|

A Guide to Implementing the Theory of

Constraints (TOC) |

|||||

|

Multi-Project Drums |

|

|

|

Comparing

Safety In Production & Projects There are two

groups of people who are likely to use these pages on projects; those with

prior knowledge of production operations (manufacturing) and those with pure

project backgrounds. For this reason I

want to compare and contrast between production operations and project

operations. The similarities are much

greater than the differences. I want

to do this for two reasons; 1. Provide a bridge for people with production operation experience in

order to enter into the project domain. 2. Show people with project operation experience that the challenges that

they face are not that different from those experienced in production

environments. So I ask for

your indulgence if you already feel slighted that “your” area of expertise is

apparently no more difficult than “their” area of expertise. You see, we are basically all in the same

boat – and we are all at sea as well.

Industrialization is new. We only have to

check whether our parents’ generation ran projects or production operations

as we do, and if they did, then check out our grand-parents generation. The scale and scope of operations today is

vastly different from that of just one or two generations ago. For instance, just one generation ago we

didn’t have computers to make mistakes quite as quickly as we are able to

today. In fact,

computers are now so ubiquitous that we can discuss operations in terms of

the software that drives them, or at least the generic approaches. For production operations the first

software was material requirements planning (mrp or small mrp – referring to

the use of lower case letters).

Material requirements planning allowed the building of bills of

material (BOMs) for a process; a list of all the bits and pieces and maybe

the places where, and the time when, they were required. It wasn’t long before this was beefed up to

materials resources planning (MRP or MRP II) with the addition of capacity

scheduling of each step in the routing that had been used to generate the

bill of materials. More recently this

has been beefed up once again to enterprise resources planning (ERP) where

schedules are wired across functions as well as within functions. Sales and marketing now know what

production is doing and vice versa (well it sounds good doesn’t it?) The project

operations equivalent of the mrp, MRP II, ERP, alphabet soup is Critical Path

Method, (CPM for short). Critical Path

Method tends to be associated with the Gantt charts that are used to

graphically present the relationships between tasks in a project, but it is

generated from an approach called program evaluation and review technique (or

PERT for short). In fact, as we will

soon see, program evaluation and review technique can be equally applied to

production operations as well as to projects.

Indeed, maybe PERT is responsible for the two short comings of both

MRP and CPM. Both approaches assume,

even today, that there is more capacity at each step in a production process,

or task of a project, than is actually required. Colloquially, we tend to call this

“infinite capacity” although we only mean that there is “more than

enough.” Before the advent of

computers when PERT was a manual exercise, this simplification made the

impossible possible. Also, both MRP

and CPM assume that safety is localized throughout the respective

operations. In production operations,

safety is localized in the queuing of product (work-in-process). Each queue represents a safety buffer that

allows late work to catch up to its schedule through the rearrangement of items

or “jobs” in the queue. Historically,

these types of scheduling approaches originated in so-called job shop

environments – places where machinery was likely to be grouped according to

function, rather than the flow-shops that are so much more common in all but

the smallest of facilities today. In

Critical Path Method the safety is localized not in the queue, but within

each and every task in the project. Assumptions of

infinite capacity and the localization of safety throughout the operation are

the two aspects that cause so much trouble to modern operations. We won’t address the issues of infinite

capacity assumptions until the next page on Critical Chain Project

Management, because this is an important issue of itself and is to me the

distinction between Critical Chain Project Management and Critical Path

Method. On this page we will address

the issue of localized safety in each step or each task. Essentially we are going to move from

safety that is localized, specific, and everywhere, to safety that is

general, aggregate, and located in just a few critical places. Having safety

“embedded” in each step of a production process or each task of a project

ought, at first pass, seem to be an effective solution. After all you can size each individual allocation

as required – regardless of whether it is explicit within a production

process queue, or implicit within a project task. However, a number of operational and

psychological factors contrive against us.

The operational factors are the dependent nature of serial operations

and the inherent variability that occurs within each operation. The psychological factors are varied, and

probably more important for project-based operations than production-based

operations. We will deal with the

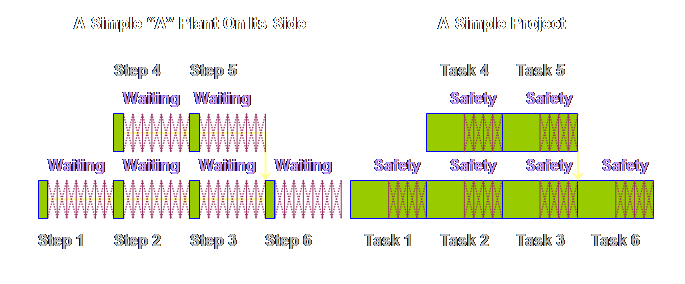

psychological factors as we come to them. In order to

develop the argument for the aggregation and placement of buffers in project

management, I am going to use a PERT diagram for both a production process

and a project. In order to do that we

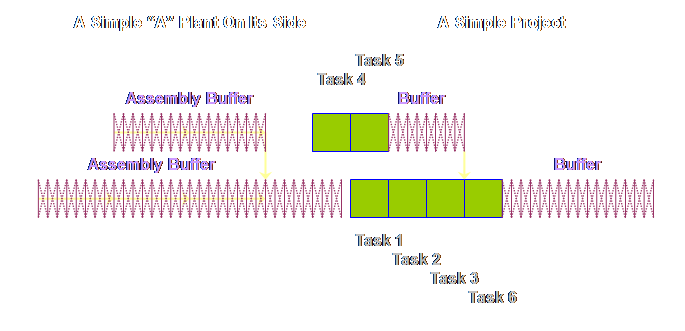

must make use of the realization that a project is an “A” plant tipped on its

side. Let’s look at

this in more detail. A project is

an “A” plant tipped on its side (1).

