|

A Guide to Implementing the Theory of

Constraints (TOC) |

|||||

Please

note. This is an older page that has been

superseded by one called Evaluating Change. This

older page remains on-line because it is still referenced by other pages. Financial Navigation Imagine for a moment that you are a passenger on a

plane with a competent pilot, but with a slightly dysfunctional navigation

system. Sometimes the navigation

system guides you to your chosen destination, but sometimes it does not. Maybe that is alright for fair-weather

flying when our competent pilot can use some visual reality checks, but is

that good enough for all-weather flying? In a way, management accounting in its current form

is like a slightly dysfunctional navigation system. Sometimes it guides us to the right

destination, sometimes it doesn’t – and it is at exactly that time that we

depend upon the experience and intuition of the management to do the reality

checks. Certainly this is not an ideal

system. What if we aren’t in a

fair-weather situation? What if the

management believes implicitly in the authenticity of the accounting

guidance? However, there is a deeper issue here. Why do we use accounting as the guidance

system at all? We saw in the previous

pages that operations managers already have a systemic and systematic method

of evaluating decisions and choosing the correct one to guide us in our

chosen direction. Why then does

accounting second guess these decisions?

The reality seems to be that we accept that accountants should not

only measure and report the financial results; but that they should also make

and measure the individual management decisions along the way that are the

perceived drivers of the financial results.

If we are going to insist on this, then let’s make sure that we provide

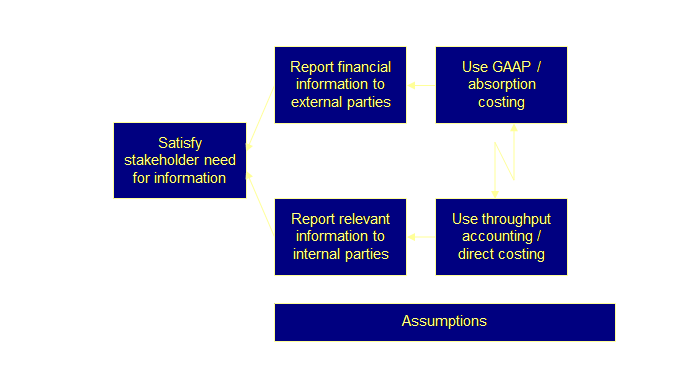

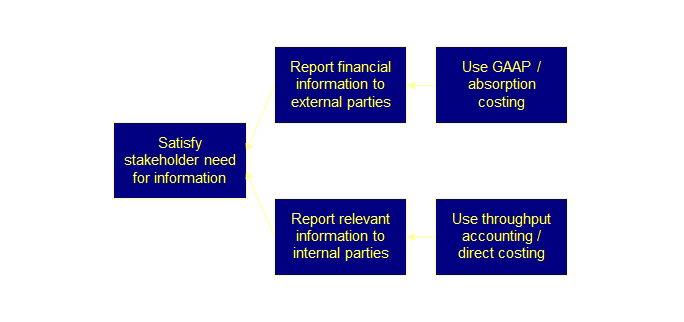

everyone with the right tools for the right job. It is apparent then that there are two jobs that

accounting wishes to perform; (1) Financial Accounting – external

reporting to regulatory authorities (the Government). (2) Management Accounting – internal

reporting to superiors (the boss). And for these two jobs there are currently two

toolsets; (1) Absorption costing –

product/process cost (2) Variable costing – product/process

contribution. Financial accounting is governed at national and

sometimes international levels by a code of generally accepted accounting

practice (GAAP). In fact the Japanese

have a term for this – generally accepted U.S. accounting practice! GAAP is absorption and accrual based. Even if some of the assumptions and methods

are arbitrary and historical, GAAP presents a consistent and level playing

field. Management accounting however is more variable. Historically, it is governed by the concept

of absorption costing – a direct transfer of financial accounting practices

into management accounting. Here

decisions are based upon a construct called the “product cost.” However there are variations that are

direct or variable costing based. Here

decisions are based upon a construct called the “product contribution.” We can more realistically know the product

contribution than we can the product cost.

We have used product contribution in the measurements section to guide

our decisions, this we might think of as throughput decision analysis. If we extend these concepts to a management

accounting level then and call this throughput accounting then at “a

conceptual level, throughput accounting is indistinguishable from

contribution margin” and “at the conceptual level there is no difference

between throughput accounting and variable costing (1).” At an accounting level throughput accounting is a

cash-based non-allocation method. It

is conservative in revenue generation (as sale isn’t a sale until it is

sold), raw material is valued at it purchase value. A sale means a sale to outside of the

system, in this day and age of supply chain management means channel stuffing

is still accepted practice in many places.

