|

A Guide to Implementing the Theory of

Constraints (TOC) |

|||||

|

That “P” Word – Paradigm What about that “P” word – paradigm? This is a word that we haven’t seen very

much of in the previous pages. What

could be the reason for avoiding such a common word? Well, maybe, because it is just such a

common word – in business. And maybe

also because it has lost its real meaning – in business. We have used words such as; mental models, views or

maps of reality, schemata,

insights, intuitions, hunches, beliefs, and perceptions, but these are all personal

entities. A paradigm describes a common

view of reality shared amongst a great number of people. To further understand the real meaning of

the word however, we must return to the origins of the term, to science. Thomas Kuhn coined the word “paradigm” to explain

how people who study the natural sciences could, as a group of individuals,

work independently upon a problem and yet maintain general agreement about

the nature of problem they are working on.

In contrast many of the social sciences are in a “pre-paradigm” stage

of “schools” where various groups of independent practitioners can’t even

agree upon the nature of the problem that they are investigating. Kuhn wrote (1); “

... I was struck by the number and extent of overt disagreements between

social scientists about the nature of legitimate scientific problems and

methods. Both history and acquaintance

made me doubt that practitioners of the natural sciences posses firmer or

more permanent answers to such questions than their colleagues in social

science. Yet, somehow, the practice of

astronomy, physics, chemistry, or biology normally fails to evoke the

controversies over fundamentals that today often seem endemic among, say,

psychologists or sociologists.

Attempting to discover the source of that difference led me to recognise the role in scientific research of what I have

since called ‘paradigms.’ These I take

to be universally recognized scientific achievements that for a time provide

model problems and solutions to a community of practitioners.” The existence of pre-paradigm “schools” is, of

itself, not a problem, it is simply recognition of a certain stage or

state. All of the scientific

disciplines had pre-paradigm stages, some extending back into pre-history. These stages are a necessary part of the

development of a paradigm. Competing

schools exist until a problem is sufficiently well defined that it becomes

the dominant shared view of the participants.

In business at the moment the best illustration of a pre-paradigm

stage is probably strategy where, currently, there are some 10 different

schools of thought (2). Schools arise because;

“In the absence of a paradigm or some

candidate for paradigm, all of the facts that could possibly pertain to the

development of a given science are likely to seem equally relevant (1).” In business applications the pre-paradigm schools

that exist today within strategy, and perhaps also sales and marketing, are

exceptions. Much of current business

is conducted in accordance with widespread, strongly held, and internally

consistent views. Many would argue

that these represent paradigms.

Indeed, we will argue here that there are at present two concurrent

paradigms afoot. We have essentially

done as much in the pages on strategic advantage and the OODA Loop, although we have so far

continued to call these concurrent ideas “approaches.” Let’s now use the criteria of Kuhn, the

originator of the concept of paradigms, to test the “fitness” of these

approaches to his description of a paradigm. And let’s add that, although there are two paradigms

afoot at the current time, they are essentially mutually exclusive. The newer paradigm may have built upon the

older pre-existing paradigm as we shall see, but unless a person is of “two

minds” we can not hold on to more than one paradigm at one time. Moreover, paradigms are not whims or

fashions, they are held dearly and given up reluctantly, and once given up they

are not revisited. If you had a “paradigm

change” this morning then it probably wasn’t a paradigm at all. When people talk about “having to give up” or

“overcome” so many paradigms, then they are confusing the detail of the

interpretation that arises as a consequence of a paradigm with the paradigm

itself. They are confusing policies

with paradigms. A paradigm is

characterized by achievements that are “sufficiently unprecedented to attract

an enduring group of adherents away from competing modes of … activity.” While at the same time it is “sufficiently

open-ended to leave all sorts of problems for the redefined group of

practitioners to resolve.” Kuhn

considers that achievements that share these two characteristics should be

referred to as paradigms. Furthermore

he recognized that a group of adherents can “agree in their identification of a paradigm without agreeing on, or even

attempting to produce a full interpretation

or rationalization of it. Lack of a standard interpretation or of an

agreed reduction to rules will not prevent a paradigm from guiding research

(1).” Before we delve any further into investigating the

fitness of our differing approaches as paradigms, it is important to remember

that we as individuals can not hold multiple paradigms at once. This website is written from the point of

view of one of the approaches – the new approach; therefore it is sometimes

difficult to completely argue for all aspects of the older and preceding

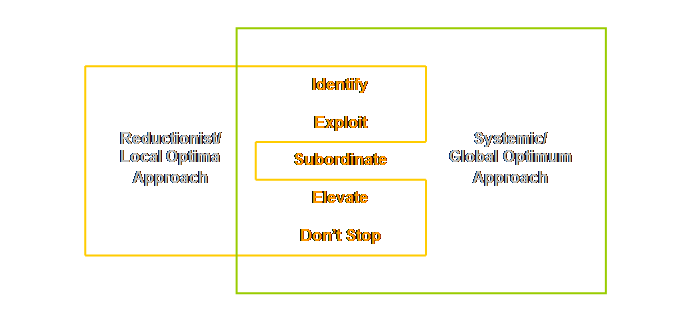

approach. In the introduction we presented a simple matrix

that served to combine two key concepts, the concept of complexity and the

concept of optimization.

From this simple matrix we deduced two diametrically

opposed approaches. We have

consistently used these two approaches to frame, and to reframe, our view of

our organizations. The two approaches

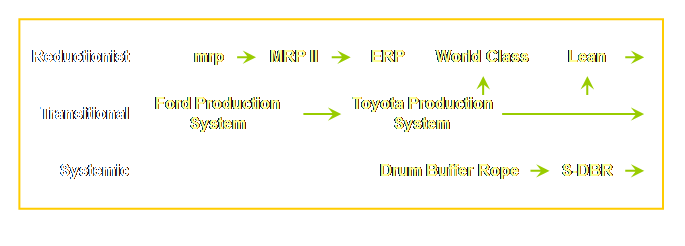

are; (1) Reductionist/local optima approach. (2) Systemic/global optimum approach. We have been

able to consistently use these two approaches, these two views, these two

lenses, to classify and to sort the various business methodologies that we

have examined in these pages. Let’s

now collate all the different activities that we have examined (plus a few

more from project management for good measure) and put them in a table sorted

against the two approaches. Let’s draw the

table.

Surprisingly, when we do this we find that there are

not only the two end-member approaches; but that there are also a number of

methodologies that seem to be transitional between the two. The transitional methodologies might be

described as having a strong leaning towards a systemic approach but still

retaining vestigial reductionist parts.

The transitional methodologies are enigmatic; we might “feel” as

though they ought to be systemic and yet we “know” that they are not. And while we may “know” that they are not

systemic, we may not know why they are not systemic. As we develop and tighten our definitions

of what is systemic and what is not, we will be able to better understand

this transitional class as well. We have characterized our two approaches in terms of

the methodologies that they embrace over a number of different aspects of

organizational activity. We know which

methodologies are characteristic of the reductionist approach and we know

which methodologies are characteristic of the systemic approach. We are almost ready then to test our two

end-member approaches for “fitness” as paradigms. It would be useful first, however, to

remind ourselves of some the developmental sequences that we inferred in

earlier pages. Let’s do that. In earlier pages on accounting for change,

production, and quality we constructed summary diagrams which, in addition to

classifying various methodologies according to our two end-member approaches,

also showed developmental relationships between the methodologies (or at

least a broad interpretation of the developmental relationships). The developmental sequence is indicated by

arrows. The arrows don’t show

duration, but the relative positions do imply priority. We can use these diagrams as guides to test

against some of the key characteristics of paradigms. Let’s start with manufacturing process/production

planning and control methodologies.

The transitional class is composed of the Ford

Production System and the Toyota Production System. Both methodologies are mass production

systems and while both are paced or synchronized to the slowest step in the

line, safety is distributed evenly throughout the system. The advancement of the Toyota system over

the Ford system is that although safety is spread throughout both, the Toyota

system seeks to substantially reduce it by increased quality throughout the

process. Drum-buffer-rope is the only truly systemic/global

optimum approach. It is both fully

synchronized, and contains reduced safety aggregated in the few key places

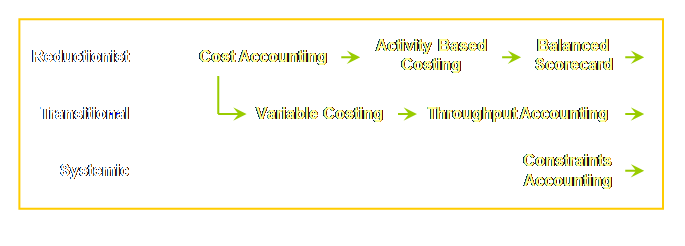

where it maximally protects the whole system. Let’s re-examine accounting methodologies in a

similar fashion.

