|

A Guide to Implementing the Theory of

Constraints (TOC) |

|||||

The Five Focusing Steps – Structured and

Strategic Concepts, just like sports cars or fighter planes,

are often at their leanest, fastest, and greatest maneuverability in their

earliest form. Later on they often

acquire additional bits and pieces that increases their functionality but at

the expense of the initial specification.

The original verbalization of the 5 focusing steps by Goldratt is a

little like the earliest form of a fast and agile sports car. The original verbalization is perfectly

adequate and it should be the one that we refer to most often. There are many people who are quick to

recognize both the tactical and strategic implications of this concept. There are however two more recent re-verbalizations

of the basic 5 focusing steps that suggests that maybe some people have

trouble in initially “seeing” the tactical and strategical duality. Rather than looking past the more immediate

tactical issues to the strategic drivers, they tend to focus and become

“stuck” on the immediate, but overall less important, tactical implications. The 5 focusing steps are without doubt structured

and tactical; but more importantly they are also strategic in intent. Let’s review Goldratt’s original

verbalization and then the subsequent re-verbalizations and see if we can

come to a better understanding of the strategic intent inherent in this

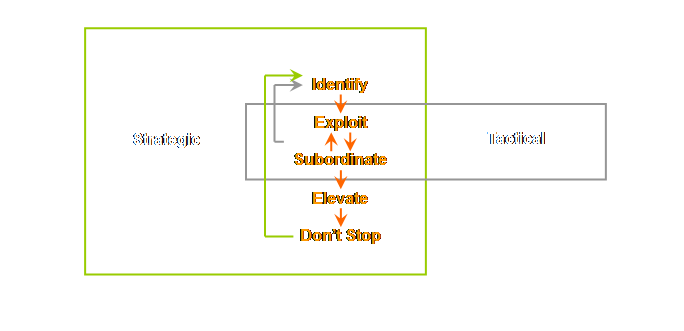

process. Goldratt’s earliest published verbalization of the

five focusing steps is as follows (1); (1) Identify the system’s constraints. (2) Decide how to Exploit the system’s constraints. (3) Subordinate everything else to the above decision. (4) Elevate the system’s constraints. (5) If in the previous steps a

constraint has been broken Go back to step 1, but do not allow

inertia to cause a system constraint. We drew a slight modification of this verbalization

on the Process of Change page replacing “go back” with “don’t stop” and

adding a plural to step 3, to arrive at the following; (1) Identify the system’s constraints. (2) Decide how to Exploit the system’s constraints. (3) Subordinate everything else

to the above decisions. (4) Elevate the system’s constraints. (5) If in the previous steps a

constraint has been broken Go back to step 1, but do not allow

inertia to cause a system constraint.

In other words; Don’t Stop We called the 5 focusing steps or the focusing process

our “plan of attack.” Then on the

Evaluating Change page we started to “subdivide” the process into strategic

and tactical aspects. Lets redraw the diagram that we produced.

There are however two messages inherent in the

discussion on the focusing process on the Evaluating Change page. The first message is that some tactical

issues are so simple and so cheap that we should just go out and do them

immediately. The change that is

brought about by this exploitation is often large as well as very rapid. The second message is that even while we are

acting upon these easy leverage points, we should also have in mind where we

would like the constraints to reside once the system has “settled” down –

once the system has been through a couple of iterations of

exploit-subordinate-elevate. In other

words; how can we design the system to maximize the goal of the system. This brings

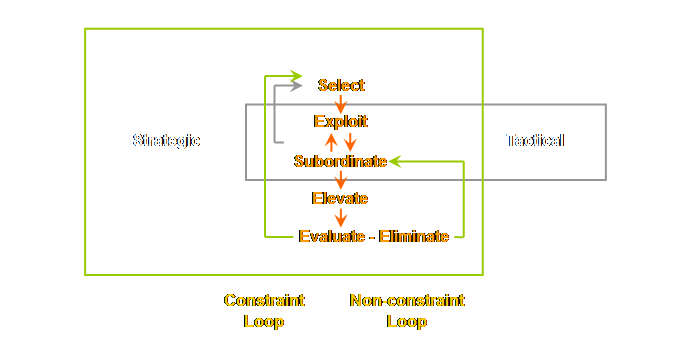

us to the first re-verbalization. Robert Newbold offered a re-verbalization of the 5

