|

A Guide to Implementing the Theory of

Constraints (TOC) |

|||||

|

A Japanese Perspective – An Explanation This page is an attempt to resolve a conundrum over

what constitutes a goal and what constitutes a necessary condition. In Theory of Constraints, “The Goal” is

fairly well agreed upon for North American commercial activities. However, repeating that particular goal in

Japan did not have the resonance that might have been expected. Over a period of time I came to believe

that another goal, one which is equally valid, operates in parts of Japanese

commerce. I want to try and describe

this more fully. Part of the problem, I am sure, is cultural. Cultural not in the selection of a goal,

but rather cultural in failure to understand someone else’s selection of their goal.

Frequently on the internet there are discussions about Toyota and the

way it operates in North America as perceived by others living in North

America but not actually working for Toyota (it would seem that many people

believe that much of Toyota’s success can be ascribed to cheap non-union

contract labor). I usually want to

scream and shout “you are not working for Toyota so how can you understand,”

followed immediately by “hey, but this isn’t even Toyota Japan this is Toyota

North America.” We are not evaluating

paradigms now, but rather cultures – wholly more messy situations. Let’s try to explain matters with a couple of

analogies and hope that one of them resonates. Take pumpkin pies and carrot cakes. My childhood exposure to vegetables was

that they were a necessary component of a healthy diet but not a particularly

enjoyable experience. How on earth

could one turn vegetables into pies and cakes? After all, pies and cakes were the exact

opposite – an unnecessary component of a healthy diet and a very enjoyable

experience at that. Well, as with

green eggs and ham, you have to try them to understand. For a Japanese example there is a fermented Soya

bean – a little like moldy cheese – called natto. About half the country thinks the other

half is crazy for eating it and the other half of the country thinks that the

first half is truly crazy for not eating it.

And very rarely will the two halves meet. Which of course is a shame for those who

don’t eat natto – they don’t know what they are missing (yes but, they will

reply, we can smell it and we are not the least bit worried about missing

out). The point is, without direct experience, often we

can’t appreciate the other sides view.

We end up stating things like “yuk pumpkin pie and carrot cake.” Really it depends upon the cultural

perspective. So, too, with goals and necessary conditions. Of course one of the advantages of inventing a

theory such as Goldratt has is that he also gets to define the terms. And if you subscribe to a particular theory

then it rather behooves you to adhere to those definitions. So let’s make sure that we know what a goal

and a necessary condition is. A goal seems to

have two important features. Firstly;

it must be open-ended, you can not have too

much of the goal (1). Secondly; the owners have the sole right to determine what the goal is

(1). What about necessary conditions then? A necessary condition

is a boundary imposed by a group external

to the owners which can not be violated (1). Looking at it from a different direction this

is a minimum condition that must be

satisfied. A necessary condition can

also be internally imposed, such as a core corporate principle or value (2). Let’s see then how this is interpreted in North

America first, and then in Japan. The North American perspective for publicly traded

companies is fairly well defined by Goldratt (1). “If a company has even one share traded

on Wall Street, the goal had been loudly and clearly stated. We invest our money, through Wall Street,

in order to make more money now as well as in the future. That is the goal of any company whose

shares are traded in the open market.” What happens then if a company is privately held? “If we are dealing with a privately

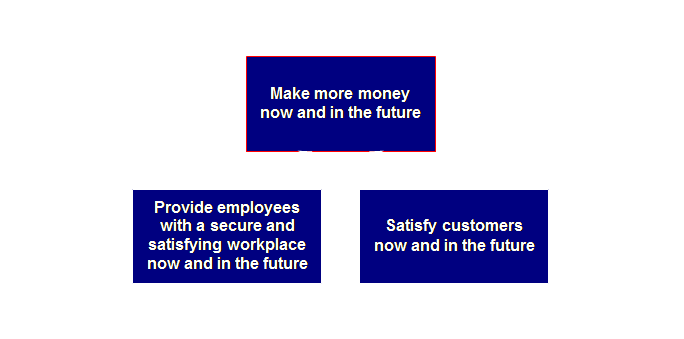

held company, no outsider can predict its goal. We must directly ask the owners.” On the measurements page we expressed the goal for a

publicly traded company as small tree with two pre-requisite necessary

conditions. However in contrast to the

measurements page where we “dropped” the “more money” from the definition,

let’s make its inclusion explicit this time.

