|

A Guide to Implementing the Theory of

Constraints (TOC) |

|||||

|

Sales Constraints & Mafia Offers We briefly mentioned sales constraints in the supply

chain section. A sales constraint

appears to be an external constraint – we can produce more than we can

sell. However, we also we learnt in

the introduction to the supply chain section that most external constraints

actually have internal solutions. In

fact they must have internal solutions as there is most often no other way

that we can influence the external environment. So, too, with sales constraints. We must find internal solutions if we are

to succeed. This page is not a how-to-sell page, but rather a

page that draws attention to some rather important research on selling that

shows that for larger sales the way in which we sell is most often a

considerable constraint. Nothing more

than a self-inflicted limitation on potential throughput. The research is by Neil Rackham (1) and

uses a scientific approach to the analysis of successful sales. The Theory of Constraints, of course, also

adopts a scientific approach to business and therefore we shouldn’t be too

surprised if there is some commonality and indeed synergy between these two

methodologies. So why leave this page until the very last? Why wasn’t it in the supply chain section

after the supply chain solutions?

Clearly if we have overcome our self-induced supply chain problems

then all we really have left are sales constraints. The answer is that before we could examine

sales constraints we really needed a true understanding of paradigms and we

really needed a true understanding of the Thinking Process. We have that now. We needed this understanding because we must make

some important distinctions that I believe have been muddied to date. We need to make distinctions between the

following; (1) Detail complexity sales within a

paradigm. (2) Detail complexity sales across

paradigms. In the past, in order to provide value, the detail

of selling the Theory of Constraints as a product or as a service has been

used as an example to illustrate the Theory of Constraints sales

process. This confuses many people –

we are using the process to illustrate selling the process. Moreover, the process that we are trying to

sell is the outcome of a new paradigm.

Phew! No wonder people get

confused. So let’s investigate sales

constraints from a generic point of view using the Thinking Process tools as

our building blocks. We will use these

building blocks to illustrate the process as we go. We will still eventually address the

problem within the problem; why Theory of Constraints presents a sales

constraint to itself. But along the

way I hope that a better understanding of some truly outstanding sales

research will become apparent. What, then, is a sales constraint? A sales constraint occurs when the

marketing has been completed and we have a client or customer – the buyer –

to whom we can offer real measurable value but whom we force to abandon the

transaction. Truly outstanding sales research sounds like an

oxymoron – but it’s not. It probably

sounds like that because true research into sales techniques is so very

rare. However, Rackham published the

results of research into successful large sales that is relevant to anyone in

the supply chain; the resulting methodology is called SPIN selling. While more recent “spin doctoring” in some

corporate and political spheres may have debased the acronym, don’t allow

that to detract from the message in this work. Rackham presented a simple sales model to explain

the typical sales process. Here is the

model.

The research found that in successful small sales

the two latter stages received greater emphasis. A small sale is defined as one “which can

normally be completed in a single call and which involves a low dollar value

(1).” Let’s show this preferential

emphasis and call it the small sales model.

It is drawn below.

Rackham found that successful tactics used in small

sales did not translate up into larger sales. Larger sales are characterized by a much

longer sales cycle, a much greater customer commitment, and an on-going

relationship. Maybe the differences

can be best summed up as not closing a sale but rather as opening a

relationship (1). Demonstrating features

and trying to obtain a close in a larger sale had the effect of causing sales

people to create their own sales constraints.

Sales people in successful large sales spend much more time in the

investigating phase or stage and in the demonstrating capability. Let’s call this our large sales model.

The research found that small sales and large sales

generated different needs. These were

called implied needs and explicit needs (1). Implied needs are; “statements by the customer of

problems, difficulties, and dissatisfactions.” In the language of Theory of Constraints

these are undesirable effects or “UDE’s.”