The transitional methodologies are variable costing

and throughput accounting. Both seek

to make finer and truer distinctions between variable expenses and period

expenses; but both have their roots in cost allocation. The systemic/global optimum approach is represented

by the relatively new field of constraints accounting. Constraints accounting, for the first time,

essentially subordinates the financial information system to the strategic

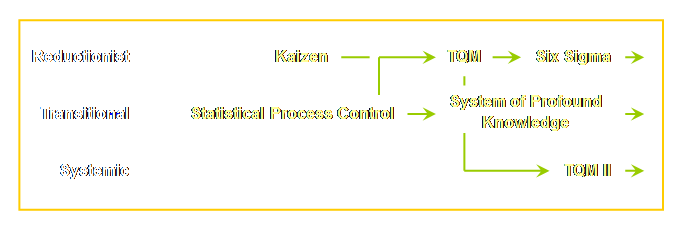

constraints of the system and thus it is a truly systemic approach. What then of the third and final set of methodologies

that we investigated – quality planning and control?

Deming’s system of profound knowledge developed out

of the much earlier work on statistical process control and is

transitional. It still uses Pareto

analysis to distinguish the areas to focus upon and Pareto analysis assumes

independence between parts in the system.

Thus it does not fully recognize dependency. Nor does the approach recognize the vast

inequivalence between different parts of the system or process. Stein’s TQM II is the only systemic/global optimum

approach. It recognizes dependency and

inequivalence and thus uses the focusing process to determine what is

important and what is not. There is,

however, a strong antecedent that the toolset is built upon – TQM. Thus, we now have some broad understanding of the

priority and developmental sequence of some of the most important

methodologies that we have addressed in these pages. We are now in a position to better evaluate

their suitability as paradigms. Kuhn subdivided paradigm-based science into periods

of relative stability which he called “normal science” and periods of change

or scientific revolution. Let’s start

at the start with “discovery,” then work through aspects of “normal science”

that occur after acceptance of discovery, and then finally let’s examine

something of the resistance of an older paradigm to the challenges of a newer

paradigm. "Discovery

commences with the awareness of anomaly, i.e., with the recognition that

nature has somehow violated the paradigm-induced expectations that govern

normal science. It then continues with

a more or less extended exploration of the area of anomaly (1).” It is much

easier to start here with the systemic/global optimum approach because discovery

of the reductionist/local optima approach most probably has its roots in the

Enlightenment movement of

late 17th and 18th Century Europe. We need to ask first; what evidence of

anomaly does the systemic/global optimum approach produce in comparison with

the reductionist/local optima approach?

Secondly we must ask; how does the systemic/global optimum approach

violate the expectations of reductionist/local optima approach? Let’s confine

ourselves to consider just two critical points at the moment, one from

production planning and control and one from accounting. From production planning and control the

anomaly is that by identifying and protecting one or just a few critical

points in a process we can substantially increase the output and decrease the

total lead time. From accounting the

anomaly is that even without an increase in output, we can substantially

increase the total profit by considering just 2 things; product throughput

(product contribution margin excluding direct labor) per unit processing time

at the critical point in the process and the total operating expense

(including direct labor) for the process. How does this

cause the systemic/global optimum approach to violate the expectations of the

reductionist/local optima approach? In

terms of planning and control it violates expectations that everything

everywhere must be scheduled by instead writing a schedule for just one or a

few entities, the constraint and any control points. It violates expectations that the process

rate is some sum of the process rates of the various stages in that the rate

of the constraint only, determines the rate of the whole process. It violates expectations of having

sufficient safety distributed amongst all points in the process in that less

total safety placed in front of a few key points will result in greater

system safety. It violates

expectations in that the non-constraints do not require scheduling, that they

do and should hold more capacity than that of the constraint, and that they

are the main determinant of total work-in-process and therefore lead time. In terms of

accounting the systemic/global optimum approach violates the expectations of

the reductionist/local optima approach that total profit is the sum of

individual product profits. Instead

total profit is determined by the sum of the throughput per unit time on the

constraint in the process. The

systemic/global optimum approach violates the expectations of

reductionist/local optima approach that operating expense (including direct

labor) can be allocated to individual products. Rather expenses are aggregated to each

process level. The systemic/global optimum approach

violates expectations of reductionist/local optima approach that operating

expense (period cost/expense) is accrued throughout the process. Rather operating expense is largely

determined by the non-constraints. By examining

just these two aspects, production planning and control and accounting, we

can say that we have positive evidence that the systemic/global optimum approach

produces unexpected and anomalous results.

The systemic/global optimum approach violates expectations brought

about by the reductionist/local optima approach. We can infer then that the

reductionist/local optima approach is a paradigm. If the reductionist/local optima approach

wasn’t a paradigm, we shouldn’t care about the anomaly and we would have no

expectations to violate. Let’s examine

then, another aspect of Kuhn’s argument. “The success of a paradigm ... is at the

start largely a promise of success discoverable in selected and still

incomplete examples. Normal science

consists in the actualization of that promise, an actualization achieved by

extending the knowledge of those facts that the paradigm displays as particularly

revealing, but increasing the extent of the match between those facts and the

paradigm's predictions, and by further articulation of the paradigm itself. Few people who are not actually

practitioners of a mature science realize how much mop-up work of this sort a

paradigm leaves to be done or quite how fascinating such work can prove to be

in the execution. And these points

need to be understood. Mopping-up

operations are what engage most scientists throughout their careers. They constitute what I am here calling

normal science. Closely examined,

whether historically or in the contemporary laboratory, that enterprise seems

an attempt to force nature into the preformed and relatively inflexible box

that the paradigm supplies. No part of

the aim of normal science is to call forth new sorts of phenomena; indeed

those that will not fit the box are often not seen at all. Nor do scientists normally aim to invent

new theories, and they are often intolerant of those invented by others. Instead, normal scientific research is

directed to the articulation of those phenomena and theories that the

paradigm already supplies (1).” Once again it

is more difficult to examine the normal science phase of the

reductionist/local optima approach than it is to examine the more recent

systemic/global optima approach.

However given that caveat let’s attempt both. Do we see an extension of the

reductionist/local optima approach, and do we see further articulation of the

approach itself? Let’s confine

ourselves once again to production planning and control and to

accounting. In production planning and

control the first automated systems were material requirements planning

systems – “small” mrp. This allowed

the automation and compression of hitherto complex and time consuming manual

planning methods in the growing numbers of larger and more mechanized job and

batch shops. Based upon the success in

material supply the approach was then extended to manufacturing resource

planning – “big” MRP and MRP II. In

turn, based upon the success of that in shop floor planning, it was extended

to supporting functions such as sales and ordering to become enterprise

resource planning or ERP. The initial

promise of mrp was extended and further articulated until it encompassed the

whole business planning function. If we look at

accounting we must start with cost accounting which successfully used direct

labor to allocate overhead costs and thus determine product costs. But we need also to be aware of a

distinction, we need to step back for a moment, back to a time before mass

production; back to a time when costing a “job” in shop was more important

than costing a product in a repetitive process. The accounting systems of the railroads

found their way into the steel companies that supplied the railroads and from

the steel companies to Fredrick Taylor.

“The system that Taylor absorbed …, made into his own, and altered to

suit his clients, was one he would apply at company after company. It gave you, monthly, a statement of

expenses, broken down by jobs labeled by letters and numbers and, later, by a

special mnemonic system. It applied

overhead not only to wages but to each machine, with time spent on the job

the basis for its proportion of the overhead (3).” Prior to accrual cost accounting, overhead

allocation was interested in jobs not products. It was a management system. “Many historians mistakenly associate the

overhead allocation methods of these early mechanical engineers with the

overhead application procedures used by twentieth-century financial

accountants. …modern financial

accountants require cost accounting to value inventory for financial

reporting (4).” This is a financial system. Given this

distinction, the acceptance of more modern cost allocation was maintained

even as direct labor became less important and was then further articulated

in the development of activity-based accounting which could use cost drivers

other than direct labor alone. The

acceptance of activity-based accounting has led in-turn to an even broader

application – the balanced scorecard approach. Each of these is both an extension of the

reductionist/local optima approach and a further articulation of that

approach. The further

development and articulation of the reductionist planning and control and

accounting methodologies suggests that the reductionist/local optima approach

is indeed a paradigm. How about the

systemic/global optimum approach then?