But why do we

choose this goal? What is it about

making more money now and in the future that is important to the owners of

the organization? Well, it allows the

company to prosper and if necessary also to grow. And let’s face it, if we develop a system

that is good at producing money, won’t we want to have more of it if we are

able to expand? Just ask the share

market if you are unsure. So really

making more money is a precursor for something else – organic growth. Organic growth as opposed to raising funds

for acquisition, merger, and consolidation (aka cost cutting). Let’s draw this.

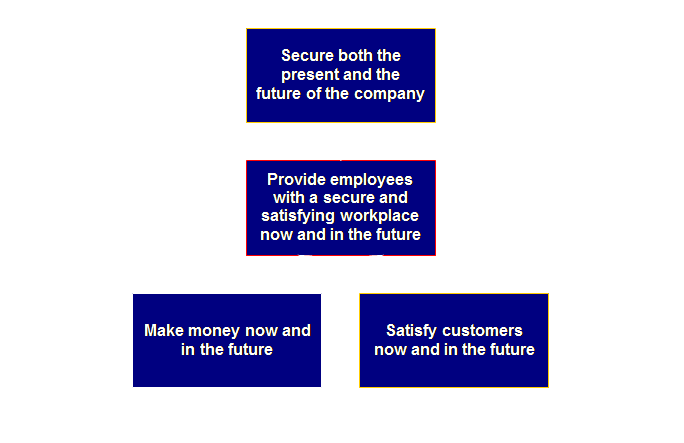

What about Japan then? Let’s see. From my point of view I feel that the goal in many

Japanese corporations, especially the so-called “founders companies” on the

2nd tier of the Tokyo Stock Exchange and a good few from the first tier as

well, is different from that of the publicly traded companies of the United

States. Sure the espoused goal might be

the same, but the goal in reality is something a quite different. Let’s have a look at this.

But isn’t this

goal heretical? Well it might be if

your paradigm is the reductionism and efficiency, it might not be if your

paradigm is systemism and subordination.

Regardless of the paradigm; it is not heretical if we are after the

same end result as in the United States. But consider

also the following. There is no

revolving door for management in Japan, once you are in you are in and you

will remain in. You make a choice for

the rest of your life in your very early twenties just as you leave

university for the first time. If your

firm “stuffs-up,” you too are personally stuffed as well. Remember too that in a nation where women

do not often hold professional positions incomes are often from a single

source. Yes, it is becoming looser more recently, some

younger people actively seek to work for “American Companies,” nevertheless

for most this is not an option especially outside of the main centers. Thus there is an imperative for security in

Japan that is lacking in the US.

Changing firms in Japan is very difficult and often quite harmful. Employment

dynamics aside; why is this goal not heretical if we are after the same

results as in the United States? Well,

let’s have a look.

What we can be

certain of is that in neither system – North American nor Japanese – is the

customer the goal. Schonberger states

with reference to Japanese inspired World Class Manufacturing that; “The

direct goal of the firm is not to produce revenue or make money. It is to serve customers (4).” Codswallop!

Satisfying customers is a means to an end, in other words it is a

pre-requisite necessary condition. It

is not the end in itself, it is not the goal. In Japan the

customer and the guest are described by the same word. “We have guests in the factory” is how

Japanese usage describes such things.

And, well, if we had more guests, or if they would just pay us a

little more for our product, then we could justify borrowing enough money to

buy that neat new computer numerically controlled machine that we saw at the

show last year! Satisfying the

customer is not the goal in either system.

Its transportation to the U. S. as a goal, and its

institutionalization in various national award criteria, is the result of

misunderstanding. Ah, but I can hear you say, employee security and

satisfaction can’t be the goal because it’s not open ended. Oh really?

Then consider the following for a moment. A feature of Japanese corporate life is the twice

annual bonus payment. One half at New

Year and one half in mid-summer. Parts

of the economy revolve around these periodic lump payments. Generally these range from a standard 3

months salary to about 5 months salary per year. Now suppose you were on 3 months and were

offered 4, would you refuse it? I

doubt it. And once you were on 4

months would you limit yourself to that if the company continued to produce

more cash? Probably not. An additional month’s bonus each year would

make you more satisfied and certainly more secure. Employee satisfaction and security is open-ended. You can’t have too much. There are other non-cash incentives that add to

satisfaction and security for employees-for-life. Many corporations will have limited amounts

of company housing for younger families.