They are problems in our current reality. Problems that we would like to be rid of. Explicit needs are; “specific customer statements of

wants or desires.” In the language of

Theory of Constraints these are desirable effects or “DE’s.” They are potential outcomes in our future

reality. Problem symptoms that we have

got rid of, or that we have replaced with something that is more beneficial. Once we can see this mapping between Rackham’s work

and the Thinking Process then SPIN selling begins to look very powerful

indeed. We need to start describing

the argument using the Thinking Process as the building blocks. The number of implied needs in successful small

sales calls was found to be higher than in unsuccessful small sales calls –

in fact twice as many. In a small

sales call the buyer is well aware of the problems; the seller doesn’t spend

much time investigating these, they are small enough to be known to the

seller too – often implicitly. In fact

the seller concentrates on demonstrating capability – describing features,

and letting the buyer make the connection between the problem and the

solution. The seller then closes. One might argue that the buyer actually

made the sale. Let’s try and draw a model of a successful small

sales call.

Most often the solution to the problem will be a

simple product or service – something that the buyer currently does not have,

but that the seller does. Both the

problem and the solution are immediate both in time and space. The perceived value of the solution is

commensurate with the perceived cost or current loss arising from the

problem. Unfortunately this approach – demonstrating

capability and closing doesn’t work as the scale of the sale increases. It doesn’t work for two reasons; (1) The whole problem is no longer

immediate in time or space. (2) The price of the solution is

perceived as more than the cost of the perceived part-problem. Let’s draw a model.

In the model we have “deepened” the extent of the

problem symptoms in our current reality tree.

The buyer still knows many, but not all, of the implied needs. Some of the needs now occur in different

places or at different times, and although they may all directly affect the

buyer, the buyer no longer makes a full connection between the cause of the

problems and the resultant effects. The seller who may well see all of these cause and

effect relationships through experience with many sales may continue to

stress features which the seller now equates with increased cost of the

solution. A more expensive solution to

a problem that is perceived by the buyer to be smaller than it really

is. This is where the small sales approach

to larger sales begins to break down.

Some years ago I learnt that all buyers are

liars! Unfortunately I took this at

face value and thought that the idea reflected rather poorly upon the person

making the comment. What the speaker

actually intended to convey, but that I failed to understand, was that most

buyers don’t say what they really want.

Or, more to the point, most buyers can’t say

what they really want. Nonaka and Takeuchi describe the situation as

follows. “Most customers' needs are

tacit, which means that they cannot tell exactly or explicitly what they need

or want. Asked ‘What do you need or

want?’ most customers tend to answer the question from their limited explicit

knowledge of the available products or services they acquired in the past

(2).” In other words they can not

verbalize their intuition. As the sale

becomes larger and larger, so too does the difficulty in verbalizing the

underlying needs. This disconnect, in

time and space, between the individual problem symptoms becomes too great for

the buyer to make all the necessary re-connections. The SPIN model, through exhaustive research into

successful large sales, also comes to the same, but empirically derived,

conclusion. It recognizes the importance

in verbalizing underlying needs. Let’s

have a closer look at this model. The SPIN model addresses the deficiencies in the

small sales model by a different approach to the investigating stage and also

the capability stage. SPIN stands for Situation, Problem, Implication, and Need-payoff

(1). This comes from the questions

found to be successful in the investigating stage. We will examine this first and then look at

demonstrating capability later. Note

that the SPIN model only addresses the sale of a pre-existing product or

service, it does not address development of the product or service. In terms of the sales model the SPIN

investigating stage is as follows;

In successful large sales the seller develops the

implied needs to a much greater extent.

The seller probes the situation (defines the system) more thoroughly,

and then probes the problem. By

probing the problem more fully the seller is able to establish far more of

the problem symptoms – those that the buyer hasn’t thought to connect in time

or space. Let’s have a look.

However successful salespeople don’t stop at that

either. The research also found that

the number of questions probing for explicit needs increased substantially in

successful large sales. Remember explicit

needs are those about some future state – positive outcomes that the purchase

will bring about – the need-payoff.

Let’s add this to the model.

In successful small sales demonstrating capability

is achieved by showing features.