Do we also see an extension of this approach and do we see further

articulation of the approach within the various methodologies? Let’s examine this, again using production

planning and control and accounting. The production

planning and control the methodology is drum-buffer-rope. Drum-buffer-rope was originally applied to

linear make-to-order situations but was further developed and articulated to

apply equally to divergent/convergent flows and also make-to-stock

environments. More recently we have

seen the development of simplified drum-buffer-rope and the method has also

been extended to “project” type production or manufacturing (5). Accounting

presents more of a challenge in that the systemic methodology, constraints

accounting, is so new to the public domain that we can’t really evaluate it

yet – although we can argue that the development of constraints accounting is

nothing less than direct evidence of a further and on-going articulation of

the whole approach. Both

approaches show evidence of intolerance of other theories. Paradoxically we see this in the work of

Schonberger (6) who helped to introduced Japanese manufacturing techniques to

North American. Even though he was a

proponent of kanban for logistical scheduling to replace mrp, he considered

that MRP II was still superior for “major event” scheduling. The resistance of the reductionist/local

optima accounting methods to new theories invented by others is well

documented in other sources (7). Such reaction

is not unique to the reductionist/local optima approach. It is equally evident in the systemic/global

optimum approach. Anecdotally at

least, it appears that until quite recently, other “competing” theories were

barely mentioned by active Theory of Constraint proponents. Until recently acknowledgement of Senge’s

work, or of Lean Production, or of Six Sigma for instance did not occur

within the context of Theory of Constraints.

As an example; even though we can see allusions to Theory of

Constraints in the World Class Manufacturing literature (8) we do not see

World Class Manufacturing mentioned in the Theory of Constraints

literature. And we should add that the

allusion to Theory of Constraints was a subtle broadside at that. Hopefully as we tighten the definition of

the driver of the systemic/global optimum approach some of the reluctance to acknowledge

these methods can be viewed as due to their “impure” and transitional

nature. But we haven’t reached the

point in this discussion that we can do that yet. What we are

seeing in the production planning and control part of the reductionist/local

optima approach and the systemic/global optimum approach are the mopping-up

operations of normal science – the extension and further articulation of the

approach and apparent resistance to other ideas. This suggests that both the

reductionist/local optimum approach and the systemic/global optimum approach

are much more than just approaches; they are indeed paradigms. Let’s press

on. “during the period when the paradigm is successful, the

profession will have solved problems that its members could scarcely have

imagined and would never have undertaken without the commitment to the

paradigm. And at least part of that

achievement always proves to be permanent (1).” For the moment

let’s examine just the more recent systemic/global optimum approach with

respect to these comments. Theory of

Constraints began as a manufacturing “thing.”

It could have stopped right there and if it had, it would still have

been a very valuable contribution. But

it didn’t. We have to ask ourselves

why it didn’t stop there. The answer,

in-part, comes from one of the earlier quotes – there was a promise of success

discoverable in selected and still incomplete examples. And the answer, in-part, comes from a

commitment to the new paradigm. The

surety that something that worked for one aspect of a process here might work

for another aspect of a different process over there. Thus commitment to the paradigm has allowed

the development of not just a production application, but also a project

management application. Moreover, not

just single project environments but also multi-project environments as well,

and process/project environments.

Commitment to the paradigm has allowed the development of applications

in supply chain, both raw material supply, and finished goods. Within supply chain It has also enabled the

development of applications that are not just linear but convergent/divergent

as well. It is commitment to the

paradigm that allows these digressions to occur with some surety that the

problem will be better illuminated by the paradigm. Within the reductionist/local optimum approach an

excellent example comes to us by way of project management. And although we are not specifically

addressing project management, the example is too good to miss. Everybody knows about Gantt charts,

right? And nearly every commerce

student can tell you that they were developed in the ship building industry,

right? Gantt was involved in speeding

ship production through the Emergency Fleet Corporation – in 1917. But where did he train? He was Fredrick Taylor’s assistant from

1887 to 1893 and disciple thereafter (9).

Gantt’s commitment to standardization and documentation within the

reductionist/local optima approach learnt at Midvale Steel found its way into

project management during the First World War. This commitment of both the systemic/global optimum

approach and the reductionist/local optimum approach tells us that these are

more than just approaches; they are paradigms. However, commitment to a paradigm invariably

brings about resistance. “The

source of resistance is the assurance that the older paradigm will ultimately

solve all its problems, that nature can be shoved into the box the paradigm

provides. Inevitably, at times of

revolution, that assurance seems stubborn and pigheaded as indeed it

sometimes becomes. But it is also

something more. That same assurance is

what makes normal or puzzle-solving science possible. And it is only through normal science that

the professional community of scientists succeeds, first, in exploiting the

potential scope and precision of the older paradigm and, then, in isolating

the difficulty through the study of which a new paradigm may emerge (1).” Do we see

resistance to reductionist/local optimum approach? Sure, if you fully subscribe to the

systemic/global optimum approach. The

insistence on cost allocation by reductionist/local optima practitioners is

seen as resistance by the systemic/global optimum practitioners. The assurance that reductionist/cost

allocation is correct has seen a suite of increasingly more complex

approaches; cost accounting, activity-based costing, and now the balanced

scorecard. We see the same occurrence

in the reductionist suite from mrp to MRP II to ERP and thence to isolated

and imported elements of just-in-time as practiced in either World Class

manufacturing or Lean production. Without doubt

these reductionist methodologies, both manual and automated, are directly

responsible for a great deal of the increase in industrial productivity from

the 1900’s to around the mid-1970’s. At some point around this time however

difficulties began to become better known in both accounting (10) and

production planning (11), still the assurance that had allowed the reductionist

methodologies to succeed in the first place now began to look stubborn and

pigheaded – at least to those who were aware that a new discovery had been

made. That brings us a full circle. It brings us back to where we started;

awareness of anomaly. But now we can

be certain that our two approaches are paradigms. Let’s summarize our findings so far. There are two distinct approaches apparent in

guiding business decisions today; they are the older reductionist/local

optima approach and the newer systemic/global optimum approach. They represent concurrent, mutually

exclusive, and internally consistent views that have been developed and

articulated over a wide range of business activities. If we test them against the criteria that

Kuhn used to describe the development of paradigms in science then we are

left with the inescapable conclusion that both approaches are widely shared

and strongly held concepts. They are

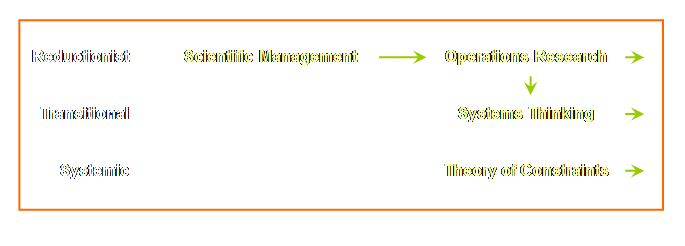

both, indeed, paradigms. We can now be quite sure that our end-member

approaches are indeed paradigms. Thus

the reductionist/local optima approach is a paradigm, and the systemic/global

optimum approach is a paradigm. But

these terms – reductionist/local optima and systemic/global optimum – are

just descriptive names. We have used

them throughout these pages to avoid introducing bias by referring to older

more common names. What then are the

more common names? Let’s draw a

generic diagram along the lines of the ones above and see.

Scientific

management didn’t really disappear.

Rather, as we have mentioned on the page on measurements, it “morphed”

into operations research – a wholly more respectable endeavor because it

required large, expensive, and complicated computers. However at the heart of operations research

is the desire to reduce the problem to its fundamental reductionist parts. Let’s consider the transitional methodologies. Here we have placed systems thinking. Previously, in the individual methodologies

we used; the Ford production system, Toyota production system, variable

costing, throughput accounting, statistical process control, and the system

of profound knowledge. All but the

last of these are application specific.