New unmarried employees will almost certainly take advantage of

company hostels because they are so much cheaper than the open market. There are usually special company deals on

hotels in popular holiday areas, the company ski lodge, the company mountain

house and so forth. In the context maybe

we should expect nothing less. Is it

open ended? It can be. There is one other aspect. Employment-for-life or at least allegiance

to the firm carries with it a need to expand.

Currently, most corporations pay seniority-based pay. Year after year the total base pay of the

corporation increases as the workforce ages.

Expanding the firm broadens the age base with increasing numbers of

younger graduates and reduces this effect.

Another need to expand comes from the need to find meaningful

positions for everyone. Unlike the

Army for instance where it is “up or out” when there is no out, you have to

keep creating “up and across.” For

many Japanese firms kaizen has enabled them to grow markets in size, type,

and geographic dispersion. Expanding

the firm means security. Once again

there is an imperative that does not exist in North America where up or out

(to a better firm) operates. Well, if the goal in this case is indeed open-ended,

then surely it is not what the owners of the system have declared as the

goal. Well let’s see. We need to look at the corporate structure

in Japan and the role of the banks. "At an average U.S. publicly

traded company, the board of directors has about 13 members, only two or

three of whom are from inside the company.

The remaining are appointed from outside." "But at an average company in

Japan, there are no outside board members.

The board often has more that 20 members and usually they all are

executives engaged in daily operations of the company (5).” Thus we can see that the governance structure of

Japanese corporations is somewhat different from what we would expect in

North American or European models.

Let’s continue. “The board rarely dismisses the

president because members have long been subordinate to the president, who

effectively has the final say in appointing board members, subject to the

approval at a shareholders' meeting. Cross-shareholdings also still account

for much of the total outstanding shares of the Japanese companies, and there

are fewer institutional investors on the market than in the U.S. Management

teams thus feel relatively little pressure from the stock market and

shareholders, a situation that allows them to operate at low return-on-equity

ratios (5).” Thus active

institutional investment in publicly traded companies is much less than in

North America and representation by such shareholders is non-existent. We can see some of the institutionalized

disenfranchisement in the fact that about 70% of publicly traded companies

which close their books in March have their annual shareholders meeting in

June – June the 27th to be exact!

Racketeers might be the stated reason for this coincidence (6) but I

invite you to consider this more fully. Tightly held ownership of shares is not unique to

Japan. For a North-American example we

can turn to Cummins Engine Company. By

developing tightly held ownership rather than cross-ownership Cummins Diesel

was able, in the early 1990’s, to fend-off the “efficiency” of the markets

through selling shareholdings to Ford, Tenneco, and Kubota; all of whom had

mutual interests in Cummins’ success.

It was a strategy to secure “patient capital” and achieve the position

of a “private company with public ownership.”

It is acknowledged that making the interests of the company and

several key customers congruent actually made the company paradoxically more

“Japanese” in its mode of operation (7). It was suggested in the quote that management feels

relatively little pressure to increased return-on-equity. Let’s examine this further. “According to U.S. ‑based consulting firm McKinsey

& Co., the average ROE of listed Japanese companies, excluding financial

institutions, has fallen from a peak of 16.6 percent in 1969 to 2 percent in

1999. The ROE of U.S. firms, on the

other hand, has gradually increased over the same period, hitting 23 percent

in 1999 (5)." If debt finance is important, then what is the role

of the banks in Japan? Here is one

view (8). "We have entered the realm of the

absurd, when it comes to credit and risk," said Takehiro Sato, economist

and executive director at Morgan Stanley. "Banks continue to be

nonprofit organizations whose sole purpose is to provide a safety net against

unemployment (by carrying ailing companies)." So who are the owners? The owners of debt financing, the banks,

are essentially ensuring that the goal of employee satisfaction and security

through continued employment is met.

The owners of equity finance are most often cross-shareholdings –

which amounts to owning yourself. So we could answer the question in two ways. Firstly to use Goldratt’s criterion that

the goal is set by the owners, we must agree then that the owners are the

employees – through cross-shareholding in each others’ firms and via

government sanctioned debt financing.

At least we are consistent with our definitions here. Secondly, we could consider that the portion of

shares freely traded on the stock exchange represent the real owners, but if

that is the case then those shareholders have abrogated their right to

determine the goal, and have instead assigned that right to the management. Regardless of the way we substantiate the matter it

seems fairly clear that for many companies in Japan the effective goal is the

satisfaction and security of their employees.