However in large sales this becomes one of the main causes of

resistance or objection. Again the

SPIN research found that successful sales people in large sales used features

in a different manner to successful small sales. Features in successful large sales are recognized as

one of two types; (1) Advantages – unrealized features;

features for which there is no expressed need. (2) Benefits – realized features;

features for which there is an expressed need. This is the second part of the SPIN model.

Once again the perceived value of the solution is

enhanced through the demonstration of capability without raising objection or

resistance by mentioning latent capability (advantages) to which the buyer

might perceive as an additional cost. Rackham proposed a rule to differentiate between

implication questions and need-payoff questions (or if you like implied needs

and explicit needs). He called this

Quincy’s Rule after the 8 year old who first described it (1). “Implication Questions are always sad. Need-payoff Questions are always

happy.” We could do well to remember

this rule. Sad questions are almost

always about undesirable effects (“UDE’s”) of the current reality, happy

questions are almost always about desirable effects (“DE’s”) of the future

reality. Just common sense

really. Something that 8 year olds

have in abundance. There is however something more important about

Quincy’s Rule. It allows us to

multiplex between DE’s and UDE’s. In

some cultures, in some specific situations, it can be difficult to get

UDE’s. I have seen situations where,

arms-folded, UDE’s were not forthcoming – a consequence of inter-factory

pride. And yet 3 days later the same

group spent an hour describing 20 or so DE’s – the explicit needs of the

future reality. The explicit needs of

the future reality – the happy questions, can then be inverted back to the

implied needs of the current reality – the sad questions. Let’s add this to our model.

The SPIN model is excellent in avoiding

seller-imposed limitations in the sale of large scale transactions. It addresses the limitations of porting a

successful empirical sales model for small sales into a different

environment. However, reading between

the lines, it appears that the SPIN model becomes less sufficient the more

intangible the solution is that is being offered. It is possible to train a stand-alone sales

staff using the model above. However,

what happens when the solution is a service, a rather expensive service, or

even just an idea? Rackham alludes to this when he notes that many

professionals can be quite effective salespeople (1). He ascribes this to their skill and

experience in diagnostic questioning.

Undoubtedly this is true, but I think that this misses a deeper

issue. Can you imagine what this might

be? Let’s have a look.

If we look at the SPIN model through a Theory of

Constraints lens then it is apparent that the model doesn’t address the

reservations and obstacles that are characteristic of layers 3 and 4 of the

layers of resistance. If you like, the

SPIN model addresses layers 1 and 2 only.

The SPIN model certainly makes sure that the sales person doesn’t

cause unnecessary objections about parts of the solution that the buyer

doesn’t need, but that doesn’t mean that the buyer won’t have reservations

about perceived negative ramifications, or that there won’t be perceived

obstacles – even if the buyer wants to purchase. In fact, if the buyer wants to purchase

then you can guarantee that these reservations and obstacles will arise. They should be recognized for what they are

– signs that the buyer is buying into the purchase. The ability to recognize and handle these

facets is a valuable contribution or extension to the overall SPIN model. It goes without saying – and therefore we need to

say it – that SPIN selling is the selling of detail complexity within

an existing paradigm. Let’s draw the

model again.

Using the SPIN model to overcome sales-induced

constraints is a valid mechanism for increasing throughput. But what if the detail complexity outcome is

the result of a different paradigm?

Here the rules change. This is

where Theory of Constraints applications get into strife when the SPIN model

is applied without thought. We have

only ourselves to blame. Once again we want to sell detail, the detail of the

solution to the buyer’s need. In fact

there will be little doubt that the detail of the solution can meet the

requirements of the detail of the buyer’s need. However, rather like the insufficiency

case, part of the solution will be incompletely understood. Let’s have a look at the model.

Even if the seller has very skilled professionals

who can show the cause and effect from the seller’s solution through to the

buyer’s desired results – in other words we overcome SPIN model insufficiency

– it is still very likely that we will not be able to overcome the obstacle

of “we don’t understand/believe the cause of your solution.” This is the buyer’s obstacle. And it is our problem. As sellers of this paradigm derived solution what

are we going to do? Maybe part of the response is that we can’t sell the

paradigm. We can only sell the

resultant realized benefits.