Systems thinking, in contrast, is closer to an overarching methodology

and this is the reason for including it here as the representative for

transitional methodologies. In fact, we must further address

systems thinking here because throughout this site we have treated systems

thinking as synonymous with systemism and yet now we have chosen to treat it

as if it were not. Systems thinking is

somewhat paradoxical because it uses both

simple and fundamental archetypes and yet it is still detail and data

intensive. Systems thinking is transitional

with its roots in the reductionist paradigm – most probably via operations

research. The underlying assumption is

that everything in the model and all of the data is of equivalent

significance. Senge illustrates the paradox well; “… the art of

systems thinking lies in seeing through

complexity to the underlying structures generating change. Systems thinking does not mean ignoring

complexity. Rather it means organizing

complexity into a coherent story that illuminates the causes of problems and

how they can be remedied in enduring ways (14).” We could sum this up as follows; Dynamic complexity – isn’t Dynamic complexity isn’t complex if we know how to

locate and exploit the leverage points – the physical or policy constraints

that keep us from our goal. In effect,

knowledge of the constraints allows us to “see through” the apparent

complexity. However, locating and

exploiting the constraints is, of itself, insufficient. There is something else that we must know

about, but we will have to leave that until we determine the fundamental

driver for the systemic paradigm. What then of the systemic/global optima

paradigm? We hardly need to say that

this is currently characterized by Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints. And let’s suggest that currently there is

no other cohabitant methodology or approach that occupies this position. Again the reason will become clearer when

we examine the driver for the systemic paradigm. Scientific

management, operations research, systems thinking, theory of constraints; are

blanket terms for management philosophies within (and in-between) our two paradigms

– but what then are the core underlying drivers that allow us to make this

determination? What is it that

underlies both scientific management and operations research that makes them

reductionist? What is it that

underlies Theory of Constraints that makes it systemic – and yet precludes

systems thinking from the same paradigm? Time to delve

a little deeper. What is the fundamental driver that underlies the

world of scientific management? What

is the fundamental driver that unites the reductionist manufacturing/process

planning and control systems, accounting, quality, and project management

methodologies that we have listed? Could it be cost as in Goldratt’s description of the

“cost world?” For Goldratt the cost world is pre-occupied with operating expense and independence

(15). Certainly independence looks

like a fundamental driver, but is cost?

It seems unlikely that cost can be the fundamental driver for the

paradigm. We know this from the measurements

page; too often even while using cost as our guide we have to revert to “cost

+ intuition.” We know only too well

that we let our intuition override the driver; therefore cost can not be the

basis of the paradigm. Let’s return then to independence. Could this be the fundamental driver for

scientific management? Indirectly

maybe, but probably not directly. Too

few people have a conscious awareness of dependency and independency

(statisticians excepted). Robert

Kanigel gives us a clue to the real driver in the title of his biography of

Taylor; “The One Best Way: Frederick Winslow Taylor and the enigma of

efficiency (13).” It is that last word

that is the clue – efficiency. The fundamental driver for scientific management

(and operations research and systems thinking) is efficiency. An efficiency focus coupled with assumed

independence leads to local optimization everywhere. Goldratt of course was less equivocal; he

simply called it “efficiency syndrome.” Sometimes it is difficult to imagine how pervasive

the concept of efficiency is. Steam

engines – the very machine that powered the industrial revolution – are

inefficient didn’t you know. At the

onset of dieselization of the North American railroads steam locomotives were

derided as thermally inefficient compared to diesel and yet it is only within

the last decade that the largest diesel-electric locomotives have reached the

same horsepower as the steam locomotives they replaced 60 years ago. Yes they were thermally inefficient – but

stunningly effective. Do you remember when radios didn’t have transistors

but rather they had valves (or tubes) instead. Thermionic valves are inefficient too

didn’t you know. Yet today very simple

single-ended triode stereo amplifiers coupled to complimentary speakers are

redefining high fidelity audio. Yes

they are inefficient if wasting a few watts is a matter of concern – but they

are also stunningly effective. The concept of efficiency is so pervasive that it

infiltrates almost everything that we do.

Yet we make the error of equating efficiency with effectiveness. They are not the same thing. The driver for the reductionist paradigm can be

summarized in just one word then;

What then is the driver of the systemic/global

optimum approach? Let’s have a look. What is the fundamental driver that underlies the

world of Theory of Constraints? What

is the driver that unites the systemic drum-buffer-rope, critical chain,

replenishment, and constraints accounting methodologies? Could it be throughput as in Goldratt’s “throughput

world?” For Goldratt the throughput world is pre-occupied with throughput and dependency

(15). Certainly dependency looks like

a fundamental driver, but is throughput?

Throughput serves to focus on the open-ended potential for revenue

generation rather than the closed-end approach of reducing existing costs against

static revenue. However the financial

measure of throughput is too close to the physical measure of output, and few

businesses would fail to strive to increase their output. Thus, it seems unlikely that throughput is

the basis of the paradigm, if that were so we would fail to have a

differentiation and a differentiation surely exists. Let’s return then to dependence. Could this be the fundamental driver for

Theory of Constraints? Indirectly

maybe, but probably not directly. An

awareness of dependency arises whenever our span of control or sphere of

influence is increased from a local to a more global perspective. We have certainly stressed that re-framing

the situation from local to global is important – but it is

insufficient. Local and global optima

don’t represent mutually exclusive endpoints; they represent a sliding scale,

a continuum, from one extreme to the other.

It doesn’t seem so difficult to reframe from one extreme to the other,

given the right circumstance it is almost automatic, therefore this can’t be

driver of the paradigm. If it was

there would be no difficulty and difficulty surely exists. There is another aspect of dependence that we have

touched upon. It is a unique

perspective brought about by the Theory of Constraints through the

recognition of the existence of a singular constraint within a process. There can only be one constraint in any one

process under consideration, all other parts must be non-constraints. We must maximally exploit the constraint –

no one doubts this. But in a system of interrelated dependencies we must also maximally subordinate everything else. This is the fundamental driver of Theory of

Constraints in particular; and true systemic approaches in general. You doubt this?

Run around the house/office/factory/farm a number of times – let’s say

100 times for good measure. This is an

incredibly efficient use of your lungs and heart and muscles to name just 3

functions. So, why won’t you do

it? Because you have subordinated those

functions to the whole system that constitutes your body. At right at this moment your mind is busy

reading this text. It is so

inefficient, but hopefully significantly effective. We can summarize the driver for the systemic

paradigm with just 3 words; Subordination Subordination Subordination We can not repeat the word too many times. Moreover, subordination is fractal. It occurs at all levels and across all

disciplines. Vertically, we must

subordinate non-constraints in a production process to the constraint. In turn we must subordinate the production

process to the market if that is where the ultimate constraint lies. However, we might also subordinate some

markets to the strategy if that is the constraint to the goal of the

system. Horizontally, within an

organization we must also subordinate disciplines such as measurements and

finance and quality to the constraint and the goal of the system. Now let’s return for a moment to

systems thinking. Nowhere in the 5th Discipline

will you find an equivalent concept of subordination. This is the most compelling reason for

considering systems thinking as a transitional approach rather than as a

systemic paradigm. If subordination is so simple then how did we get

into this mess? We answered that on

the measurements page; we grew into it.

Previously – prior to the industrial revolution – local optimization

via local efficiency was a valid paradigm.

With the on-set of serial production processes we moved from local to

global optimization. Global

optimization is still achieved by local efficiency in the one place that it

counts – the constraints. This part of

the older paradigm remains. However,

now we must subordinate all of the other non-constraints and it is this

additional feature that distinguishes the new paradigm. Let’s try and make the distinction; Reductionism and efficiency is the paradigm of independent entities – our

pre-industrial past. Systemism and subordination is the paradigm of dependent entities – our

industrial present. As we moved from job shops to flow shops and from

craft to mass production, the process became more and more dependent and more

and more serial in nature. Thus

subordination became more and more important but we still mostly use the

older pre-existing paradigm of efficiency that arose in the previous craft

era. If you like; we as people have remained the same but

our mode of operation has changed – changed significantly. We are still in the phase of catch-up,

changing our behavior to match our mode of operation. There is a mismatch at present, a mismatch

that many of us can’t see. A mismatch

that maybe our previous experience and “training” precludes us from seeing. We saw that forming a systemic or global perspective

isn’t difficult for those at the top but it appeared that they were held-back

by the legacy measurements of a previous era.

In fact we found that determining the new fundamental measurement

wasn’t enough. We also needed a

focusing mechanism – our plan of attack, the 5 focusing steps. And the key to that focusing mechanism is

the one new step – subordination.