focusing steps that firstly recasts the constraints as leverage points, and

secondly better explains the strategic nature (2); (1) Select the leverage point(s). (2) Exploit the leverage point(s). (3) Subordinate everything else to the above decisions. (4) Elevate the leverage point(s). (5) Before making any significant

changes, Evaluate whether the leverage

point(s) will and should stay the same. Newbold argues; “We want to be proactive in

controlling where the leverage points are and where the focus of the

organization is. This doesn’t mean we

stop improving; it means we control the improvement process much better. The implications of this change are

far-reaching. Since the leverage

points have been selected on a strategic basis, any temporary constraints

that arise must be eliminated as a matter of policy. There must be a new organizational policy

that reads as follows: Identify, evaluate and,

most likely, eliminate any constraints that have not been selected.” This approach of evaluate and eliminate any

constraints that have not been selected as the strategic constraint is

essentially a subroutine to ensure adequate subordination of potentially

emergent near-capacity constraints; subordinated that is, with respect to the

selected strategic constraint. We can draw a model of this verbalization as

follows;

Let’s digress for a moment into the semantics of

this situation. We can’t by definition

exploit a non-constraint, so Newbold’s choice of eliminate is apt. If we left a non-constraint or a

near-capacity constraint long enough that it impinged upon the strategic

constraint, then it would indeed become the constraint for a short period and

we could exploit or better still elevate it until is was once more

subordinate to the strategic constraint.

Of course we don’t want this situation to arise and so we must

proactively elevate the incipient near-capacity constraint or non-constraint

and ensure continued subordination.

Thus evaluate and eliminate expresses this subordination loop well. Newbold’s verbalization makes the strategic

intent explicit. However, there is

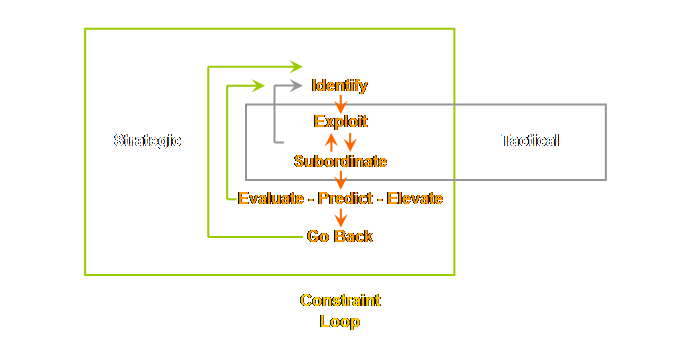

another more recent attempt, lets look at this next. More recently Schragenheim has also offered a

re-verbalization of the 5 focusing steps in order to make its strategic

nature more explicit (3). We swap back

from “leverage points” to “constraints.”

The verbalization is a follows; (1) Identify the system's constraints. (2) If a constraint can be immediately

removed without large investments, do it now and go back to Step 1. If not, devise a way to Exploit the system's constraints. (3) Subordinate everything else to the above decisions. (4) Evaluate alternative ways to elevate one or more of the

constraints. Predict the future constraints and their impact on the

global performance by theoretically employing the first 3 steps. Execute the way you have chosen to Elevate the current

constraints. (5) Go back to Step 1.

The actual constraints may be different from what you expected ‑

beware of inertia in the identification of the constraints. As Schragenheim explains; “Step 4 has been expanded

to express its strategic meaning.

Without this expanded definition, TOC can be easily regarded as a

tactical managerial approach rather than a long-term, strategic approach.” Let’s try and redraw our model according to

Schragenheim’s verbalization.