Essentially we must transfer the paradigm at no cost. Without the paradigm the resultant benefits

will not be realized. There is a

danger that the benefits may simply become unrealized advantages – features

that are expensive and for which the connection to the explicit needs becomes

lost. If we want to sell detail complexity across a

paradigm, then we must supply the effective transferal of the paradigm

first. There is no choice. If you think that there is a choice then consider

how quality as a solution was first evaluated in the U.S. It was first evaluated in cost reduction

terms – always. It was not evaluated

in terms of product competitiveness, or corporate competitiveness, or in

terms of increased throughput. The

existing paradigm blocked and (to a large extent) still blocks proper

understanding. There is nothing wrong with the SPIN methodology, we

should however be aware that it was developed within the cost-world

paradigm. Therefore we must be very

careful when using it to guide us in selling solutions from different

paradigms. To successful sell detail

complexity across paradigms, it may be necessary to use Mafia Offers. We have seen how assumptions about the

transferability of the sales methodology from small sales to large sales can

resulted in a self-imposed constraint on sales. A constraint, however, that can be overcome

by changing these internally held sales policies. But what happens when there are other

internal policies that also act as constraints to further sales? What can we do about these? Let’s no longer restrict ourselves then to just the

policies of selling, instead let’s expand our attention out to the policies

of the production and delivery and payment of the products or services that

we wish to sell. Let’s expand outwards

to these polices, and at the same time lets move back in from our indirect

sphere of influence over the buyer to the much more direct span of control

that we have over ourselves – the seller.

This is the essence of the Mafia Offer (3, 4, 5). Moreover, the Mafia Offer is no longer concerned

with only the sale of a pre-existing product or service. It may also be concerned with the development

of a product or service. In fact the

solution may be nothing more than the development of an idea that results in

a change that produces greater throughput from an existing sales stream. The underlying dynamic is that we don’t expect our

buyer to change; we must be the ones who change. After all, we have total control over

that. Well, actually, we might expect our buyer to change but it is probable that

the expectation will be short-lived.

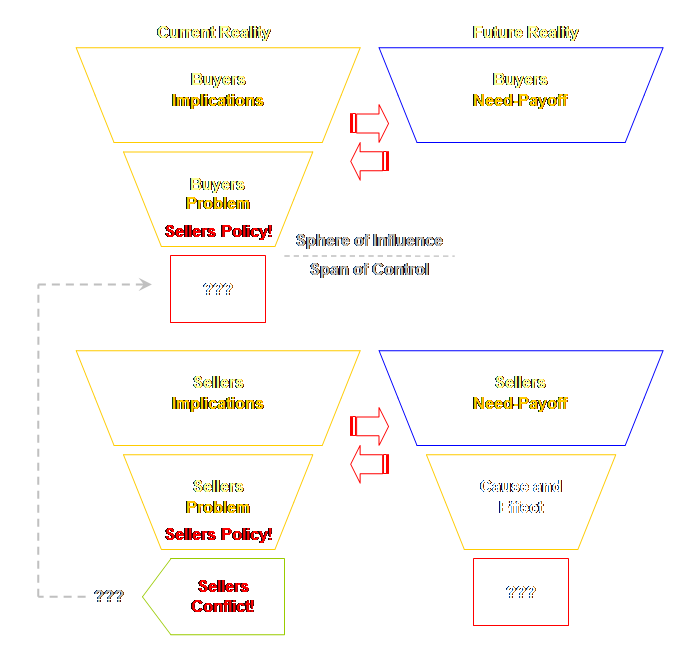

Let’s have a look at the process in more detail

The buyer’s policy might well be within our sphere

of influence, but what is the chance of changing the buyer’s policy? Not much chance at all. That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t try,

especially using the tools of the Thinking Process at our disposal. However, once we have exhausted that

possibility we should begin to have a look at our own policies.