Subordination allows us to determine what is “doing the right thing”

in all circumstances. Without

subordination we haven’t moved on from the older paradigm. As we will soon see; we hear and we think that we

understand the true meaning of subordination, whereas actual implementation

experience shows that most often we don’t understand the true meaning at

all. First, however, let’s try to

further distinguish the two paradigms by looking at the differences between

them. In the following table are some of the key concepts

found in the reductionist and systemic paradigms. This table allows us to effectively compare

and contrast the two paradigms; we are able to see the similarities and

differences more clearly.

Let’s start at the start. What do we mean by reducible? Well, we could use a quote from Margaret

Wheatley to explain this;

“… machine imagery leads to the belief that studying

the parts is the key to understanding the whole. Things are taken apart, dissected literally

and figuratively (as we have done with business functions, academic

disciplines, areas of specialization, human body parts), and then put back

together without any significant loss.

The assumption is that the more we know about the workings of each

piece, the more we will learn about the whole (16)..”

Reducibility means that the whole can be known from an understanding

of the parts. To help to understand irreducibility let’s use a

later quote from Wheatley and Kellner-Rogers (17). “A system is

an inseparable whole. It is not the

sum of its parts. It is not greater

than the sum of its parts. There is

nothing to sum. There are no

parts. The system is a new and

different and unique contribution of its members and the world. To search backwards in time for the parts

is to deny the self-transforming nature of systems. A system is knowable only as itself. It is irreducible. We can't disentangle the effects of so many

relationships. The connections never

end. They are impossible to understand

by analysis.” Independence, invariance, and

equivalence of entities within the reductionist paradigm are strongly

interrelated. By equivalence we mean

that all parts of the whole have approximately equal relative capacity or

ability. Although each part may be

serially coupled to others they are independent by virtue of local safety or

buffering of some kind and their individual output is considered to be their

mean output with no allowance for statistical variation. Dependence, variance, and

inequivalence of entities within the systemic paradigm are also strongly

interrelated. By inequivalence we mean

that some entities of the whole have greater or lesser relative capacity or

ability than others within the system.

Although each entity may be serially coupled to others they are

dependent whether buffered or not, and their individual output is variable

within the bounds of statistical variation (and then some as well – things

that go “bump” in the night). It is important to take care to remember also that

the terms “constraint” and “non-constraint” don’t occur in the reductionist

paradigm at all. Combining our

discussion of inequivalence and constraint or non-constraint, Schragenheim

and Dettmer reminds us that; “What makes a constraint more critical to the

organization is its relative weakness. What distinguishes a non-constraint is its relative strength, which enables it to be more flexible

(18).” We are also reminded of the

effects of inequivalence in other ways as well. For instance; “The level of inventory and

operating expense is determined by the attributes of the non-constraints.”

Whereas; “The throughput of the system is determined by its constraints

(19).” We mentioned buffering or

safety. We might think of this

directly as safety time in projects or processes, as safety goods in supply

chain, and as waiting time/patients in healthcare. In the reductionist paradigm where

everything is equivalent, so too should the safety be equivalent and thus

spread locally, liberally, and therefore equally throughout the whole. In the systemic paradigm where entities are

inequivalent, so too should the safety be inequivalent. The maximal safety is found at the location

of the least equivalence thereby protecting the whole system. Protecting the whole system is

analogous to exploiting the whole system. Exploitation is the only word that

is common to both groups. Common and

yet its meaning is different. In the

reductionist paradigm where everything is equivalent we should not be

surprised to find that we must exploit each part equally. In the systemic paradigm where entities are

inequivalent we should not be surprised to find that we must exploit each

part inequally. In fact the English

language does not allow us to say this.

Thus maximal exploitation must be reserved, like maximal safety, for

the least equivalent entities – the constraints in the system. The word we must use to describe the

inequal exploitation of non-constraints is subordination. Just as exploit is the only word

common to both paradigms; subordinate is the only word unique to one of the

paradigms. Subordination is unique to

the systemic paradigm. Subordination

as we know means doing what we should do and not doing what we shouldn’t do –

according to the system’s perspective. The fact that the word “exploit” occurs in both

paradigms and the word “subordinate” only occurs in the more recent paradigm

is hugely significant. Let’s have a

look at this. Even though exploit occurs in both the reductionist

lexicon and the systemic lexicon, it has different meanings. Does that sound like a recipe for

misunderstanding? Oh yes. Exploit in the reductionist lexicon means

exploit everything everywhere and thereby optimize the system. Exploit in the systemic lexicon means

exploit only the constraints and thereby optimize the system. The word “exploit” is common to both paradigms and

yet its application is distinctly different.

This is the source of some of the confusion between reductionists who

indeed think that they are operating in a systemic fashion and systemists who

know that they are not. However, the

word “subordinate” offers even more cause for confusion. There is no word for subordinate in the

reductionist paradigm, the nearest word is sub-optimize and in the

reductionist paradigm to sub-optimize a part is to sub-optimize the

whole. It has a strong negative

connotation. Under the systemic paradigm, in order to optimize

the system we must subordinate the non-constraints to the constraints. As the number of constraints is few, then

the number of non-constraints is many, therefore most parts of the system are

subordinated and this is optimal. Under the reductionist paradigm, in order to

optimize the system we must not subordinate anything. As there are no constraints, everything is

viewed as important. Therefore, most

parts of the system are not and should not be subordinated and this is

optimal. Under this approach to

subordinate at any time is to sub-optimize. We must be very careful about using the word

“sub-optimize,” it only has relevance in the reductionist paradigm. In the systemic paradigm we can not

sub-optimize we can only subordinate.

In a system, subordination is optimal. We have talked about the cost world and its

assumptions of independence and equivalence, but inequivalence is hinted at

in the 80 to 20 rule – the Pareto principle.

Essentially this says that 80% of the result in a system of

independencies comes from 20% of the entities in the system – usually

interpreted to mean that 80% of the income comes from 20% of the

products. Another way to look at this

is to say that by touching 20% of the system we can affect 80% of the system. This is a statement of a power rule. Let’s summarize it as follows; Pareto Principle; the 80:20 rule

– much of the output comes from a minority of the parts. Now have you ever heard, anecdotally at least, of

companies that sought to “get rid” of the remaining 80% of the products that

give rise to just 20% of the income? They

couldn’t do it could they? You have to

have the remaining 80% of product base or client base or whatever to support

the total system. In the throughput world of dependency and

inequivalence that we are talking about, the effect of inequivalence is much,

much, greater than the 80:20 rule (13).

Goldratt suggested a ratio of more than 99 to 1. Essentially this says that at least 99% of

the result in a system of dependencies is determined by one or very few

entities in the system. By touching just 1%, the right 1%, of the system we

can affect the remaining 99%. This is

a statement of dynamic complexity.

Let’s summarize it as follows; Goldratt’s Rule; the 99 to 1

ratio – almost all of the output is determined by one or a few

parts. The one or few parts are, of course, the

constraints. For this rule to function

properly we must ensure that the non-constraints do do

the things that they should do and more importantly that they do not do the

things that they shouldn’t do – in other words that they are fully

subordinated. We, too, need the other

99% of the process base to support the total system. Let’s consider for a moment that a paradigm is

nothing more than an underlying dynamic to which we were previously blind

to. Consider also for a moment that

this new understanding of the underlying dynamic allows a whole “pile” of

previously assembled detail to be described for the first time in elegant

cause and effect (with no flying pig injections). Too often we are so close to the problem at

hand that we mistake the detail complexity for the paradigm; it is not. It is the underlying dynamic that is the

paradigm. When the underlying dynamic of continental drift

became established, then for the first time, several hundred years of

geological observation (detail complexity) could be explained in elegant

cause and effect. When the underlying

dynamic of extraterrestrial impact became established, then for the first

time, several hundred years of paleontological observation (detail

complexity) could be explained in elegant cause and effect. In our modern business structures too, the key to

understanding the paradigm is in understanding the underlying dynamic. Let’s have a look then at the implications

of our new found fundamental driver or dynamic – subordination. Quality is a necessary condition (19). Maybe, then, timeliness is also a necessary

condition – except that we don’t usually think of it as such. Both are a result of moving from craft to

mass production – from multiple parallel operations to fewer large-scale

serial operations. We have “caught up”

in our understanding of quality but we still lag in our understanding of

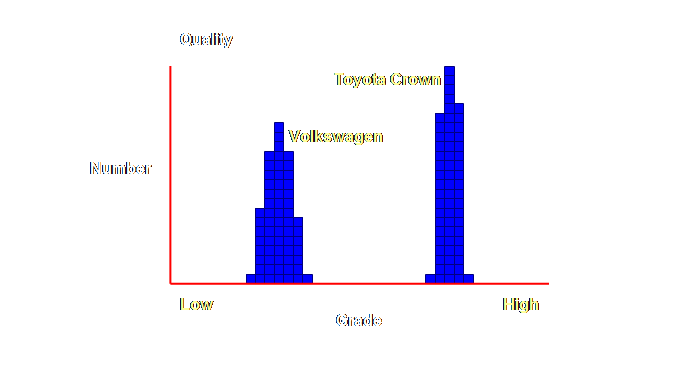

timeliness. Quality is composed of two components; grade and

variability. We verbalize grade as

either high or low. We can illustrate

this with two simple examples. A

1960’s VW beetle where quality is characterized by low grade and low

variability, and a 1990’s Toyota Crown where quality is characterized by high

grade and low variability. Both are

arguably examples of very good quality.