Moreover this goal is largely supported by society. Which goal is correct then? The North American one or the Japanese

one? Well, surely both are

correct. Correct within their

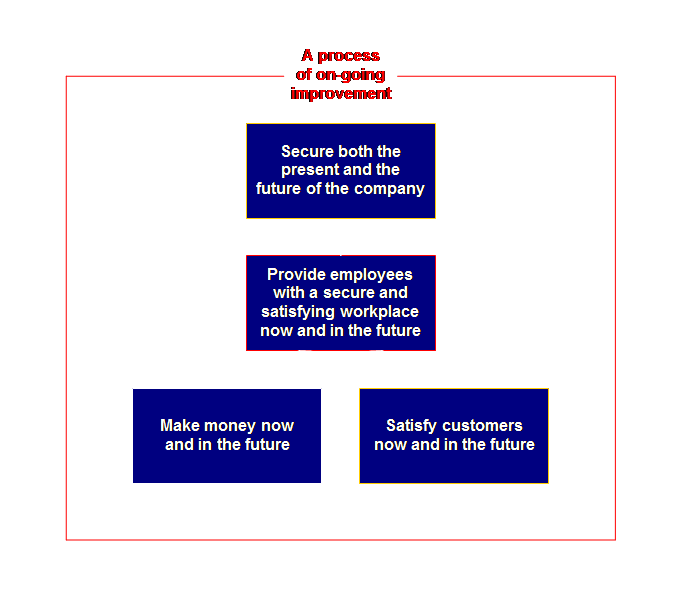

respective social contexts and correct within our prior definition. Moreover, they both create value; and they

both create a process of on-going improvement. One is maybe more capitalistic and the other more

socialistic – but then, this more like two end-points of a continuum rather

than two mutually exclusive positions.

During the 1920’s and 1930’s Japan tried a more purely capitalist

approach, but as in other countries at that time, industrial unrest was rife. Maybe the more collective model developed

in the 1950’s harks back to an earlier and more stable pre-industrial social

order. One that we see replicated to

some extent in several of the industrialized countries of Europe. Deming

certainly saw past this apparent dichotomy of employee versus investor; he

considered that management must signal their intent to “stay in business and

aim to protect investors and jobs (9).”

The accent is on investors and jobs; not either or. He addressed those comments to a North

American constituency. If neither then is incorrect as a goal within the

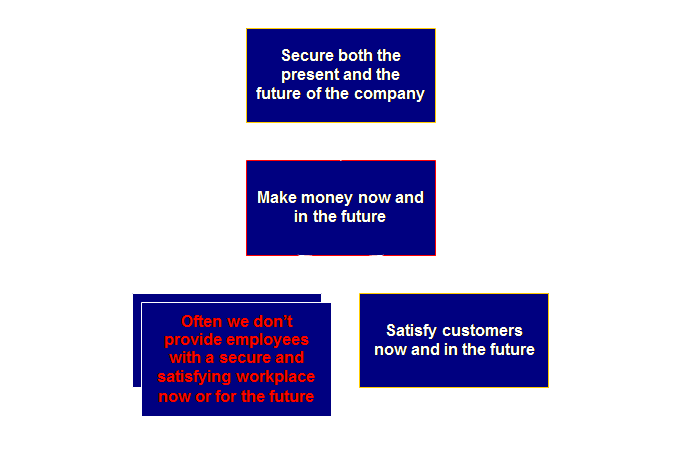

culture that it operates; what then is the problem? Let’s see. There is nothing wrong with the American perspective

– except that sometimes one of the necessary conditions is not met.

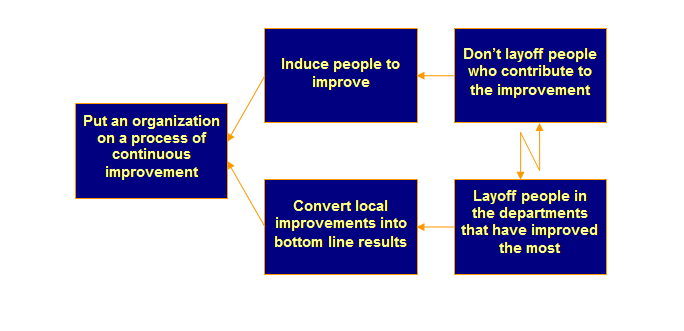

Goldratt has an important cloud that describes the

conflict that give rise to this problem.