Therefore throughput accounting is similar to a small business

cash-based accounting system. “The basic difference between throughput accounting

and full-absorption accounting is the treatment of fixed manufacturing

overhead expenses. Throughput

accounting expenses overhead in the period the product is produced (i.e.

current period expense) vs. full-absorption, which assigns overhead to the

product to be carried as part of the inventory valuation until the period the

product is sold (I.e. expensed as cost of sales when the product is sold

(2). As a cash-based accounting

system, throughput accounting can be reconciled to full-absorption based

accounts at period end (2). Direct labor unless it is contract or piece-rate is

not considered to be a variable cost, but is instead a part of operating

expense. The rationale for this is

explained in detail later in this section. The ultimate difference between throughput

accounting and other less extreme forms of variable costing is that local

decisions are based upon the role of the constraints and the relative and

absolute contribution due to the constraints. It is a kind of “horses for courses” situation. If GAAP was used exclusively for financial

accounting (because we have no choice) and throughput decision analysis was

used exclusively for management accounting there would be no problem. However, this isn’t the way the world works

at the moment (apart from some particularly effective companies). Generally, absorption costing is used for

both financial accounting and management accounting. If we know that absorption costing is relatively

slow and sometimes leads to the wrong management decisions, and we know that

throughput decision analysis is quick and effective and so far has never

given rise to an incorrect decision, then why don’t we use throughput

accounting? We know that we must use

GAAP for external reporting – we have no choice. But does this mean we can’t use throughput

decision analysis for internal decision making? In fact; “... no matter what costing method a company uses,

at the end of the year you will have the same cash, assets, liabilities,

workforce, and market. But, the method

you use will lead you to very different (and opposite) strategic

decisions. If the

decisions are opposite, then only one of them can be optimal, and it is

dependent on the company-specific environment, the environment reflected by

the company’s constraint (4).” Let’s investigate this further. Debra Smith presents this as a cloud (4). It’s redrawn here.

Our cloud will now look like this;

There seems to be two answers to this; (1) Most people are unaware of the

pivotal role of constraints. (2) A strong pre-existing belief that

financial accounting is management accounting. We then are in a much better position, we are aware

of the pivotal role of constraints and we aware that absorption-based costing

does not always lead us to making correct decisions. Let’s have a look then at throughput accounting and

then, later, a brief look at a more recent development – constraints

accounting. Businesses have two choices. Firstly they could keep all accounts as

throughput accounts and converting to GAAP accounts for financial reporting at

period end. That way all decision

analysis is throughput based and two sets of accounts don’t have to be

kept. Smith details a procedure for

the reconciliation of throughput accounting to full-absorption accounting at

period end (2). This is likely to

appeal to smaller businesses.

Secondly, larger businesses with a full GAAP financial accounting

system will mostly likely want to run a throughput accounting decision

analysis system along side the financial system and not use the management

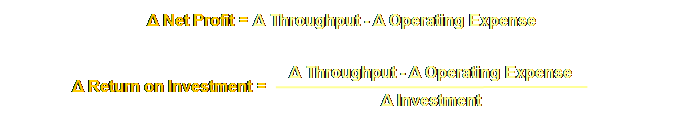

information derived from the financial accounting system. In the measurements section we introduced and

developed the concept of throughput (T), inventory (I) and operating expense

(OE) as the fundamental operational measures.

With knowledge of the role of the constraints we can use these

measures to drive maximal process profitability if that is our goal. In comparing a decision – either between different

potential outcomes, or the current situation and different potential outcomes

– we are doing so against the bottom line measures that we first saw in the

measurements section. Here, however,

we are interested in the differential generated.

Of course we can only determine the throughput

necessary for these decisions by knowing the volume and the rate at which

throughput is generated per unit of scarce resource. Let’s call this T/cu. And to know this, of course, we must know

where the constraints are. In fact we had the opportunity to experience all of

the throughput decisions as we worked through the answers to the P & Q

analysis in the measurements section.

Schragenheim and Dettmer summarized the decisions and actions required

as a flow diagram (5). Let’s distil

this down to just two rules. Whenever we make a decision we must evaluate the

consequences based upon where the constraint is now (internal or external)

and where it will be next (same place or another place). We can summarize this as two basic rules; Rule 1: when a constraint is

internal we must evaluate the throughput generated per unit time on the

constraint (T/cu). If a new product is introduced on an existing

constraint we must calculate the new T/cu and reprioritize the sequence of

all other products produced on the constraint. If the constraint moves internally we must

recalculate the T/cu for all the products produced on the constraint. If the constraint moves externally then

rule 2 applies. Rule 2: when a constraint is

external any throughput above totally variable cost is a positive

contribution to the system. Adding new products in this case has no effect so long

as they don’t cause the constraint to shift internally. If they do rule 1 applies again. Why must we do this each time? “You see, in the ‘cost world’ almost

everything is important, thus changing one or two things doesn’t change the

total picture much. But this is not

the case in the ‘throughput world.’

Here, very few things are really important. Change one important thing and you must

re-evaluate the entire situation (6).” “We have to evaluate the impact, not of a product,

but of a decision. This evaluation

must be done through the impact on the system’s constraints. That’s why identifying the constraints is

always the first step (7).” The case where the constraint remains internal to

the process is straightforward.

However if the constraint is in the market or moves to the market then

a new logic emerges. Essentially any

additional revenue that exceeds total variable cost makes a contribution to

increased profit. However, in general,

firms don’t chase such small margins.

There are two reasons for this.