Shewhart defined quality as; "On

target with minimum variance (20)."

If we are to discuss quality we must discuss grade – the target – as

well.

Quality is a necessary condition rather than a goal

because we only need to have a better level of quality than our competitors

and one that our customer demands (or can be educated to want) in order to

have a competitive advantage.

Additional quality may not yield additional throughput for more than a

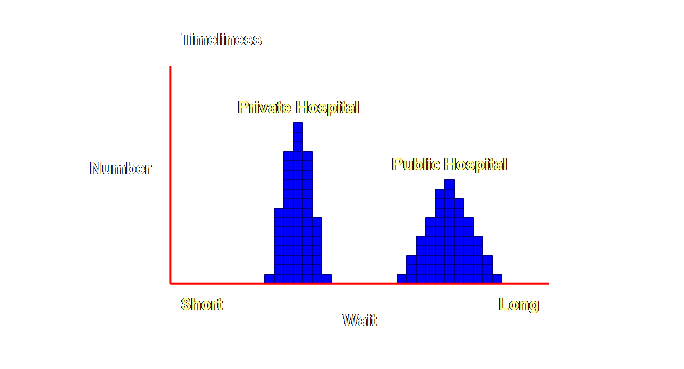

small section of the market. Timeliness, like quality, is composed of two

components; the wait and uncertainty.

We verbalize the wait as either sooner or later – shorter or

longer. Two examples? Well, how about private and public service

hospitalization. The private system is

characterized by timeliness that is both sooner and more certain, the public

system by timeliness that is both later and less certain. If we are to

discuss timeliness we must discuss the wait as well as the uncertainly.

In a craft system batches of work, if indeed they

exist, are small and the number of steps in the process is usually low and so

timeliness is not a significant issue.

In a mass production system, however, batches can be very large and

the number of steps quiet considerable and therefore timeliness becomes much

more significant. Timeliness is also a

necessary condition rather than a goal because we only need to have a better

level of timeliness than our competitors and one that our customer demands

(or can be educated to want) in order to have a competitive advantage. Additional timeliness may not yield

additional throughput for more than a small section of the market. Let’s be careful to make a distinction between cycle

time and timeliness. Let’s illustrate

this with an classical serial system – an 1850’s

tannery for book binding. In this process

hides take about a year to tan to completion, this is effectively the cycle

time – and for many people today this sounds horrendously long. However, it is possible to have multiple

hides at each stage of the process so that the end stage is producing one

hide per week or two hides per week – whatever is required. Thus we can be sure of that the wait for

the next hide will short rather than long.

The timeliness of this particular process is related to the production

rate and its variability, not to the cycle time. Having said that; where by cycle time is

affected by more than the simple production rate or duration, for instance

because of rework or additional work arising from the length of waiting, then

there is a case for treating the cycle time as a part of timeliness. It is the dependent and variable nature of modern

serial systems – our industrial present – that catapults quality and

timeliness into the center stage. Of

the two however; quality is much more tangible in nature and this helps to

explain why quality has had an earlier and more pronounced profile than

timeliness. Quality is a more obvious

factor and probably the more important factor at first. There is no point in the rapid and timely

production of sub-grade or highly variable output, however, once quality is

no longer a defining issue then timeliness may become one if a competitor

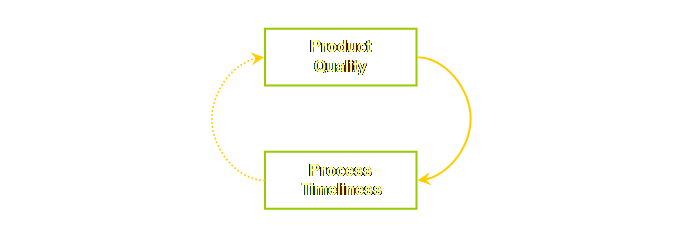

wishes to exploit it. There is also a more subtle interaction here. Increasing product quality – that is closer

to target with reduced variation causes increased timeliness. That is what just-in-time does. The continuous improvement in product

quality through the process results in increased timeliness within the

process. Thus improved timeliness is a

direct consequence of improved quality.

If you are still with me; then when we have a

timeliness issue we may look at product or process quality issues in an

effort to resolve the timeliness issue, however resolving the timeliness

issue by itself (through reduced lead times or effective buffering for

example) will not, of itself, improve product quality. This is a long way of getting around to the

point that we should not be surprised that improvement in product quality has

had better “press” until now than improvement in process timeliness. This says two things; (1) Companies that seize the timeliness opportunity have a strategic

advantage. (2) We must still continue to address product quality issues at the same

time. As businesses

have become more specialized, larger, more consolidated and integrated, and more

efficient, the aspects of quality and timeliness have become more and more

important. However, both quality and

timeliness as competitive issues have been mostly “fought out” within the

older reductionist paradigm. How much

easier it would have been if they had been fought out within the newer

systemic paradigm. Once again the organizations

that understand the new paradigm can be much more successful in utilizing

these two competitive pathways without suffering the diminishing returns of

the old paradigm. Why is this? Let’s see. Stein’s central message can be interpreted as; had subordination

been better understood then quality improvement initiatives could have been

much more rapid, focused, and successful than has been the case. Goldratt’s central message can be

interpreted as; had subordination been better understood then

timeliness and output initiatives could have been much more rapid, focused,

and successful than has been the case.

After all, subordination too, is a necessary condition. Additional levels of subordination beyond

that which is sufficient for the system to meet its goal will not move the

system any closer towards its goal.

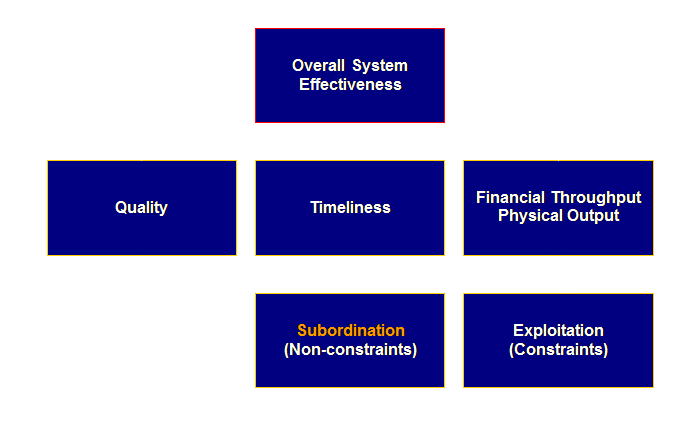

But first we must ensure that indeed we have reached sufficiency. Let’s show some provisional relationships.

If subordinating the non-constraints is a necessary

condition, then so too is exploitation of the constraints a necessary

condition. Both are necessary

conditions for moving the system towards its goal. This raises an interesting point, sometimes

we consider failure of a system to be due to the “wrong” goal having been

chosen, when in fact failure is due to insufficient fulfillment of a

necessary condition. This happens not

only at a local level, such as with insufficient subordination, but also at a

global level. We can illustrate this

effect at a global level with the goals and necessary conditions common to

businesses in the United States and Japan. The goal of corporations in each country is often

different, and we might be inclined to think that one is right and the other

is wrong, but this only misleads us.