This is the “thing” that finally allowed me to see the relationship

between production operations and project operations and their buffers or

safety. But what is an “A” plant you

are asking? Theory of Constraints sees

4 generic flows in production operations, they are; “V” plants or divergent

plants (divergent from the bottom of the “v” to the top), “A” plants or

convergent plants (convergent from the bottom of the “a” to the top), “I”

plants or linear plants, and “T” plants – a plant with a linear stem and an

explosion of choices at the top (assembly).

Each type of plant is typical of particular operations. “A” plants are typical of situations where

a number of different components from different raw materials come together

to form a final assembly. Let’s draw a

simple, a very simple, “A” plant on its side to see how it would look.

This type of

logic diagram is common in Theory of Constraints. The logic might coincide with the physical

layout of the plant; more often than not, it won’t. For an example of a more complex “A” plant

logic diagram and its corresponding physical layout, have a look at the

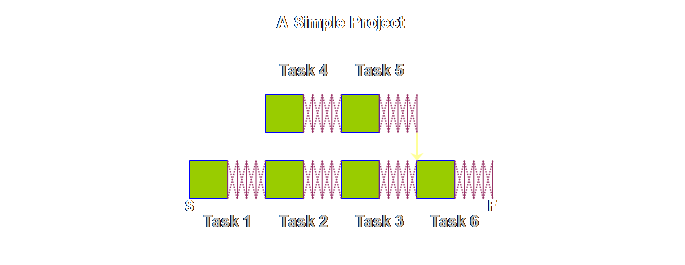

diagrams for the P&Q Question. If we were to draw

a very simple project, then apart from some different names, it would look

exactly the same, lets see.

The logic

diagram for production operations and project operations are exactly the

same, save for different labels. Let’s

put the two diagrams side-by-side.

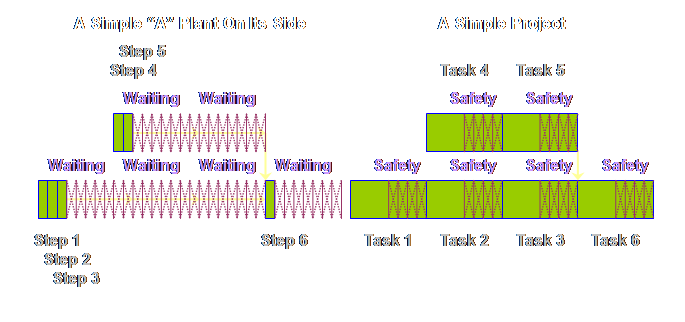

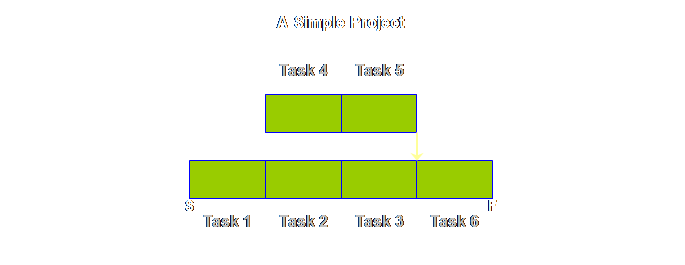

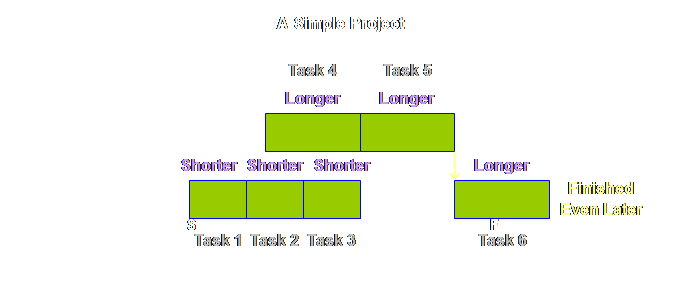

Let’s draw

each respective diagram so that the steps and tasks are somewhat proportional

to the time taken.

Let’s have a

look at this waiting in queues.

This raises a

question; there isn’t any waiting in projects – right? Well, not explicitly, and it isn’t called

waiting, it is called safety – “things” in production might wait but people

in projects don’t like to be seen waiting, so we have to call it safety. Let’s have a

look.

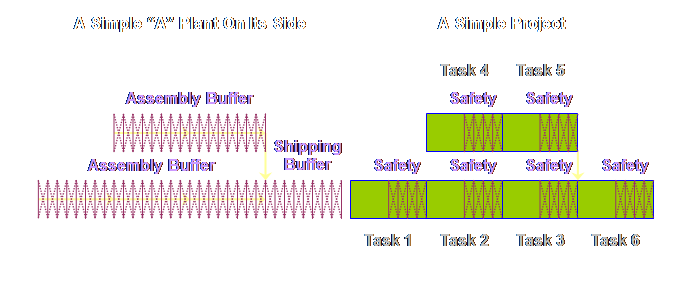

Having got

this far (even if you really don’t think that there is any safety in projects

what-so-ever), we can now show the apparent differences between buffering in

production operations in Theory of Constraints and buffering in project

operations in Theory of Constraints.

If buffering is an unfamiliar concept to you, then please wait a short

while. We need to bury the devil which

says that buffering in the two approaches is different. Once we have done that, then we can start

all over again with the vexed question of why we even have buffers in project

management. Let’s start

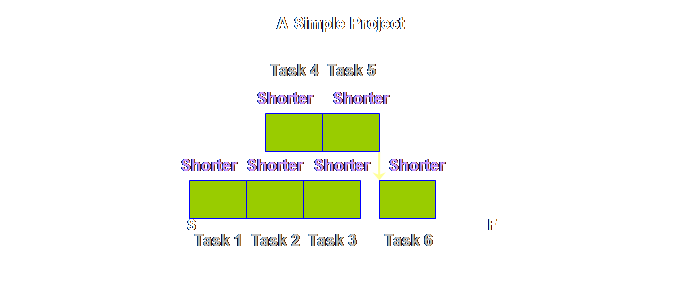

first with our “A” plant process. What

if we accept that we can move from an MRP schedule to a drum-buffer-rope

(DBR) sequence. In drum-buffer-rope

the only things scheduled are the start and the finish (and maybe the drum

but we will leave that out here). If

we accept that, then we can aggregate the touch time and we can aggregate the

waiting time. By aggregating the

waiting time we make the total waiting time available to the whole process. Let’s have a

look.