Firstly, we don’t want to start a price war within our existing

market, and secondly many of our other potential markets are not sufficiently

segmented or we don’t know how to properly segment them to stop a price war

“leaking” over to our existing market. We mentioned that we must also consider total

volume. Just as we would have liked

only business class passengers to fill our aircraft in the example in the

measurements section, we know that isn’t going to happen. We are quite happy to fill most of the

aircraft with economy class passengers because overall they make a

substantial contribution – it’s just that it is not the best contribution

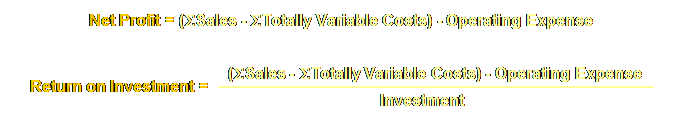

possible. So, we are really making decisions based more like

this; Throughput = SSales - STotally Variable Costs

Here is the table we used to present such data. Thus we can see the location of the

constraints (Q and Q’ are market constrained, P and P’ are resource

constrained), throughput and volumes.

Of course much of the data for the non-constraints

in reality is redundant. We only need accurate

data for the constraint and any emergent constraints. Buffer management should tell us where the

emergent constraints are. The only

thing missing from this table is our measure of T/cu. Let’s add that for completion.

In fact this format is particularly well suited for

using with “Solver,” the Excel add-in module for linear programming. If you would like to see how to assign

cells for this particular example using solver, please have a look here. In the P & Q analysis we didn’t calculate the

return on investment between different decisions; however, there are a series

of pro-forma examples allowing for sales mix, additional operating expense,

and investment that can be used to make these evaluations (10). Familiarity with these will allow you to

tackle all throughput decisions. We saw that decision analysis revolves around two

questions;

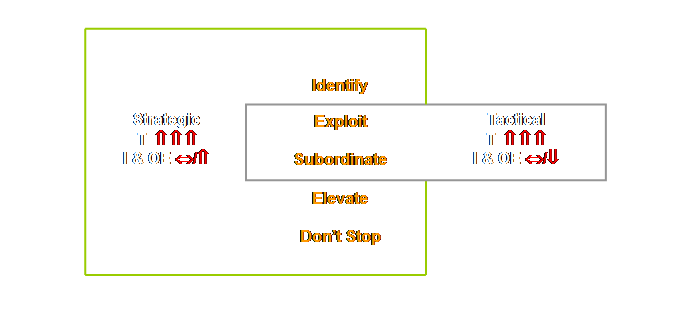

Now that we are also explicitly aware of the 5

focusing steps, we can place these decision analyses in a broader framework

of strategic or tactical significance (11).

When we elevate a constraint we must bring

additional investment into the system, usually the purchase of additional

capacity. We may also need to increase

operating expense in order to utilize the new capacity. Thus inventory (investment) will increase

and operating expense will most likely increase also, if only due to the

increased depreciation of the new investment. This brings us to an interesting point concerning

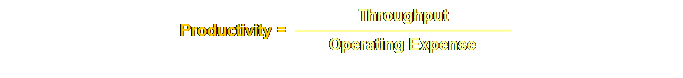

our definition of productivity;

(1) Fulfilling a necessary condition. (2) Increasing throughput. In the first instance there might be a case for

discount rate based upon economic life.

However, in the second instance we are making an investment on the basis

that income will jump and payback will be quick. We expect rapid and substantial increases

in throughput and hence should be able to convert the investment to operating

expense at a commensurate rate.

Constraints accounting addresses this more fully that throughput

accounting. Neither tactical nor strategic decisions should be

passive – determined by the next accidental emergence of a new

constraint. They should be the result

of active analysis of where we want the constraint to be. After all, the location of the constraint

dictates the way in which our firm will make money – and where our capital

investment, product development, marketing and sales efforts will be. The subdivision of whether something is tactical and

strategic based upon external investment is useful, but often substantial

improvement can be obtained without additional investment at all. In fact during this tactical phase

questions of strategic importance can occur.

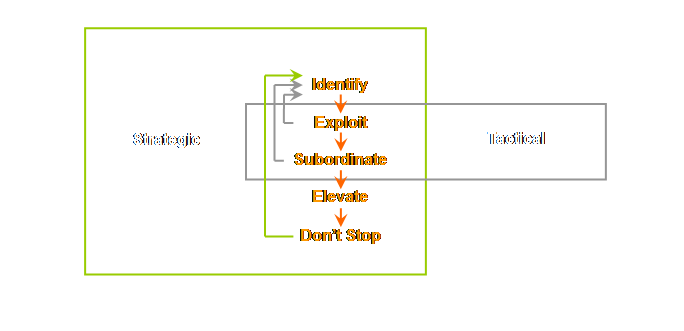

So, let’s not be mislead into believing that constraints are only

broken by elevation, often, especially in the early stages of an

implementation, proper exploitation may be all that is required to break a

constraint and move the new constraint somewhere else in the system. Let’s draw this

We can also break an apparent constraint simply by

proper subordination. Consider in manufacturing

where non-constraints may be regrouping separately scheduled process batches

together again – insubordination (pun intended). This will actually slow the whole process

down and if it occurs in one area – maybe near the gating operation for instance

then it may appear as an apparent physical constraint somewhere else. The other extreme might be when sprint

capacity is beginning to be eroded due to increased output, constraints will

appear to be “breaking out” in various places – however the solution is to

increase the buffer size. Really the constraint in both cases is in the

inertia of our subordination policies.

