you will most probably have experienced in business. Next we must

see how to build out from this direction of the solution to nullify all of

the undesirable effects that we listed in the construction of our current

reality tree. This is the function of

the future reality tree. (1) Goldratt, E. M., (1999) How to change an

organization. Video JCI-11, Goldratt

Institute. (2) Kawase, T.,

(2001) Human-centered problem-solving: the management of improvements. Asian Productivity Organization, pg 193. (3) Dettmer,

H. W., (1998) Breaking the constraints to world class performance. ASQ Quality Press, pg 104. (4) Ohno, T., (1978) The Toyota

production system: beyond large-scale production. English Translation 1988, Productivity

Press, pp 126-127. (5) Hammond,

G. T. (2001) The mind of war: John Boyd and American security. Smithsonian Institution Press, 234 pp. (6) Stalk, G.,

and Hout T. M., (1990) Competing against time: how time-based competition is

reshaping global markets. The Free

Press, pp 180-183. (7) Wheatley,

M. J., (1999) Leadership and the new science: discovering order in a chaotic

world (2nd. edition). Berrett-Koehler

Publishers, pp 107-108. (8) Dettmer,

H. W., (1997) Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints: a systems approach to

continuous improvement. ASQC Quality

Press, pp 120-176. (9)

Scheinkopf, L., (1999) Thinking for a change: putting the TOC thinking

processes to use. St Lucie Press/APICS series on constraint management, pp

171-191. This Webpage Copyright © 2003-2009 by Dr K. J.

Youngman |