It is important to remember that we need to know the

buyer’s problems and the buyer’s implications. Too often we will mistakenly confuse the

buyer’s problems with “our problems with the buyer.” These are not the same. There is a skill required here in being

able to stand back and look at the buyer’s problems dispassionately from our

own. Sometimes this is hard. Equally we must look dispassionately at our own

problems, once again being careful not to confuse them with “our problem with

the buyer.” Essentially we must

construct a current reality tree of the buyer and a current reality tree of

our own – the seller. Let’s have look.

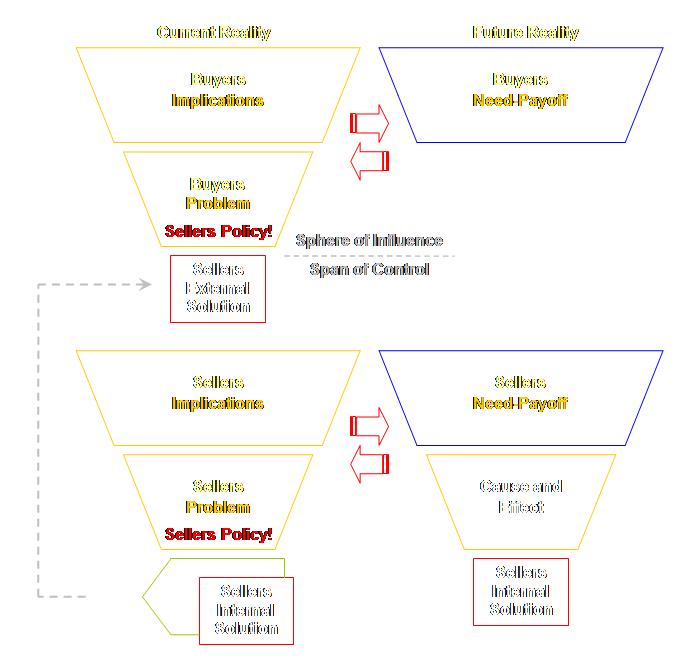

Note that the model presented here isn’t of the

development of the Mafia Offer; rather it is of the end product. Layers 3 and 4 of the layers of resistance

have an important part to play in the internal development of the offer, but

they are not shown here. By using a Mafia Offer, we reach out to the external

constraint – our market – which we have failed to change and we change

instead. The buyer’s original policy

problem may still exist but it is more likely to have been mitigated or

removed by addressing our own seller’s policy problems. We are trying to affect the buyer, not

through our sphere of influence, but rather through our own direct span of

control – success is therefore much more likely. What happens then if our seller’s policy problem is

the result of a deeper conflict? What

happens if our seller’s policy problem is the outcome of a compromise to this

deeper conflict? Let’s see.