We can “short” the loop once again; identify-exploit-subordinate-identify. So we don’t have to go through the process

in a linear fashion from start to end, reality is far more messy and

interesting than that. We can break a

constraint at any point, and then we must go back to the first step and

identify where the constraint has moved to (but usually it is fairly

obvious). In fact normally buffer

management will have warned us where the emergent constraints are likely to

be. If the location of the constraint dictates the way

in which our firm will make money or our organization will make output, we

may in fact have a preferred place for the constraint to be. It may remain in the same place for long

periods of time; both static and strategic.

Too often we are confused by the notion that bottlenecks “wander” or

“pop up.” We can control the process

if we want to – that is what buffer management allows us to do. The premier example of wandering bottlenecks must be

winter respiratory admissions to hospitals.

Every year almost without fail, batches of patients besiege public

hospitals. It isn’t the bottlenecks

that wander (capacity constraints) it is the large batches of patients that

wander. If you can imagine a cartoon

of a python having eaten a rodent you will understand wandering bottlenecks. And every year without fail hospitals don’t

load-balance non-medical non-acute procedures to accommodate these waves (you

don’t understand we are not manufacturing we are different). In fairness more recently public health

officials have learnt that a free flu vaccination subordinates the batch size

to the constraint and lowers the overall cost. In fairness also, public health monitoring

of general practitioners offers a kind of buffer management of impending

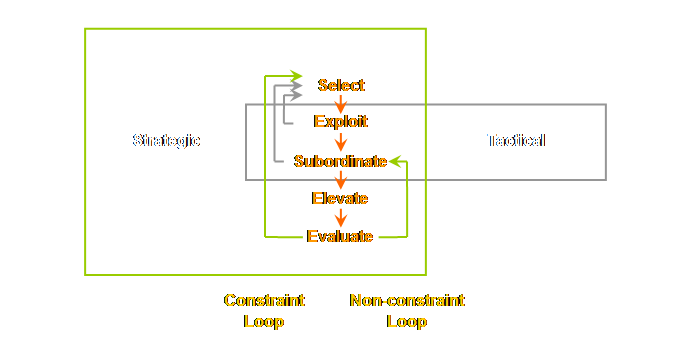

holes in the buffer. We saw on the process of change page how the

focusing process can be reworded to accommodate this strategic perspective

(12). (1) Select the leverage points. (2) Exploit the leverage points. (3) Subordinate everything else

to the above decision. (4) Elevate the leverage points. (5) Before making any significant

changes, Evaluate whether the leverage

points will and should stay the same. The key words here are; select

and evaluate. We select where we would like the strategic

constraint to be, if not now then sometime in the future, and we then

evaluate our exploitation procedures against this decision. This strategic view requires a more focused approach

to non-constraints and near-capacity constraints. Near-capacity resources must be removed

(12), therefore we must; (1) Identify near-capacity

constraints. (2) Evaluate their significance. (3) If necessary, remove their impact. Essential this is a type of “subroutine” loop for

near-capacity constraints running within the subordination step above. In practice this means that some current

non-constraints and all current near-capacity constraints must be evaluated

and steps taken to ensure that they can continue to correctly subordinate to

the strategic constraint. If demand or

product mix changes so that they have insufficient protective capacity then

they must be elevated prior to the elevation of the strategic constraint and

elevated sufficiently at that time relative to the future capacity of the

strategic constraint that they do not inadvertently become the constraint

themselves. The identification of

near-capacity constraints is a function of buffer management. The identification of the strategy and

strategic constraint is the function of the leadership. Let’s modify our diagram to reflect this more

strategic view.

The strategic nature of the 5 focusing steps – our

plan of attack – is important. If you

are especially comfortable with this concept, or more so if you are

especially uncomfortable with this concept, then click here for an extended discussion. In determining a desired future strategic constraint

we may come up against a small dilemma.

It is expressed at two levels. (1) We must subordinate a current

tactical constraint to a future strategic constraint. Consider for example a tactical constraint that is

the paint booth in a small engineering shop, and we want the constraint to

eventually move to the assembly area of that shop. In order to do so, we may have to forgo

maximum financial throughput per unit time on the current tactical constraint

in order to build the correct business for the future desired financial

throughput on the chosen strategic constraint. We can step this up to the next level. (2) We must subordinate a current strategic constraint to a future

strategic constraint. Imagine for example a successful regional airline

that decides to change market focus from short-haul and build its long-haul

traffic. In fact, we don’t need to

imagine examples. We can see exactly

this in Toyota today as that company develops hybrid engine technology and

brings it to market ahead of perceived demand (15). The development of the Cummins Engine

Company and the philosophy of the Irwin-Sweeny-Miller families is another

exceptional example of this process (16).