The cloud is well known but hard to find. I know, I searched for a published

copy. Fortunately, Cox and Spencer

include it in the last chapter of their constraints management handbook (10). Here is the cloud as Goldratt originally

verbalized it.

Productivity

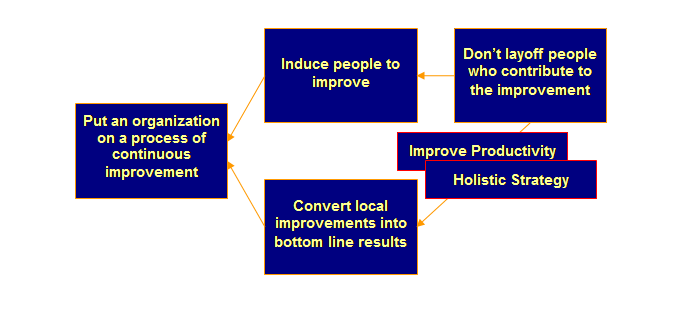

= Throughput / Operating Expense Under the systemic approach this means the

following; Improve Productivity = Increase Throughput / Maintain Operating Expense Improved productivity means increased throughput at

constant operating expense during the exploitation phase and if we have to

increase expenditure during the elevation phase then the increase in

expenditure must be significantly less than the increase in resultant

throughput. We must constantly strive

to decouple throughput from costs.

Constraints accounting shows us how to convert the investment sums

needed for the elevation phase into operating expense for management

accounting purposes so that we can evaluate the improvement using the

relationship above (11). Let’s be very clear, improved productivity does not

mean this; Improve Productivity = Maintain Throughput / Decrease Operating Expense This is the reductionist approach. This thinking is the cause of the cloud

before we broke it. This thinking is a

legacy of our pre-industrial past – leave it there, don’t bring it into the

present with us. I didn’t even want to

write it. Let’s erase it from our

minds.

Improved productivity means increased throughput at

constant operating expense – because we don’t want to layoff anyone at

all. We must

make more money for the system from the system as it exists now in order to

satisfy both of the needs. This may

eventually mean new markets or strategy.

Initially it may simply mean better exploitation of existing

circumstances. Whatever the intent, it

really means establishing an holistic approach at

the very outset of the journey towards a process of on-going improvement. Caspari and Caspari have a specific solution for

this problem which they outline in constraints accounting using a POOGI bonus

scheme (11). It is not far removed

from similar solutions in Japan. We shouldn’t

be surprised, after all the objective is the same. There is nothing wrong with the Japanese perspective

– except that sometimes one of the necessary conditions is not met.

We can build a cloud that describes the conflict

that gives rise to the problem that we observe. Let’s have a look.

Productivity

= Throughput / Operating Expense Under the systemic approach this means the

following; Improve Productivity = Increase Throughput / Maintain Operating Expense Improved productivity means increased throughput at

constant operating expense during the exploitation phase and if we have to

increase expenditure during the elevation phase then the increase in

expenditure must be significantly less than the increase in resultant

throughput. We must constantly strive

to decouple throughput from costs.

Constraints accounting shows us how to convert the investment sums

needed for the elevation phase into operating expense for management

accounting purposes so that we can evaluate the improvement using the

relationship above. We must improve productivity because we don’t want

to reduce current operating expenditure such as bonuses or benefits or divest

any of our “extra” facilities. We must make more money for the system from the system as it

exists now in order to satisfy both of the needs. This may eventually mean new markets or

strategy. Initially it may simply mean

better exploitation of existing circumstances. Whatever the intent, it really it means

establishing an holistic approach at the very outset

of the journey towards a process of on-going improvement. Taiichi Ohno understood the need to satisfy making

money and how to do it by increasing productivity (12). “What is the difference between traditional

IE [industrial engineering] and the Toyota system? In brief, Toyota-style IE is mokeru or profit-making IE.” Thus we can see that it is indeed possible

for companies in Japan to satisfy both necessary conditions in the cloud as

shown above. Toyota has been doing it

for years. Toyota is the largest corporate tax payer in Japan. You have to be quite profitable to do

that. It is imperative to make a

profit for the long-term success of the firm. We need to focus less on the goal, or the difference

between the goals and instead focus more on the insufficient fulfillment of

the complementary pre-requisite necessary conditions. Both countries; either directly or indirectly, fail

to understand the tremendous commercial advantage of increasing productivity

within their existing operations and instead look to cheaper labor rates and

develop “we can’t compete” attitudes towards other countries. This doesn’t have to be the case. It is an absolute shame that plants in the US

industrial belts can get a new die manufactured in China sooner and for a

much lower price compared to the established shop down the road. It is not the high cost of labor down the

road that is causing this disparity.