It is the insufficient fulfillment of a differing necessary condition

in each case that is really the cause the problem. It isn’t the differing goal. We need a separate page to do justice to

this argument, you can find it here. Otherwise

let’s continue on with our two necessary conditions – exploitation and

subordination. We need to ask ourselves to what extent does the

reductionist paradigm carry over into Theory of Constraints? When most people are first introduced to

the systemic paradigm of Theory of Constraints their reference environment, their

total experience, and certainly their performance measures are likely to be

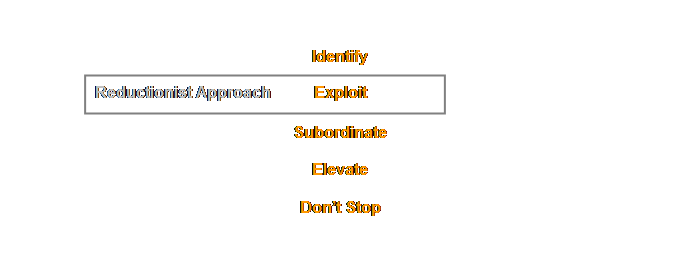

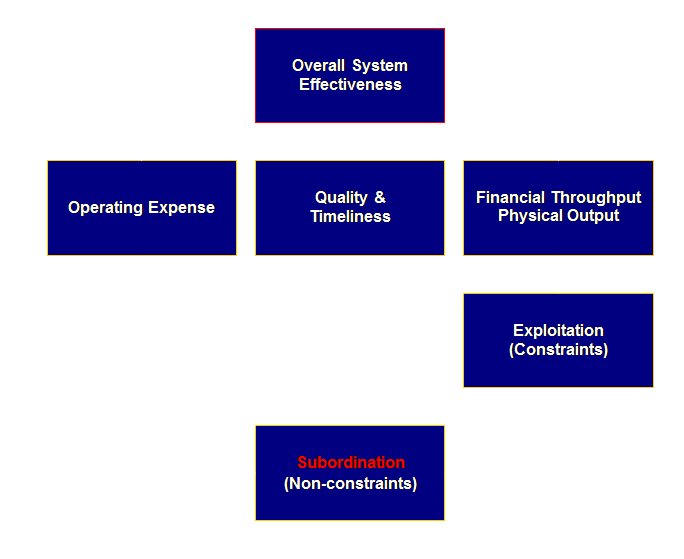

firmly rooted within the reductionist paradigm. Let’s investigate this further. We drew the diagram below on the process of change

page to show that the absence of subordination was the critical

difference between the two paradigms.

However, in doing so we may in fact have sub-consciously reinforced

that the presence of exploitation is the real issue – at least to

those operating within the current reductionist paradigm. Think about it.

Why does this occur?

Ask yourself where do we dwell when we present that plan of attack,

our focusing process? Certainly not on

subordination – most likely on exploitation.

And what is the most likely question to arise? Most probably “how do we exploit the

constraint (because we are already doing all that we can)?” This is how our plan of attack, our focusing process

looks to someone immersed in the reductionist paradigm.

Having dismissed the information to date, we can

then turn-off to the rest of the message.

The rest of the message is subordination. If you like this is a transitional

stage. People are evaluating the new

paradigm in the language of the old paradigm.

If they are listening then this is what they hear. They hear that the systemic approach is

about exploiting constraints.

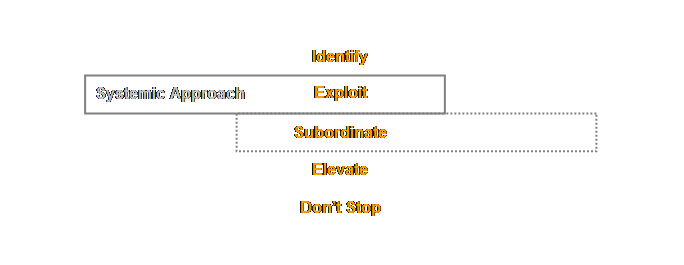

No, the real driver for the systemic/global optimum

approach is subordination. And we need

to not avoid the issue. The diagram

below is what people must see and hear.

Compare it to the diagram above.

We can summarize the two paradigms thus;

New Paradigm - Global subordination in support of the Goal

We need to be critically aware that our focusing

process will be incorrectly evaluated in the first instance according to the prevailing

reductionist paradigm. It is a case of

two paradigms divided by a common language. Think back a

moment to the provisional diagram that we drew to describe subordination as a

necessary condition for quality and timeliness. As a necessary condition we drew the entity

for subordination as a pre-requisite of quality and timeliness – we drew it

underneath those two entities. As a

necessary condition we drew the entity for exploitation as a pre-requisite of

throughput – again we drew it underneath the entity. But where did we place subordination with

respect to exploit? Beside it of

course! Why? Well, maybe, because we find it just so

hard to acknowledge that subordination is a

necessary condition of proper exploitation as well. A pre-requisite, not a co-requisite. Think about

it. Let’s redraw

the previous provisional diagram with subordination in its proper place. We have also “folded” quality and timeliness

into one entity and we have added a new entity for operating expense as an

additional necessary condition. Let’s

see what we can make of this.

Previously we drew both subordination and

exploitation as co-requisites of throughput generation. Subordination however is the pre-requisite necessary condition for proper

exploitation and moving the system towards the system’s goal. Therefore we must ensure that we draw this

correctly. The older reductionist

paradigm is so pervasive that we just don’t think about it. Cast your mind back to the traffic light analogy

that we used in the process of change page and again on the production

implementation page. We know from

experience that when we fail to subordinate properly that we begin to destroy

financial throughput and physical output – regardless of whether the output

is a tangible product or an intangible service. If we have insufficient subordination then

we fail to fully protect the system and fail to fully exploit the

constraint. Therefore we must draw

subordination as a pre-requisite necessary condition of exploitation. Sure, when we approach the issue through the five

focusing steps, our plan of attack, we must first locate the constraint

before we can know which the non-constraints are. But once we have done that it is

insufficient simply to exploit the constraint – we must firstly ensure

adequate subordination of the non-constraints. Maybe this is a source of confusion; the

sequence of discovery is not necessarily the sequence or importance of

implementation. The diagram above is more important than it first

appears. For a given level of

investment it goes a long way to addressing most of the necessary conditions

and fundamental measurements that we addressed in the page on

measurements. Consider for instance

that if we have sufficiency in physical output, financial throughput,

timeliness, and quality we must have met the necessary condition of

satisfying our customers (some might argue that quality and timeliness are

redundant here but I think that they are necessary to understand the full

picture). Consider also that if we sufficiency in financial

throughput and operating costs then we must have met the necessary condition

of profitability. And remember we

specifically pointed out the desire to decouple operating costs from

throughput by leveraging our constraints.

But what controls the operating expense? Is it the constraint? No way!

It is the non-constraints. We

mentioned this earlier on this page; the inequivalence of the various parts

of the system ensures that operating expense is determined by the many

non-constraints, not the few constraints.

Proper subordination ensures we pay no more operating expense than we

need to. You don’t believe this? Think back to when everything was treated

equivalently, the CAPEX requirements (investment and additional operating

expense to man it) will not address additional throughput. Costs go up, output remains the same. Subordination is a pre-requisite of good

operating expense control. So we have met two of the three necessary conditions

that we outlined much earlier. That

leaves just one more; secure and satisfied staff. Let’s assume that profit (now and in the

future) is sufficient for personnel security.

That just leaves satisfaction.

How do we ensure staff satisfaction?

After all, we just want to do our best. Could subordination also be a pre-requisite

and necessary condition of this? Let’s

see. We recognized that conflict, and therefore

dissatisfaction, exists within many modern organizations operating under the

old reductionist paradigm not because people are lazy or malcontents but

indeed the exact opposite – because people do want to do their best. We put it thus; Conflict

arises not because people are failing to do their best, but because everyone is

doing their best. The problem wasn’t with people; the problem was with

the map of reality. The map of reality

that we used was our old pre-industrial one.