Both of these firms are examples of leveraging on the present to

create the future. The leveraging

results in lower current profit than would otherwise be possible – and a

greater future (and total) profit than would otherwise be possible. In fact we could step back a little to contemplate

how Toyoda Spinning and Weaving – a very successful firm in its own right

evolved into an auto manufacturer. If

this is too recent and singular then we are reminded that Mitsui was once a

drapery shop, then money lender, then a mining and manufacturing enterprise –

originating in the mid-1600’s. Sumitomo started out in 1590 as a copper

casting shop, then moved into trading, and then mining, then manufacturing,

followed by banking and chemicals (17). Caspari and Caspari capture this dilemma which

occurs whenever such a new strategic constraint is selected. The dilemma is presented very nicely as a

short-run versus long-run cloud (18).

Let’s have a look at this cloud – here inverted.

Everything that we need to know to describe the

situation is there, but let’s reword this cloud slightly before we look more

closely.

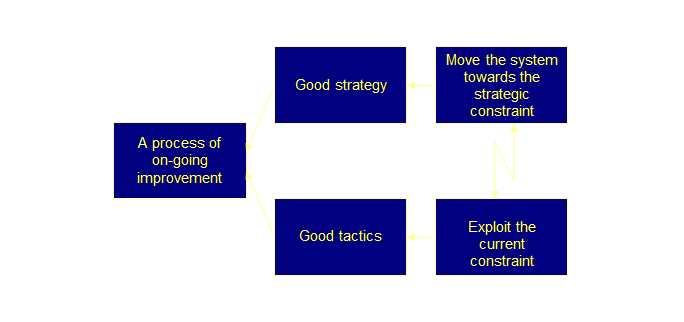

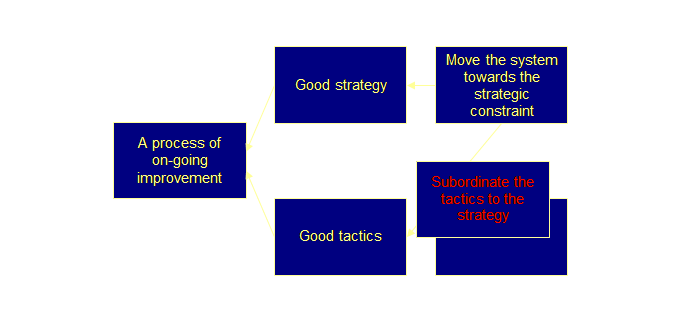

A conflict arises however from the extension of

these needs. In order to have good

tactics we must exploit the current constraint – otherwise what was the point

of having a constraint in the first place.

Also in order to have good strategy we must move the system towards

the future desired strategic constraint – otherwise our leadership decisions

will not be implemented. And herein

lies the dilemma; we can not both exploit the current constraint and not

exploit the current constraint (move the system towards the strategic

constraint). How can we break this dilemma? Let’s see.

In fact, if we substitute “long-run” for “good

strategy” and “short-run” for “good tactics,” then I think that we can see a

generic cloud that covers many more system and personal situations than just

this one. All firms will have a set of GAAP financial

statements. These will allow you to

have quick look at the health of the system.

In order to do so we need to rearrange the numbers as per the

following table.

Sales commissions become a part of totally variable expenses,

manufacturing variable and fixed overhead becomes an operational

expense. Direct labor becomes an

operational expense. Inventory is

valued at the raw material value and operational expenses are increased by

the portion previously “allocated” to stock. Every entry in the absorption costing is also

represented in the throughput costing and the net result is the same. However, now we can see at a glance whether

we are making a profit – does throughput exceed operational expenses – is our

operating income positive. Of course

this doesn’t allow us to drill down to the drivers, to do that we would need

knowledge of the location of the constraints. Such a quick conversion also allows us to evaluate

the consequences of increases in throughput and decreases in pricing. Goldratt’s consistent admonishment is not

to decrease prices (19). However, it

certainly happens and it often happens without consideration for the amount

of increased sales necessary to maintain the pre-existing equilibrium (“the

market demanded it”). It also happens

without consideration for the other non-price penalties the firm already

inflicts upon its market – late orders, long lead times, poor product

quality, and frequent out of stock for example. We will examine these a little more in the

section on supply chain. Increasing productivity in a healthy business will,

as we saw in the section on bottom line, increase profitability

substantially. The ensuring robust

cash flow should allow the business to grow even further. But what of companies that are not so

healthy to begin with, maybe companies that are at the other end of the

spectrum facing commercial recovery or turnaround? For such companies cash flow and perhaps

even the timing of cash flows is of critical importance. Goldratt and Fox characterize cash flow as; ”… an on-off measurement. When we have enough cash, it is not

important. When we don’t have enough

cash, nothing else is important.” Cash

flow is a survival measurement (20)! Be that as it may, there is little discussion of

cash flow within the constraint management literature (21, 22). However, Stein mentions how to use a

constraint schedule and Throughput Accounting to effectively manage cash flow

in situations where this is imperative (23). Let’s repeat the definition of cash flow from the

measurements page; Cash Flow = Throughput - Operating Expense + Inventory Change Note however, that when there are stock movements; Net Profit = Throughput - Operating Expense - Inventory Change This is especially important for absorption-based

accounts because the stock has overhead attached to it. Therefore; (1) When stock