What happens next is that because the touch time in production

operations is so small (remember we have drawn it here 1 to 5 to 10 times too

large) it is ignored completely. This is what our process looks like as a consequence.

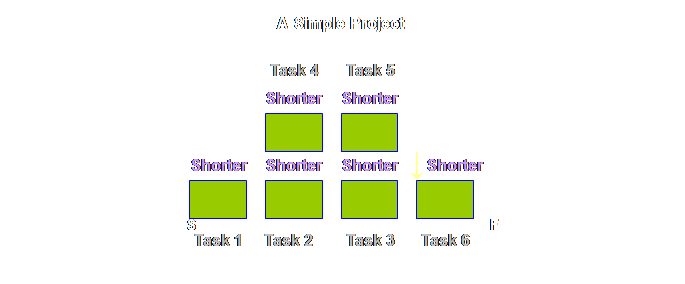

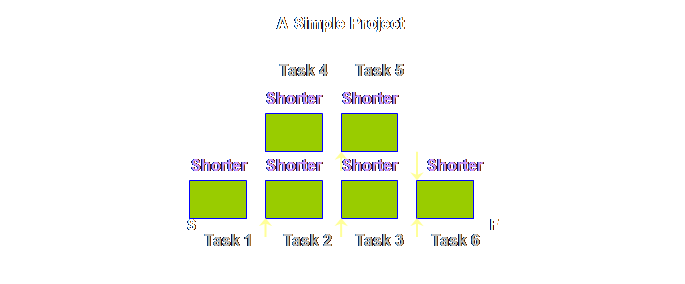

What then if

we accept that we can move from a Critical Path schedule to a Critical Chain

sequence. The only things scheduled

being the start and the finish. If we

accept that, then we can aggregate the touch time and we can aggregate the

safety time. By aggregating the safety

time we make the total safety time available to the whole process. Let’s have a

look.

Having made

these changes, do you see the apparent difference between the two sets of

buffers? To me, the buffers in

production operations appeared to occupy the whole of the process. In project operations the buffers don’t

occupy the whole of the project, instead they appear to be bunched-up towards

the end. However, the reality rather

than the appearance is more important.

The reality is that the buffers in both cases are treated in exactly

the same way, the only difference is that in one of the cases, production

operations, we can make a simplifying assumption and remove the touch time

from contention. That is all that we

have done that is different. The exact

mechanics in each case are a little different from this simple example. We have dealt with the production

operations case in detail in the production pages of this website, and we

will deal with the detail of project operations case over the remainder of

these project pages. Although the

detail may vary, the principle is the same (and in distribution and raw

material supply as well); we wish to identify and locate all the locally

distributed safety or waiting and aggregate it into one or several

strategically placed global buffers where the least total safety can be of the

greatest benefit to the system as a whole.

If we can remove safety that is embedded but wasted then we should be

able shorten the duration of the project without endangering the on-time

reliability of the completion date. In

fact, as we will see, we can substantially improve the reliability of the

completion date as a consequence. First,

however, let’s consider a few more aspects of touch time and variability in

production operations and projects. The touch time

in production operations is a very small part of the total time spent in the

process; most of the time is, in fact, spent waiting. In addition to the touch time being a small

part of the total, there is also little variability in its duration. This isn’t so much a case of the

repeatability of the tasks, but rather the mechanization of the tasks –

although, clearly, the more often a task is repeated the more likely we are

to want to mechanize it. And if we can

mechanize it, then automation is the next logical step after that. There are without doubt some manufacturing

tasks which have greater variability in their touch time than others; those

that use natural products and those that use manual labor are the two that

spring to mind. However, even in these

cases the variability is still not large. So where then

is the variability in production operations?

It is in the wait or queue time?

In fact, it is an assertion. I

can’t quantify the assertion because I have never seen a graph of variability

in wait time. There is genuine concern

about the amount of work-in-process and hence total wait time in a process,

but little interest in its variability between the same steps for the same

product. Its an invisible attribute. What then of

projects? Let’s start at the easy

place. Variability in wait time or

safety time is said to not exist, because safety time is said not to exist,

or at least insufficient safety time is said to exist because some tasks in

projects, and certainly almost all whole projects, tend to be late rather

than on-time or even early. In the

first instance then, it is better to view a project as a mirror image of a

production process. All the

variability in a project appears to be in the touch time of the task. Why should the

touch time of a task be variable? To

answer that we have to look at two things; § The nature of the task § The nature of the resources (= people) Let’s look at

the nature of the task first, and let’s just limit ourselves for the time

being to the realization that sometimes the subject matter of the task

unfolds swimmingly well, and equally, sometimes it does not. Thus there is some natural variability even

if a particular task is well known and well practiced. How about the

nature of the resources then? Just as

in production operations, people add variability to a task as well; people

unlike machines have good days and bad days (although I know a few machines

that seemed to be able to mimic this attribute well). If someone has not done a specific task

before, or the task is significantly different from prior experience, then we

ought to expect greater variability.

The task may take less time, it may take more. People with a large amount of prior

experience (both explicit and tacit knowledge) might turn out less variable

results than someone who is new. Let’s

summarize this. There

is variability around what is known Even if we

confine ourselves to what is known within the task of a project, then there

is variability. Because the touch time

is so large in proportion to the duration of the whole project, so too, is

the effect of any variability. In

production operations the task variability is small, the tasks are small, and

the shock absorbers for this, the in-queue waiting time, is huge. In project operations in contrast, the

tasks are large, the variability is therefore magnified, and the shock

absorbers are perceived to be small to non-existent. Let’s confine

ourselves for the moment to just this simple view of task variation. It is naive I know, but if we can understand

the effects in this simple case, then the more complicated issues caused by

uncertainty will fall out as a consequence.