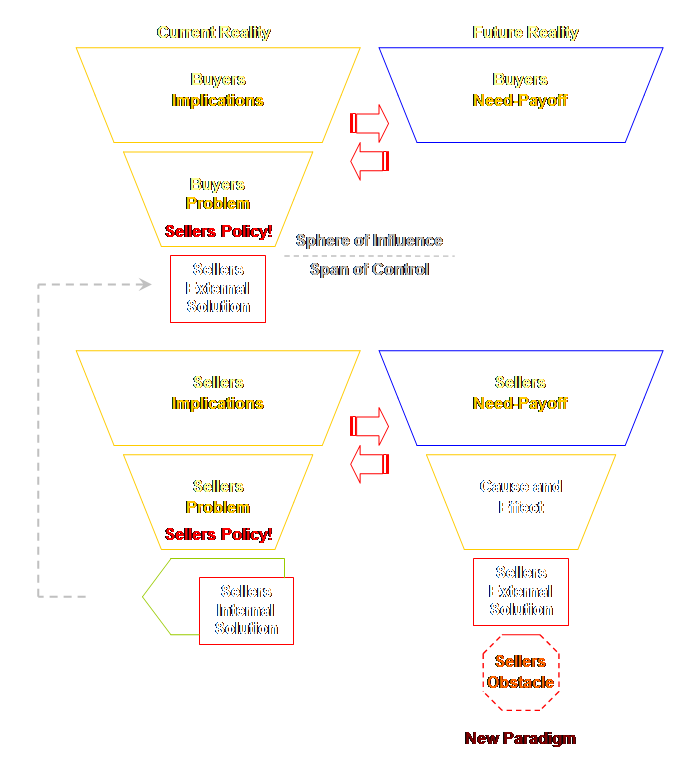

This is where the Mafia Offer is much more developed

than the SPIN model, we are developing a solution and that solution may be

nothing more than an idea, or a change in behavior, or something

similar. We may not even ask for a

price for the solution itself. The

payment is via the increase in our throughput that the solution enables. But there is a deeper issue here. Most often the injections to conflicts in

the cost world come from an understanding of the throughput world. The cost world is the world of reduction

and efficiency – the paradigm of our pre-industrial past, the throughput

world in contrast is the world of systemism and subordination – the paradigm

of our industrial present. Oops – once

again we come up against changes in paradigm.

We have been there once already with the SPIN model. Unlike the SPIN model, Mafia Offers do allow detail

complexity sales across paradigms.

Maybe this is the most important aspect of the offer. This occurs because the paradigm change is

now “isolated” within the seller’s span of control. The buyer need never even know about

it. Yes, we must still make a detail

complexity sale across a paradigm, but now the process is entirely internal

within our seller’s system. Let’s have

a look.

When we need to sell detail complexity across

paradigms, this is the method to use if we don’t wish to disclose the paradigm

transfer (we don’t want to disclose the solution to our competitors) or where

transferal doesn’t seem possible. Returning to the beginning; we still need to

explicitly address the problem within the problem – how does Theory of

Constraints present a sales constraint to itself? I believe through a failure to recognize the

difference between “within paradigm” and “across paradigm” selling. We believe that we are selling solutions to

symptomatic problems or that we are selling benefits (as defined by

Rackham). Sure, people understand and

agree with the benefits being sold and with the value to be gained versus the

price being proposed. The problem is

that – like the insufficiency reservation earlier – the buyer is trying to

make the cause and effect connection back to the sellers solution and can’t. The

buyer can’t make that connection because the agreed to and desired benefits

are expressed in one paradigm, whereas the seller’s solution is founded in

another paradigm. Even if we don’t

make this explicit, the buyer senses it. We too often mistakenly believe that “if only people

would understand the detail of the solution they will also understand the

underlying paradigm” – dead wrong. If

people understand the paradigm first – if the paradigm is transferred

properly – then people can, and do, understand the detail – but not

before. Before they will only

interpret the proposed detail in terms of their current paradigm. We have to ensure transferal of the paradigm first

if we are to stop ourselves from forcing our clients to abandon the transaction. It’s not possible to do justice to the richness of

either of the SPIN methodology or to Mafia Offers on this page. The aim, however, was to place both of them

within the broader context of the Theory of Constraints in general and

paradigms in particular. Once again a recurring theme is that we must

transfer the paradigm first – the underlying dynamics, and ensure that this is

understood before we attempt to show the subsequent detail or the outcome of

the solution. The only alternative is

the “quarantine” the paradigm within the seller’s domain. (1) Rackham,

N., (1988) SPIN selling. McGraw-Hill

Inc., pp 5-11, 51, 57-59, 91-93, 89-90, 78-79. (2) Nonaka,

I., and Takeuchi, H., (1995) The knowledge-creating company: how Japanese

companies create the dynamics of innovation.

Oxford University Press, pg 234. (3) Goldratt,

E. M., (1994) It’s not luck. The North

River Press, Chapters 19-22. (4) Hoefsmit,

P., (1995) The “offer” doesn’t always work.

Video JPS-16, Goldratt Institute. (5) Hoefsmit,

P., (1996) A Mafia Offer isn’t enough.

Video JCS-5, Goldratt Institute. This Webpage

Copyright © 2004-2009 by Dr K. J. Youngman |