increases, then profit increases,

but cash flow goes down. (2) When stock

decreases, then profit decreases,

but cash flow goes up. When overall inventory is small, or if overall

inventory is large but period to period changes are small these factors are

not particularly significant. However,

in the initial stages of an implementation where there might be a substantial

reduction of work-in-process or more importantly finished goods, then it is

important that this effect on the accounting position is known and understood

beforehand. In the situation of a turnaround getting old

work-in-process out the door as fast as possible it will bring much needed

cash into the system. For many people transferring the discounts and sales

commissions of absorption costing from indirect expenses to the variable

expenses of variable costing is OK, but transferring direct labor from cost

of goods sold of variable costing to operating expense of throughput

accounting is difficult to sanction. Part of this undoubtedly arises from the fact that

direct labor is the variable against which indirect costs are allocated to

products to obtain a “product cost.”

That is, unless, a more “sophisticated” approach such as activity

based costing is being used. There are two interrelated reasons why it is

essential to move direct labor to operating expense. They are; (1) Technical Considerations. (2) Philosophical Considerations. Let’s deal with the technical aspects first. Inherent in the assumptions of absorption costing

and variable costing is that direct labor is an avoidable cost. You can reduce direct labor. This may have been so in the past when

absorption costing was developed and most direct labor was on

piece-rates. Then, in fact, almost all

direct costs were indeed variable costs.

These days this is not so, and to make decisions based up this

assumption will lead to contrary results.

The damage caused by companies that “…still use the same cost

accounting and management control systems that were developed decades ago for

a competitive environment drastically different from that of today” is well

documented (24, 25). Moreover, even if direct labor could be considered

as a totally variable expense, in most western countries even if it is legal

it is neither particularly acceptable nor easy to lay-off staff. In Europe and Japan there are strong

governmental regulations and social norms that make this almost

impossible. It seems that our

accounting system is suffering from inertia. Given these technical considerations, there are also

deeper and much more important and powerful philosophical considerations. Superficially we know part of this already. Ask yourself, what would happen if you had

a successful improvement program, found some spare capacity – people – and

then laid them off? What would be the

chance of another improvement program within that organization within the

next 5 years? What about the next 10 years? And we saw ourselves in the section on

bottom line effects that improvements based upon cost reduction suffer

diminishing returns – so even if the people remaining will co-operate then “bang

per buck” gets less and less each time.

And of course people will co-operate but every problem will be

external and beyond their control. Now consider also what would happen if you raised

productivity and profitability (and we know this can be done), you now have

an open ended improvement process – peoples’ security is enhanced and their

desire to contribute is improved. This

is why one of the pivotal necessary conditions for a process of on-going

improvement is; provide employees with a secure and satisfying workplace now

and in the future. But deeper than this are some underlying

values. Jones and Dugdale consider

that in the foundation of Goldratt’s work there are humanitarian concerns

that are the moral framework for his management theories. “For Goldratt, … and other advocates of

TOC, …, the treatment of labor as a fixed cost is a moral and political

statement that pays more than mere lip-service to the interests of employees

(26).” Jones and Dugdale develop this

point further and compare and contrast Theory of Constraints with activity

based costing. They conclude that;

“ABC and TOC represent not only different socio-technical systems but also

different moral systems.” Being part of a different moral and socio-technical

system is not a liability. In fact it

is just the opposite; it is a definite strategic advantage. Hurst has also raised similar important

issues about Toyota’s just-in-time system (27). He makes a case for this to be a

substantial competitive advantage.

This is a concept that we will return to and examine in more depth in

the page on strategic advantage. The experience with job security in kaizen in

Japanese corporations is actually no different from that of Theory of

Constraints; “There is an important precondition that must be met …that the

shop floor has the ability to perform kaizen, and that no jobs will be lost

as a result of kaizen.” Moreover, “the

maintenance of this precondition is the key foundation for independent kaizen

(28).” In fact it almost becomes

circular. In order to improve we must

be secure, in order to be secure we must improve. Lean implementations in the United States

of America have also found that guarantees of job security are an important

part of the improvement process (29). Maybe Deming said all of this much more succinctly;

“Drive out fear (30).” Some people of reductionist/local optima persuasion

consider that throughput accounting has limited strategic capability. Hopefully the previous discussion on

strategic issues has helped.

Schragenheim best summarizes this situation as follows. “The TOC approach may remind people of the

marginal costing method, but the similarity is very superficial. TOC objects to any allocation of fixed

costs, but is not going to ignore them.

Moreover, TOC is system oriented

and by that a different logic emerges.

TOC looks for the marginal costs for the whole system rather than the

marginal costs associated directly with the decision at hand (31).” So it seems that the limitation is more to

do with a reductionist/local optima mind-set than a failure of the

systemic/global optimum environment in which this accounting should be

executed. Let’s use our system model once more to illustrate

this. Let’s draw the

reductionist/local optima view first.