We will address uncertainty, but not quite yet. Let’s have a look at the effect of

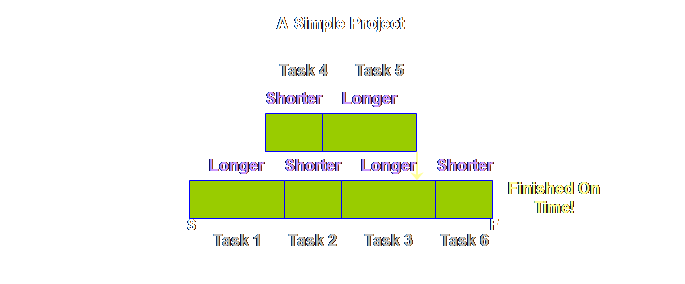

variability on dependent tasks in a simple project. Common sense

would seem to suggest to us that variability in project tasks ought not to be

such a bad thing. Surely over a number

of tasks the variability should average out?

Surely the larger the size of a project, and the number of individual

tasks, the more likely it is that the project will come in on time as the

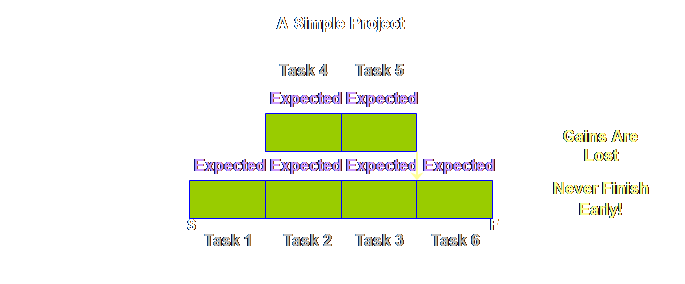

over-runs and under-runs average out? If this is our

plan,

Sad, is it

not? But it gets worse. Let’s see.

Multiple

dependency at convergences have quite an impact, but there are also other

dependencies wherever there is a “hand-off” between two adjacent tasks. We might not like to think of them in the

same terms as the convergence, but alas, the mechanics are exactly the

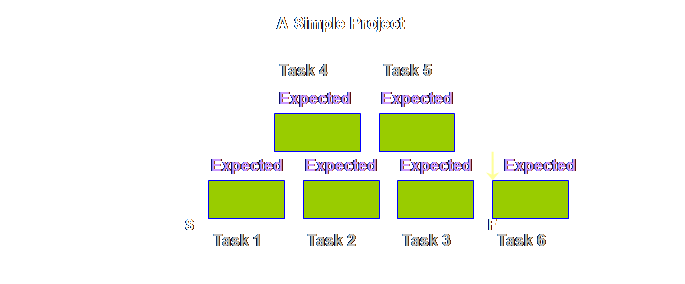

same. Let’s have a look. Let’s take an

extreme example where all of the tasks are completed in a shorter duration

than the estimate. The whole project

should finish early – right? If

everything went swimmingly well then this is what we should achieve.

The reasons

that we don’t get early starts to tasks and therefore early completions of

the whole project are manifold. Some

are mechanical, some are psychological (and real rather than imagined). Let’s have a look at the mechanical aspects

first.

If those are

the mechanical reasons (essentially people are busy), what are the psychological

reasons? The psychological reasons

belong more with the early finish of the preceding task rather than the early

start of the succeeding task. Ask

yourself; how often have you seen a task finish early? Probably not very often. Note, I didn’t say ask how often they do

finish early, I asked how often do you actually see it. You don’t see it because it is hidden. It is hidden for a number reasons. In reality we see the following.

Why would

people choose to slow down their task rather than to complete it early? One sound reason would be to protect the

very valuable safety time that has been so hard fought for and won on

previous occasions and which painful experience tell us that we need more

often than we don’t need. To lose that

safety now would put further tasks in future projects in jeopardy and that is

not something people wish to do at all. The

combination of successor task resources not being ready to start early when

there is an early finish, and predecessor task resources not being willing to

jeopardize future safety by finishing early ensures that gains in

individual tasks are lost and that whole projects never finish early. It sounds like a bold assertion, but I am

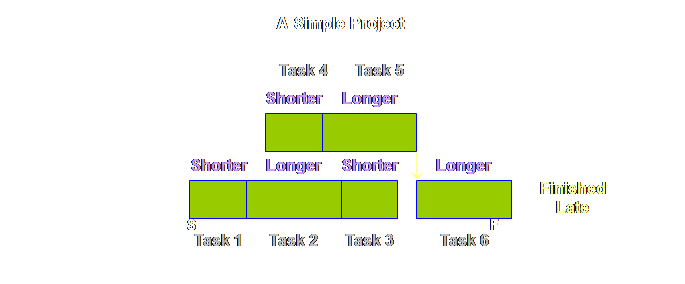

willing to entertain any evidence to the contrary. But this is

only half the story. We have only

looked at the extreme of tasks that are shorter than the expected duration

and thus have early finishes. What

about the other direction? What about

tasks that are longer than the expected duration or those that have late

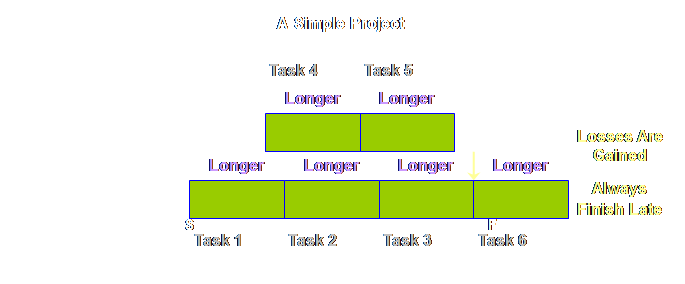

starts? Let’s see. It’s not nice. We start once

again with our simple project with our boringly uniform expected durations

and 6 simple tasks

How about less

legitimate reasons? Well, like the

early finish, we are unlikely to see such late starts recorded. Instead we are much more likely to see the

following.