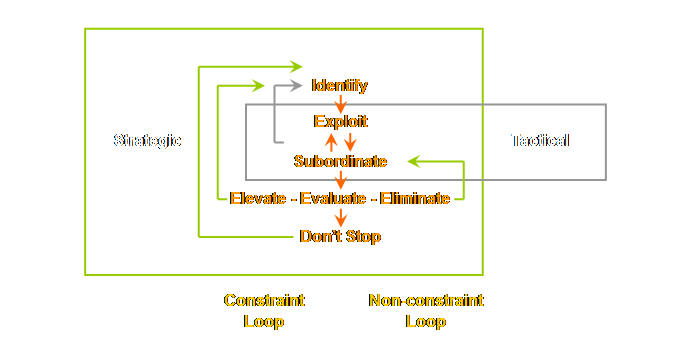

Both of the more recent re-verbalizations supplement

the original verbalization in making the strategic intent more explicit. In addition both complement each other in

the areas that they stress. In

Newbold’s verbalization the role of the non-constraints is explicit. In Schragenheim’s verbalization the role of

the non-constraints is implicit. In

Schragenheim’s verbalization the testing of multiple potential pathways is

explicit – “predict;” in Newbold’s verbalization the existence of such choice

is more implicit – “select.” In

isolation either verbalization is more than adequate. Together they are much more powerful. What to do then?

Newbold has put forth an important consideration in the development of

strategic constraints – ensuring near-capacity constraints and

non-constraints do not unintentionally become the constraint. We know how to guard against this using

buffer management. Buffer management

allows us to ensure the elimination of potential near-capacity constraints

and that they remain subordinated to the strategic constraint by timely and

appropriate action and maybe expenditure. On the other hand Schragenheim has also expressed

the same notion but in terms of the constraints only. And certainly the 5 focusing steps is a

constraint-based focusing process.

There seem to be elements from both verbalizations that are

desirable. Well, the temptation is too

great. We have a simple and robust

model to work with. Let’s try and

synthesize both Newbold and Schragenheim’s approaches into one. Let’s see what we can come up with.

The important points to remember are that we can break

constraints early on and at low or no additional expenditure, and also later

on as a consequence of considered analysis and maybe capital expenditure as

well. We must remember also to

simultaneously consider both the chosen or potential strategic constraint and

all of the actual and potential near-capacity non-constraints which we don’t

wish to become constraints. We need to recognize that implicit in Goldratt’s

original verbalization is a level of detail that makes the 5 focusing steps

not just tactical but absolutely strategic as well. The two more recent re-verbalizations are

attempts to illustrate and explain this detail and to ensure that an a priori view of the process as tactical does not become

an obstacle to further learning. Page back up to Goldratt’s verbalization. Consider that “identify” means elements of

both identify and select – passive and active. Consider that “exploit” and “subordinate”

can contain both short-term (immediate) cash-less decisions and longer term

(non-immediate) cash-required decisions. More importantly consider that the 4th step

“elevate” contains a special richness.

There are two looping structures that we can invoke here; one is

almost passive and the other is active.

The active loop is the constraint loop; early on the constraints will

“present” themselves in rapid succession, but later on we can make a

considered decision – a strategic choice – about where we wish it to be. We do this based upon our desire to move

the system towards the goal of the system.

Consider then that “elevate” means also “evaluate” and “predict” as

well. We evaluate a number of possible

pathways and predict the future outcomes before selecting a single pathway to

elevate and follow. The passive loop is the non-constraint loop. It is passive in the sense that once a

strategic constraint has been selected – either recently or in the distant

past – then the maintenance of non-constraint sprint capacity and therefore

sufficient subordination is the major concern. So, once again, we must evaluate and

predict – this time for the non-constraints. Of course the world is messy and we are massively

parallel in our thinking so all of this occurs mixed up in execution. (1) Goldratt, E. M., (1990) What is this thing

called Theory of Constraints and how should it be implemented? North River Press, pp 3-21. (2) Newbold, R. C., (1998) Project management in the

fast lane: applying the Theory of Constraints. St. Lucie Press, pp 147-155. (3) Schragenheim, E., (1999) Management dilemmas:

the Theory of Constraints approach to problem identification and

solutions. St. Lucie Press, pp 5-7. This Webpage Copyright © 2003-2009 by Dr K. J.

Youngman |