Takashi Kawase sums up this problem best. “Paradigm shifts are not born out of

existing evaluation standards (especially not from economic calculations),

but from the pursuit of ideals and convictions. This is because it is not possible to

predict the merits and demerits of a revolutionary new process accurately

(32). However, within systemic/global optimum

practitioners there is awareness that throughput accounting is not

perfect. “The remaining hurdle is to

restate financial statement profit to best align executive strategy and

decision making with both short- and long-term results (33).” This brings us to the concept of

constraints accounting.

Caspari and Caspari are practitioners who are aware

that throughput accounting is not perfect; essentially we are trying to

evaluate a global-throughput paradigm with an existing local efficiency

costing paradigm and calling it throughput accounting. Caspari and Caspari borrow a term from computing

jargon to describe the situation; throughput accounting is a “legacy system”

firmly lodged in the cost world (34).

It appears that we must eventually replace it with something more

systemic – constraints accounting. Does this mean that the preceding discussion on

throughput accounting is invalid? No,

not at all. In fact I will argue we

needed throughput accounting to transition from absorption accounting to

constraints accounting. This doesn’t

mean that constraints accounting is derived from throughput accounting, it is

not, but we needed to go there first before we completely understood what was

missing. Let’s view this by analogy. In organic evolution, when a new need or

opportunity arises, organisms must “make do” with whatever is on hand – because

there is nothing else. A pre-existing

part is co-opted to a new function; thus we have the panda’s “thumb” – which

isn’t a thumb at all – and a multitude of similar examples (35). In business revolution then, when a new

need or opportunity arises, firms also must “make do” with whatever is on

hand – because, at first, there is nothing else. When drum-buffer-rope first appeared there

was a need for a consistent accounting approach. Variable costing was at hand and pressed

into service. Of course, organic

evolution is an entirely passive process whereas business revolution is

decidedly active. In business we can

invent totally new solutions, but first, we need to understand the problem. Throughput accounting limitations allowed

us to better understand the problem that we wanted to solve. Let’s try and capture this in a diagram.

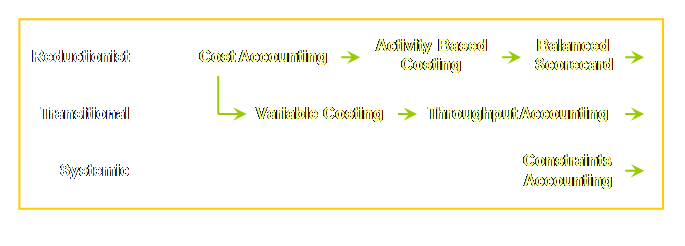

Variable costing also developed from cost

accounting, but out of the recognition that some costs are incurred

irrespective of the fixed cost component and thus better management decisions

about product cost could be made by identifying these variable or

differential costs (38). Throughput

accounting develops this concept further to the point where direct labor is

no longer considered variable.

Although product cost is avoided by instead considering throughput,

the concept isn’t very far away.

Constraints accounting is the only methodology that is truly a

systemic/global optimum approach. We saw some of the limitations of throughput

accounting in our travels through this site.

For instance we lose sight of the constraints as soon as we get above

a product level in our accounts. In

throughput accounting we make investment on the basis of a significant

increase in output or throughput then have to depreciate the investment at

some glacial rate over many years as operating expense. When the constraint moves out into the

market we don’t really know what contribution to expect from any new product,

we know that anything above material cost is a positive contribution, but

that knowledge alone isn’t sufficient.

To these examples we must add Smith’s concerns above about alignment. Constraints accounting is a global throughput

accounting paradigm with which we can evaluate our global-throughput

decisions/operations in an internally consistent manner. It brings the effect of identified

constraints to the profit and loss statement and therefore effectively

subordinates the management accounting function of the firm to the goal of

the organization in a true process of on-going improvement. It provides a bridge for building new

product contribution expectations. It

allows us to recover investment in breaking constraints as operating expense

at rates commensurate with the new rate of throughput. And it provides a means of goal congruence

via financial incentives to bust constraints, thus generating alignment for

both short-term and long-term results.

In broad principle the incentive system is not dissimilar to those

suggested for kaizen in Japan (39). Let’s hope that constraints accounting will

eventually be published. In the

meantime much of the basic material is available on-line (see links and resources). We ended the preceding section on the note that if

there is one department that can block all others then that department is

finance. We have seen, however, that

there is no need for this to occur.

Indeed financial accountants – people who deal with and understand

flows of money – will wonder what all the fuss is about. After all it’s just common sense. Let’s turn our attention then to some of the broader

aspects of leadership. (1) Noreen, E., Smith, D., and Mackey, T., (1995)

The Theory of Constraints and its implications for management

accounting. North River Press, pg 13. (2) Smith, D., (2000) The measurement nightmare: how

the theory of constraints can resolve conflicting strategies, policies, and

measures. St Lucie Press/APICS series

on constraint management, pp 107-113. (3) Smith, D., (2000) The measurement nightmare: how

the theory of constraints can resolve conflicting strategies, policies, and

measures. St. Lucie Press, pp xv &

28. (4) Smith, D., (2000) The measurement nightmare: how

the theory of constraints can resolve conflicting strategies, policies, and

measures. St. Lucie Press, pg ix. (5) Schragenheim, E., and Dettmer, H. W., (2000)

Manufacturing at warp speed: optimizing supply chain financial performance. The St. Lucie Press, pp 225-244. (6) Goldratt, E. M., (1990) The haystack syndrome: sifting

information out of the data ocean.