Its a sobering

effect. We are just trying to do our

best, and yet it seems that at best our gains in individual tasks are lost

and whole projects will never finish early and at worst losses in

individual tasks are gained and whole projects will always finish late. Why do we put

up with this state of affairs? As we saw

earlier, shorter than estimated tasks can average out longer than estimated

tasks, and for that matter early finishes can average out late starts as

well. However, for a number of

mechanistic and psychological reasons this fails to happen. It fails to happen because safety is

embedded in each local task. If for

any reason we fail to utilize that safety it is lost to us for all time. If only the safety was available

in-totality somewhere to share out, rather than being embedded in each local

task, then surely we could resolve the mechanistic problems and maybe some of

the psychological ones too? The only

way to achieve this is to employ global buffering of the project. There is another reason why we must employ global buffering, an issue that so far we have

managed to avoid – uncertainty. So far we have

only looked at dependency in terms of how the completion of one task affects

the start of the next task. Successor

tasks are not only dependent upon the completion of the predecessor tasks,

they are also often contingent upon them.

That is, the nature of the successor task can not be fully determined

until the uncertainty is resolved by the predecessor task. This of course might only unveil further

uncertainty in the current task which is yet to be quantified. For example, a

project that includes foundation earthworks might encounter more difficult

ground or easier ground than prior testing had indicated. Outdoor projects are often contingent upon

the weather. This must be factored

in. Any form of overhaul and

maintenance project is contingent upon the condition of the equipment as

found after stripping the equipment down.

While our local garage may be able to say “it will depend upon what we

find,” project-sized operations must make a reasonable allowance for such

things ahead of the fact. Contingent

dependency and therefore uncertainty are common factors in projects. What happens

the first time a pharmaceutical company makes its first scaling-up experiments? A new recipe that works perfectly in lab

scale trials is moved for the first time to pre-production trials. Sure the rigs are the same as all the other

pre-production trials and yet there is novelty in the current mix. The chemistry, the quantities, the order of

mixing, the mixing itself, and the consequent “cooking” are all new. Will the yield and the quality be

sufficient? If not, what needs to be

changed, and if there is a change, how many more trials until we can bring

the project to market? Where there is

novelty, there is uncertainty. In

fact, where there are unknowns, there is uncertainty. There is one

more major source of uncertainty.

Let’s have a look. In a single

project environment resources may not be dedicated solely to the project

tasks. In many small businesses some

people assigned to project tasks may also be assigned to other non-project

tasks that must be fulfilled, such as day-to-day business or managerial functions. Such a case is very common in smaller

professional firms. In many firms,

both small and large, there may also be many concurrent fee-earning projects

each with its own needs and priorities.

Some people assigned to project tasks may be assigned to multiple

tasks in different projects (and some non-project ones as well). This would not be an issue if each task

could be carried out to completion before the next is started. Reality is that staff must chop and change

– multi-task – between different projects according to ever changing needs,

priorities, and mis-synchronization.

In fact, like fire-fighting in production operations, we often laud

such activity, even if it is to the detriment of the individuals concerned –

they get worn out – and the projects themselves – they are always longer and

later than we want. Uncertainty is

a dominant characteristic of project operations. If we found

that; There

is variability around what is known Then we must

conclude that; There

is uncertainty around what is unknown Unknowns and

the consequent uncertainty are a fact of life in project operations. How do we accommodate such

uncertainty? As it turns out, rather

well actually, lets see. Strange as it

may seem, it is very hard to find a novice production operation; even a new

firm on a “green fields” site that starts from scratch will endeavor to

employ people who have prior experience in the field, especially the detail

complexity of the specific endeavor.

Ditto, project operations. We

know uncertainty exists and we accommodate it by extending the duration of

the individual tasks. The more

uncertain we are, the more likely we are to seek longer task durations. The duration is weighed-up against prior

experience. Every task automatically

compensates or accommodates the uncertainty into the task estimate. The real issue, as with the case of simple

variation, is the existence of dependencies, and the local locking in of the

embedded safety. Greater uncertainty

simply compounds all the effects that we observed earlier due to dependency –

either mechanistic or psychological; any gains from individual tasks are lost

and projects simply don’t finish early.