A map of localized and independent entities. In the page on people we recognized some people

clearly have a system-wide view of the organization and yet they still fail

to develop a systemic approach to improving the system. This we could explain quite easily by two

short-comings. Firstly, the previous

lack of a focusing mechanism for dealing with constraints, and secondly, the

previous lack of a fundamental measuring system for determining progress

towards the organization’s goal. In process of change page we were able to furnish a

focusing mechanism, our plan of attack – Goldratt’s 5 step focusing

process. However, it was the critical

addition of the subordination step that allowed us to reconcile the desire of

everyone to do their best with the goal of the organization and thus be

satisfied with their input. We

co-opted something from Robert Stein; Resources are to be utilized in the creation

or protection of throughput, and not merely activated. This became our definition

of doing our best according to the goal of the system. It is the recognition of subordination, as

we have seen on this page that allows us to fully realize our systemic

intent. It is quite

apparent then, that a proper understanding of subordination is a

pre-requisite and necessary condition for staff satisfaction. What we really

need to do then, is to upgrade our rules of engagement to reflect the

importance of subordination – otherwise our rules of engagement will begin to

look as though they too are stuck in the reductionist past. Let’s repeat them here. The last line represents a new addition. (1) Define the system. (2) Define the goal

of the system. (3) Define the necessary

conditions. (4) Define the fundamental

measurements. (5) Define the role of the constraints. (6) Define the role of the non-constraints. Making the

role of non-constraints explicit is necessary if we are to move forward from

the reductionist language that we have used previously. Moreover, making the role of the

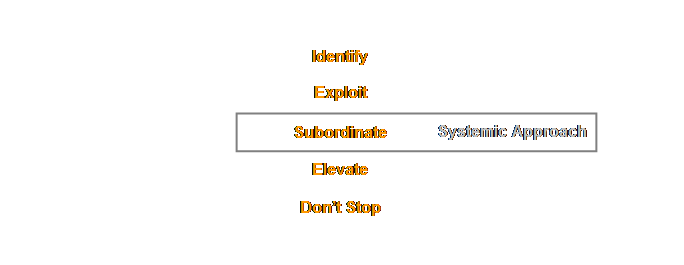

non-constraints explicit makes subordination explicit as well. How does this

modification of our rules of engagement affect the mapping with the plan of

attack that we presented in the summary to the section on Process of

Change? Well, in fact, the mapping

simply becomes better. Let’s have a

look.

In order to

define the role of the non-constraints we must decide how to subordinate the

non-constraints to the exploitation strategy of the system’s constraints. In the previous page on flexibility we recognized

that, in organic evolution, redundancy and variety led to flexibility. What are organic redundancy and variety

then if they are not other words for subordination? Organic flexibility is subordination at a

system level. Organic flexibility is

subordination at a strategic level.

This organic analogy is important. Well let’s take a couple of steps back and look at

subordination as it applies to tactical advantages first, and then we will

return to strategic advantages. We have seen how at a personal level clouds are

superb devices for tactical problems – conflicts or dilemmas. In a competitive environment they allow us

to work “inside our opponent’s decision cycle” – so called “zero-sum”

solutions. In contrast in a

co-operative environment they allow us to design “win-win” solutions. In either case they offer a tactical

advantage to the more proficient user. There is also a tactical advantage to a group of

users who can use clouds to convert individual tacit knowledge from within

the group – the assumptions surrounding the conflict or dilemma – into

explicit knowledge of the group. Goldratt

calls this verbalizing our intuition.

But wait a moment, how do we most often break these clouds? How often is the cloud broken by introducing some

aspect of subordination into the scheme of things? Never?

I don’t think so. Quite frequently? Yes, that’s more like it. If this seems strange then check it

out. It is simply a consequence of

reframing from individual efficiencies to global effectiveness. These are tactical solutions. They are very common. They are the means by which most 3 cloud

solutions are built. What then of the strategic solutions? Well they come down to taking our rules of

engagement, our fundamental measurements, and our plan of attack

organization-wide. It means fully

embracing the logistical solutions that we have described for production and

for supply chain. Most of all, it too,

means subordination. It means

maintaining sufficient flexibility in the organization that changes in the

external environment can be fully exploited. If your competitors are working within the

reductionist/efficiency paradigm of our recent pre-industrial past and you

are truly working within the systemic/subordination paradigm of our

industrial present; then your competitors won’t even know why you are more

successful than they are – even if you tell them. They can’t see it; they are looking through

a different lens. This is the ultimate

strategic advantage – in war and in commerce. Think back to the page on agreement to change where

we discussed the 5 layers of resistance.

What was the first layer? It

was that we don’t agree about the problem.

And the second layer? We don’t

agree about the solution. One of the

common verbalizations is something like; “You don’t understand, it’s actually

…..” What is this really saying to

us? Is it actually a declaration of a

paradigm block? Let’s see. We introduced on the agreement for change page a

composite verbalization of the 5 layers of resistance. It contained an implicit split in layers 1

& 2. (1) We don’t agree about the extent and/or nature of the

problem. (2) We don’t agree about the direction and/or completeness

of the solution. (3) We can see additional negative

outcomes. (4) We can see real obstacles. (5) We doubt the collaboration of

others. We subdivide out both layers 1 & 2 into two

sub-layers and we assigned them as either reflecting detail complexity

problems or dynamic complexity problems. (1a) We don’t

agree about the extent of the

problem – detail. (1b) We don’t

agree about the nature of the

problem – dynamics. (2a) We don’t

agree about the direction of

the solution – dynamics. (2b) We don’t

agree about the completeness

of the solution – detail. The core here is the dynamic complexity issues – the

nature of the problem and the direction of the solution – that revolve around

formulating the cloud and breaking the cloud with an injection. The nature of the problem can be structured

as a cloud. The direction of the

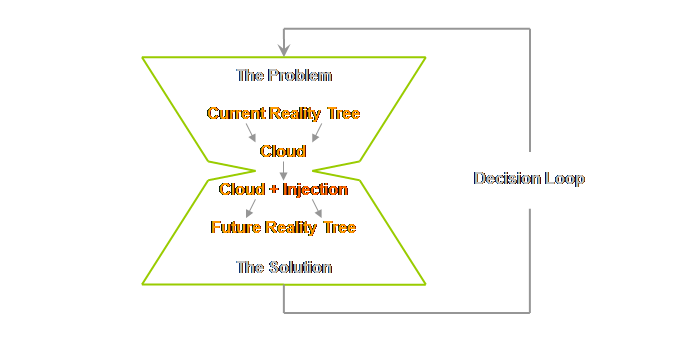

solution is therefore structured as the cloud solved with an injection. We drew a decision loop to better explain this.

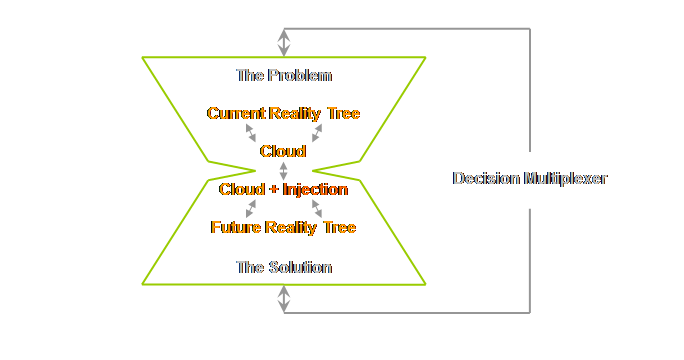

We can illustrate this more fully. On the OODA page we replaced our decision loop with

a “decision multiplexer;” we recognize that the real world and real world decisions

are incredibly messy and we ought therefore to also recognize this in our

simple model.

If all your

experience is in cost reduction and local efficiency improvement then you

will see particular solutions in your mind – solutions that have worked for

you or for others in the past. This

alone will pre-determine the nature of the problem that you see as well. It will pre-determine what you chose to

notice. Equally well if all your

experience is in throughput enhancement and global improvement then you will

see particular solutions in your mind and this will once again pre-determine

the nature of the problem that you chose to notice. The human mind is massively parallel in its

operation. It is only computer

algorithms that loop around in a repetitive and mechanistic way. It is at the level of the cloud that we break the

paradigm – and it is a one way trip.

Once it happens you won’t be able to see the problem in the same light

as you saw if before, nor will the chosen solutions ever be the same again. It is important not to confuse the development of a

paradigm with its later propagation throughout a population of potential

recipients, or its transferal from one recipient to another. The Race published

in 1986 demonstrates that the basis of systemism and subordination, the

paradigm of dependent entities, had essentially been developed by then. The production solution was making its

presence felt and there were hints of a project management solution as

well. But that doesn’t mean the

paradigm was freely able to propagate. Unlike paradigms within science, outside of science

there are often cultural or socioeconomic barriers to overcome – or at least

many more of them. In the case of the