It is something else. “In 1986,

the Japanese industrialist Konosuke Matsushita predicted that America would

lose in the race for international markets because it was infected with a

disease, the disease of Taylorism (13).”

The disease of least cost. In a

business the quickest way to realize cost savings is to lay-off staff. To lay-off staff destroys one of the

necessary conditions for on-going improvement. Maybe this is why North American die makers

can’t compete. Japanese companies are not dissimilar. Many Japanese corporations have in recent

years invested heavily in new plants in low labor cost countries in

South-east Asia and mainland China.

Sometimes this is to support other Japanese firms which have set up

assembly lines in the same area, often times, however, it seems to be

motivated by a fear that domestic labor will become too expensive. However, often substantial production

exists within current domestic facilities, where the investment has already

been made in plant and personnel. The

potential for increased profitability from these facilities is immense. In many ways current Japanese business practice

appears to have strong parallels with North-American businesses in the late

1970’s. Donaldson characterized the

management during this period in North-America as conservative, operating

with low debt and high retained earnings (14). Debt excepted;

conditions are similar. In North

America the low debt and high earnings retention became a target of the

changing nature of the markets which began to demand better “efficiency” – if

not voluntarily, then involuntarily through hostile take-over. Donaldson argues that voluntary internal

restructuring in response to these market changes was often much more

effective and considerably less painful than eventual externally enforced

restructuring. We could draw from this

that maybe voluntary improvements now in Japanese businesses will be much

more effective than waiting until it is externally imposed. For that matter; why restructure? Why not simply reframe. We can use the wisdom of senior management and the

enthusiasm of younger management. There is a recent excellent account of the rise and

fall of the Long Term Credit Bank in Japan by Gillian Tett. The first third of the book mirrors the

development of Japanese economic and social norms since the 1950’s and

provides an excellent context for understanding the situation in Japan as it

is today. The remaining two thirds of

the book are an insightful description of the differences in current cultural

and economic approaches between Japan and North America and the interaction

that occurs when they meet head-on. Tett, G., (2003) Saving the sun; a Wall Street

gamble to rescue Japan from its trillion-dollar meltdown. Harper Business, 337 pp. (1) Goldratt,

E. M., (1990) The

haystack syndrome: sifting information out of the data ocean. North River Press, pp 8-13. (2) Dettmer, H. W., (2003) Strategic navigation: a systems approach to business strategy. ASQ Quality Press, pg 62. (3) Kawase, T.,

(2001) Human-centered problem-solving: the management of improvements. Asian Productivity Organization, pp 118-119. (4) Schonberger, R. J., (1996) World class manufacturing: the

next decade: building power, strength, and value. The Free Press, pg 231. (5) Yoshida,

R., (2002) Japan gropes for ideal corporate governance model. Japan Times, Friday August 23rd edition. (6) Japan Times

(2003) Some firms hold early stock meetings.

Japan Times, Friday June 20th edition. (7)

Cruikshank, J. L., and Sicilia, D. B., (1997) The engine that could: 75 years

of values-driven change at Cummins Engine Company. Harvard Business School Press, pp 413-442. (8) Negishi,

M., (2003) Foreign banks excel in lending with measure of risk, realism. Japan Times, Friday July 18th edition. (9) Deming, W.

E., (1982) Out of the crisis.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Centre for Advanced Education,

pg 23. (10) Cox, J.

F., and Spencer, M. S., (1997) The constraints management handbook. St Lucie Press, pg 298. (11) Caspari,

J. A. and Caspari, P., (2004) Constraint management: using constraints

accounting measurement to lock in a process of ongoing improvement. John Wiley & Sons Inc., (draft). (12) Ohno, T.,

(1978) The Toyota production system: beyond large-scale production. English Translation 1988, Productivity

Press, pg 71. (13) Kanigel, R., (1997) The one best

way: Frederick Winslow Taylor and the enigma of efficiency. Viking, pg 486. (14)

Donaldson, G., (1994) Corporate restructuring: managing the change process

from within. Harvard Business School

Press, 227 pp. This Webpage

Copyright © 2004-2009 by Dr K. J. Youngman |