Moreover, any losses in individual tasks are accumulated and projects

finish later and later. This need not

happen. There is more than adequate

safety allocated and embedded into each of the individual tasks. We started our

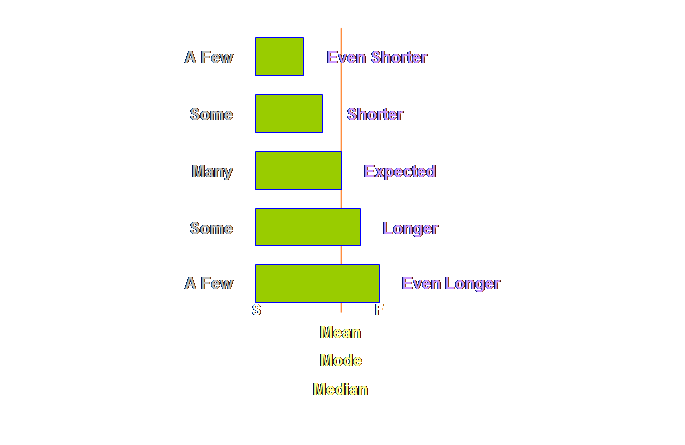

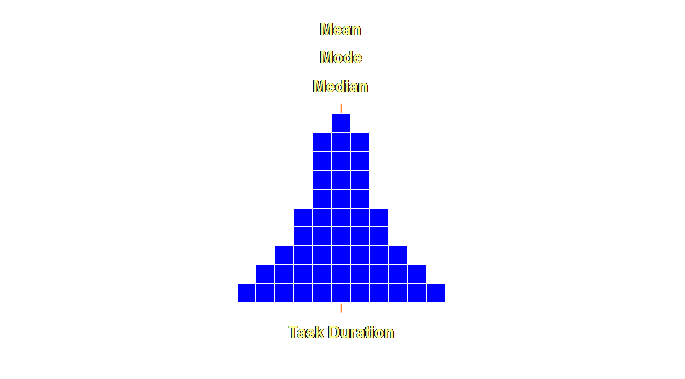

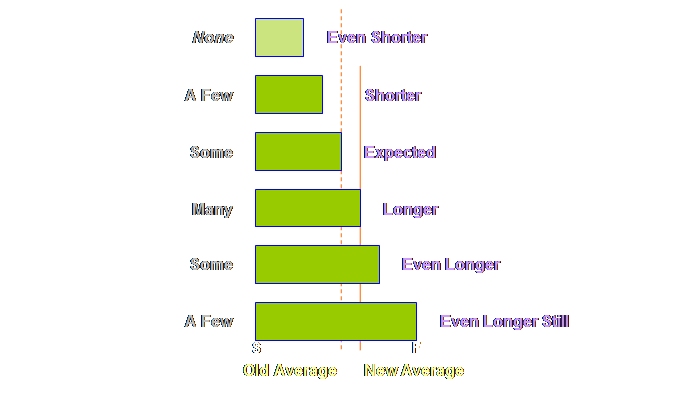

discussion on variability and dependent events with a simple project where

the under-runs and over-runs around an average task estimate cancelled one

another out and the overall effect was that the project finished on

time. This was based in part on the

notion that some sort of “normal” distribution is at work at the task

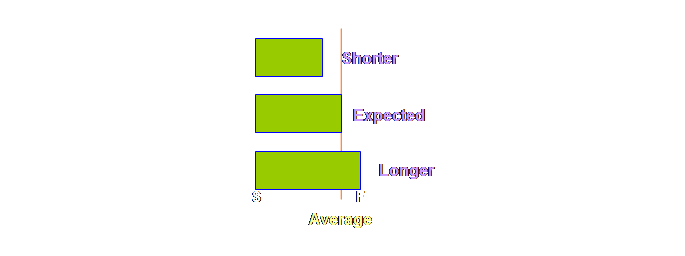

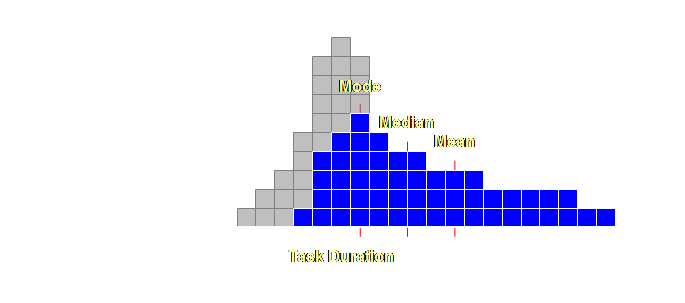

duration level. Let’s have a

look at this.

Let’s expand

this out a little more, a few more extreme values at either end and some

quantitative estimates as well.

Let’s have a

look at this.

Let’s add some

values to this distribution.

We embed the

necessary safety within each and every individual task duration

estimate. However, because this safety

is localized it is frequently wasted and our worst fears come true (again);

the overall project will not be completed on time. We view this as a vicious cycle of a

never-ending need for greater and greater safety estimates within the task

duration. If we could

make this localized safety accessible for any and all tasks within the

project by using buffers, then we would actually need less safety overall and

yet still finish on time. We need to

know how to access this safety, where to put it, and how much. These are essentially our task and buffer

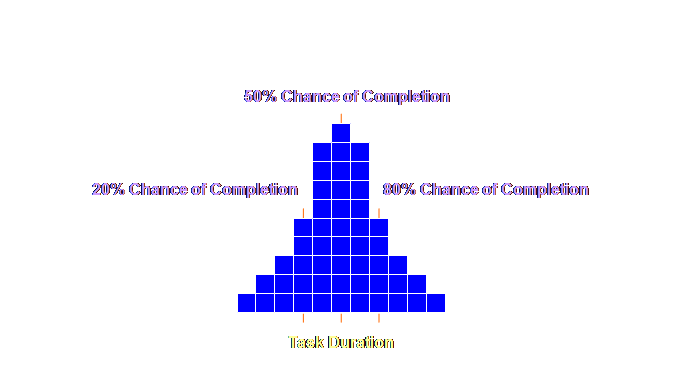

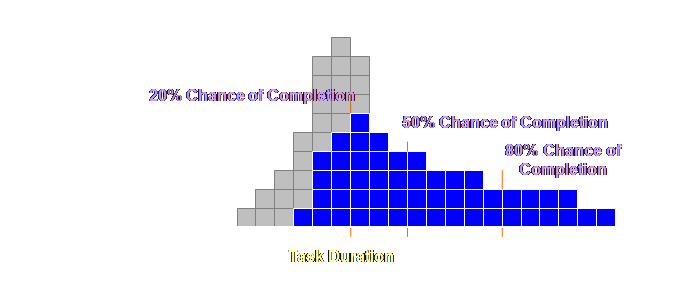

sizing rules. Let’s have a look. Buffer sizing

for projects, as for production operations, is based upon a rule of thumb, a

heuristic if that sounds better. It is

based upon a rule of thumb because this has been found to be thoroughly

effective over a very wide range of scope and scale of project management –

from the maintenance of jumbo sized commercial aircraft to the product

development of the tiny hard drives in our computers (5). Remember we are after effective and

implementable solutions; we don’t want ineffective nor un-implementable

solutions; the world is awash with those already. Let’s have a

look at the rule. We take our

initial project plan,

By halving the

task duration we bring it back to something around the 50% level. Then we will further protect this with

adequate buffers. This is ample

sufficiency as we will see. The

over-runs and under-runs around this estimate will average out due to the placement

of the buffers. Moreover, halving the

task duration has an important psychological effect that must not be

underestimated in its overall importance.