North River Press, pp 96-97. (7) Goldratt, E. M., (1990) The haystack syndrome: sifting

information out of the data ocean. North

River Press, pg 98. (8) Dettmer, H. W., (1998) Breaking the constraints to world class performance. ASQ Quality Press, pg 37. (9) Corbett, T., (1998) Throughput Accounting: TOC’s

management accounting system. North

River Press, pg 43. (10) Corbett, T., (1998) Throughput Accounting:

TOC’s management accounting system.

North River Press, pp 41-80. (11) Schragenheim, E., and Dettmer, H. W., (2000)

Manufacturing at warp speed: optimizing supply chain financial

performance. The St. Lucie Press, pp

56-57. (12) Newbold, R. C., (1998) Project management in

the fast lane: applying the Theory of Constraints. St. Lucie Press, pp 152-155. (13) Lepore, D., and Cohen, O., (1999) Deming and

Goldratt: the Theory of Constraints and The System of Profound Knowledge. North River Press, pp 107-112. (14) Abney, A., and Caldwell, R., (1998) It just

can’t be this simple – Valmont Industries.

Video JSA-12, Goldratt Institute. (15) Liker, J. K., (2004) The Toyota Way: 14

management principles from the world’s greatest manufacturer. McGraw-Hill, pp 71-84. (16) Cruikshank, J. L., and Sicilia, D. B., (1997)

The engine that could: 75 years of values-driven change at Cummins Engine

Company. Harvard Business School

Press, 587 pp. (17) De Geus, A., (1997) The living company: habits

for survival in a turbulent business environment. Harvard Business School Press, pp 108-111

& 144-145. (18) Caspari, J. A., and Caspari, P., (2004)

Management Dynamics: merging constraints accounting to drive

improvement. John Wiley & Sons

Inc., pp 261-262. (19) Noreen, E., Smith, D., and Mackey, T., (1995)

The Theory of Constraints and its implications for management

accounting. North River Press, pg 17. (20) Goldratt, E. M., and Fox, R. E., (1986) The

Race. North River Press, pg 20. (21) Dettmer, H. W., (1998) Breaking the constraints

to world class performance. ASQ

Quality Press, pg 33. (22) Smith, D., (2000) The measurement nightmare:

how the theory of constraints can resolve conflicting strategies, policies,

and measures. St. Lucie Press, pg 48. (23) Stein, R. E., (1996) Re-engineering the

manufacturing system: applying the theory of constraints (TOC). Marcel Dekker, pg 181. (24) Kaplan, R. S., (1984) Yesterday’s accounting

undermines production. Harvard

Business Review, Jul-Aug, pp 95-101. (25) Johnson, H. T., and Kaplan, R. S., (1987)

Relevance lost: the rise and fall of management accounting. Harvard Business School Press, 296 pp. (26) Jones, T. C., and Dugdale, D., (2000) The

making of "new" management accounting: a comparative analysis of

ABC and TOC. Proceedings of the Sixth

Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Accounting Conference, Manchester, U.K.,

July, pp 20-21. (27) Hurst, D. K., (1995) Crisis & renewal: meeting the challenge of organizational change. Harvard Business School Press, 228 pp. (28) Kawase, T., (2001) Human-centered

problem-solving: the management of improvements. Asian Productivity Organization, pp

118-119. (29) Womack, J. P., and Jones, D. T., (1996) Lean

thinking: banish waste and create wealth in your corporation. Simon &

Schuster, pp 139-140. (30) Deming, W. E., (1982) Out of the crisis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

Centre for Advanced Education, pg 59. (31) Ptak, C. A., with Schragenheim, E., (2000) ERP:

tools, techniques, and applications for integrating the supply chain. St. Lucie Press, pp 28-29. (32) Kawase, T., (2001) Human-centered

problem-solving: the management of improvements. Asian Productivity Organization, pg 179. (33) Smith, D., (2000) The measurement nightmare:

how the theory of constraints can resolve conflicting strategies, policies,

and measures. St. Lucie Press, pg 131. (34) Caspari, J. A., and Caspari, P., (2004)

Management Dynamics: merging constraints accounting to drive

improvement. John Wiley & Sons

Inc., pg 45. (35) Gould, S. J., (1980) The Panda’s thumb: more

reflections in natural history.

Penguin, pp 19-25. (36) Kaplan, R.S., and Norton, D.P., (1996) The

balanced scorecard: translating strategy into action. Harvard Business School Press, 322 pp. (37) Smith, D., (2000) The measurement nightmare:

how the theory of constraints can resolve conflicting strategies, policies,

and measures. St. Lucie Press, pg

136-137. (38) Johnson, H. T., and Kaplan, R. S., (1987)

Relevance lost: the rise and fall of management accounting. Harvard Business School Press, pp 153-158. (39) Kawase, T., (2001) Human-centered

problem-solving: the management of improvements. Asian Productivity Organization, pg

111-119. This Webpage Copyright © 2003-2006 by Dr K. J.

Youngman |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||