It stops the waste of unreported early finishes – because there is

precious little time to waste – and it stops the procrastination that causes

late starts – for the very same reason. Some

terminology. This shortened task time

has a number of names, it has been called the “trimmed task time” (4), “best

estimate” or “50% probable” (6). It is

also referred to as the “50% estimate,” the “focused task time,” and the

“reduced task time.” Take your pick. The reason

that there is more than ample sufficiency for individual tasks even at the

50% estimate is because we aggregate

the other half of the task, our safety, at the end of the tasks were it is

accessible to all of the preceding tasks. Let’s show

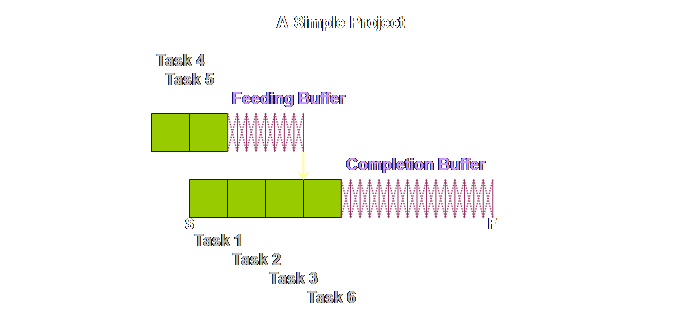

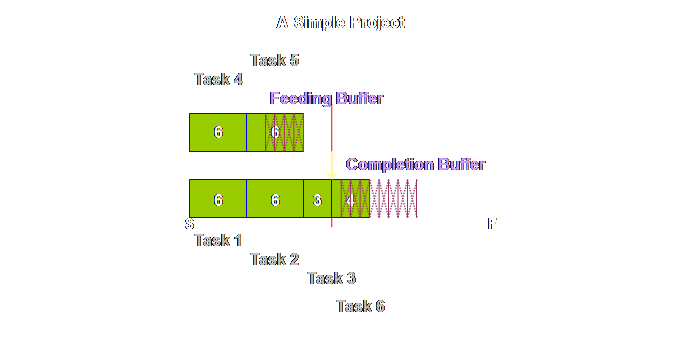

this.

Again, we have

some new terminology. The buffer on

the critical chain was initially called the “project buffer” (4) and this

terminology has continued to be used in a number of sources. However, a second term is also in use, that

of “completion buffer” (7). Once again

you can take your pick, however, here we will be using “completion buffers”

because that is what we are buffering and it is good to constantly remind

people on projects that the project will be completed within the completion

buffer – the term is self-reinforcing.

The feeding chains that arise parallel to the critical chain are

uniformly called “feeding buffers.” It is probably

better to keep the name “project buffer” as the name of the class, and

“completion buffer” and “feeding buffer” as members of the class, just as

buffers in production operations consist of drum buffers, assembly buffers,

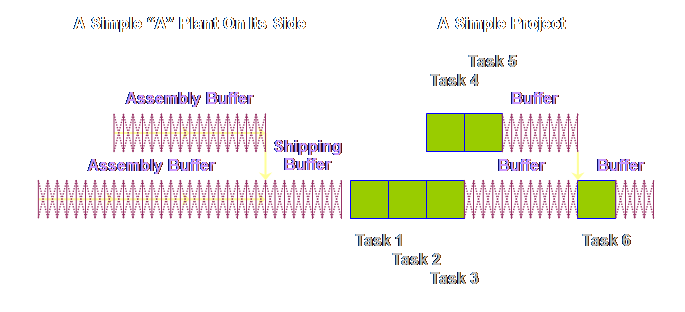

and shipping buffers. Returning to

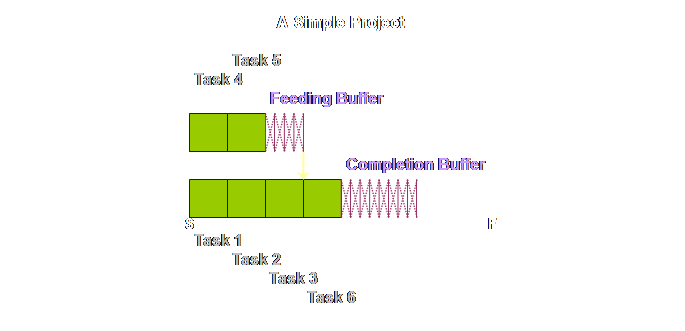

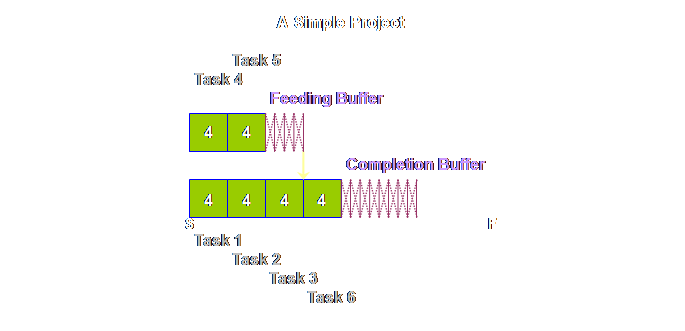

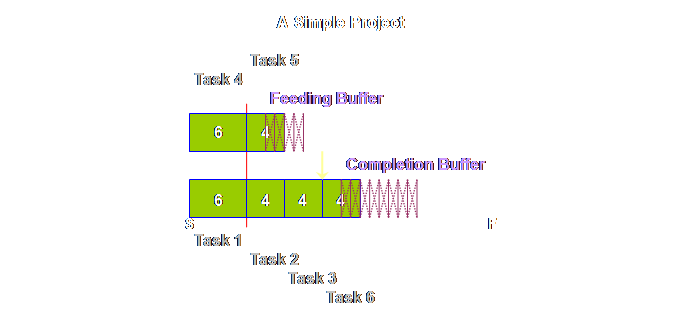

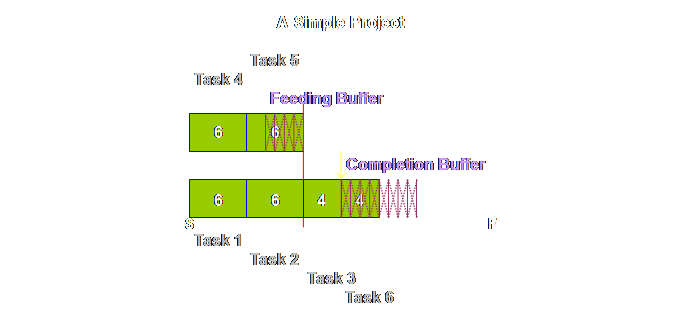

the detail of our simple project above, once again we find that tasks 4 &

5 are pushed back and that this has increased the total length of the

project. However, this is just an

intermediate step. Because the local

safety is now aggregated and located in just a few strategic places, it will

be better utilized, and we need less in total than we had before. The rule is

that we need only half as much aggregated buffer as we did as prior

non-aggregated safety. Therefore we

must halve the buffers (4). Let’s see what

this gives us.

Looking at it

another way, our new project duration is made up of 2/3rd’s task and 1/3rd

buffer. And this leads us to a more

generic buffer sizing rule. Regardless

of the task sizing rule that is used, the buffers

must be 50% of the task estimate.

The “completion buffer is 1/2 of the lead time of the (trimmed)

project” (7). Take care to

note; we now have a sequence, not a schedule.

Tasks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 are squashed up on the left; this doesn’t mean

each task is expected to be finished in the time allocated to each task, nor

that each will start immediately after the preceding one. Instead we still expect the normal range of

variation that we have experienced up until now, but that that variation will

be accommodated from the global buffers It’s taken us

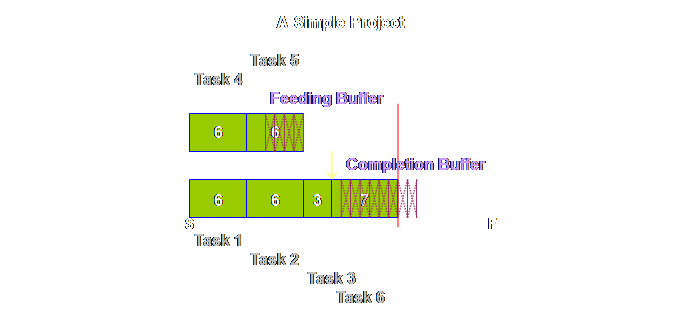

a long time to get here but I hope that it was worth it. Before we

finish however, let’s work through a project using our new found

knowledge. Here is the project plan or

sequence. We have added a some numbers

to make it a little more clear how the plan progresses.

Let’s step it

out another step.

Do you see

what we mean about a sequence. This is

not a schedule, we don’t know at this moment when task 6 for instance will

begin, nor for that matter when it will be completed. Let’s step it

out once again.

Let’s see what

happens at the end.

Hopefully this

simple sketch shows you the nature of the buffer; it is there to be consumed

in some rough proportion to the tasks at hand. Its location ensures that we can average

out the over-runs and the under-runs.

By aggregating the safety we can be equally effective with less, and

thus the whole project can be completed, not only on time, but also in less

time than we might otherwise manage.

We are also dealing with a sequence rather than a schedule; the start

and finish dates are fixed, but everything else is free to move as needed to

accommodate the variation and uncertainty in the project as it unfolds. Buffering of

the project plan is just one aspect of Critical Chain Project

Management. We’ve labored it here,

because there are so many subtleties that need to be explained. It should be pointed out that strictly

speaking we currently have a buffered Critical Path, and in the next section

we will show the difference that converts it into a Critical Chain. Also we have spent a lot of time on an

aspect of project management which is essentially project planning. The greatest gains from Critical Chain

Project Management don’t come from the planning but rather from the

execution. Having a buffered Critical

Chain plan, and knowing how to monitor the buffer against the plan gives

project managers a degree of control that is unimaginable with Critical Path

Method – as we shall see in the next page. Most of the

problems in project operations, like production operations, must be

psychological – our competitors don’t seem to have undue inability to produce

similar products/services and yet we all seem to have similar problems along

the way. Treating the problem as

psychological and “of us” rather than “of them” helps us to more readily

frame the solution. To put it more

bluntly, if nothing else works at least we should be open to changing our own

thinking. Recognizing the implicit embedded

safety in each individual task and moving it to a more compact and globally

accessible buffer is an important step along this path. A project is

an “A” plant tipped on its side. Both

project operation buffers and production operation buffers in Theory of

Constraints are exactly the same animal.

The differences come from the fact that we ignore touch time in

production applications and include it in project applications. Project

buffers allow us to aggregate system safety in a few critical places where it

is available to all preceding tasks and thus allows the effective averaging

out of tasks that take longer durations than expected with those that take

shorter durations than expected.

Aggregated safety as global project buffers is in fact more than

adequate compared to the case where safety is distributed locally and

embedded within each task. Therefore

projects can be completed on-time and within 75% of the previous estimates. However, there is more than just buffers to

Critical Chain Project Management, and we must now turn our attention to

these. (1) Karl Buckridge, personal communication 2008. (2) Goldratt, E. M., (1998) Project Management the

TOC Way. Avraham Y. Goldratt Institute

Limited, pg 40. (3) Newbold, R.

C., (1998) Project management in the fast lane: applying the Theory of

Constraints. St. Lucie Press, pp

25-27. (4) Goldratt,

E. M., (1997) Critical chain. North

River Press, 246 pp. (5) Kendall, G. I., (2005) Viable Vision:

transforming total sales into net profits.

J. Ross Publishing, pg 79. (6) Leach, L.P.,

(2000) Critical chain project management.

Artech House Inc., pg 110. (7) Goldratt, E. M., (2003-2006) TOC insights into

project management and engineering.

Goldratt’s Marketing Group (software-based tutorial). This Webpage Copyright © 2008 - 2009 by Dr K. J.

Youngman |