|

A Guide to Implementing the Theory of

Constraints (TOC) |

|||||

|

Draft

Copy This

page is “in draft” and on the internet so that I can more easily share it

with a limited number of particular people.

By all means feel free to read it, but be aware that I will continue

to work on it, off and on, until I am happy and this draft notice

disappears. Therefore at the moment

there may be loose ends and disjoints that still need to be addressed. Introduction You need to

develop the mura, muda, muri argument.

Define the terms as a list from Liker and Imai. Why do Westerns focus on muda, when mura is far more important. Could it

be our localized focus? Mura, or

unevenness feeds into and is the cause of the effects of muda

and muri.

Muda and mura, waste and strain are two

sides of the same coin. Reducing

unevenness is the way to address both of these issues. To focus only on waste reduction for

instance, reeks to much,

or is too often mis-construed to mean attending to symptomatic fixes rather

than addressing deeper systemic issues.

Moreover, the

things that I wanted to say seem to have already been said, and better said

by Jeffery Liker; Liker,

R., (2004) The Toyota Way, pg 10 I have

visited hundreds of organizations that claim to be advanced practitioners of

lean methods. They proudly show off

their pet lean project. And they have

done good work, no doubt. But having

studied Toyota for twenty years it is clear to me that in comparison they are

rank amateurs. It took Toyota decades

of creating a lean culture to get to where they are and they still believe

they are just learning to understand "the Toyota Way." What percentage of companies outside of

Toyota and their close knit group of suppliers get an A or even a B+ on lean? I cannot say precisely but it is far less

than 1%. What is the

reason for this? Liker,

R., (2004) The Toyota Way, pg 34 ... many books about lean manufacturing reinforce the

misunderstanding that TPS is a collection of tools that lead to more

efficient operations. The purpose of

these tools is lost and the centrality of people is missed. More over ... Liker, R., (2004) The Toyota Way, pg 7 The Toyota Production System is Toyota's unique approach

to manufacturing. It is the basis for much of the "lean production"

movement that has dominated manufacturing trends (along with Six Sigma) for

the last 10 years or so. Despite the

huge influence of the lean movement, I hope to show in this book that most

attempts to implement lean have been fairly superficial. The reason is that most companies have

focused too heavily on tools such as 5S and just-in-time, without

understanding lean as an entire system that must permeate an organization's

culture. In

most companies where lean is implemented, senior management is not involved

in day-to-day operations and continuous improvement that are part of lean.

Toyota's approach is very different. A

Personal Perspective OK fat

prospect is Ohno’s discussion of “misconceptions.” In fact probably the whole of Workplace

Management is grist for this page. But

misconceptions should be a central theme. The Toyoda’s

were systemisists, since at least (), how come then

that ... The roll of

Japan in the advancement of industrialization has intrigued me for a long

time. Of all the countries to

industrialize early on – The United States of America, Great Britain, France,

Germany, and Italy – Japan is the one that stands out above the rest. With the exception of the United States,

try and think of any enduring methodologies that have come from of these

other countries. And of all the

various methodologies emanating from Japan, the one that I want to really

address is the Toyota Production System.

The reason for this is that I believe that just as Deming and Taylor

were mis-understood and mis-interpreted, so too has Toyota. In fact it is curious that the previous two

examples of Deming and Taylor were correctly interpreted and understood in

Japan and incorporated into Toyota. It

becomes even more curious then that when Toyota methodologies were exported

once again to the West they are again mis-interpreted and

mis-understood. This ought to stand as

a warning that we in the West are missing the message whereas other peoples

are not. It seems that Western content

can move eastwards, the reductionist component of the context is often

stripped out, and the systemic component is implicitly absorbed. The Eastern content can move westwards, the

reductionist component is small and implicitly absorbed, the systemic

component is stripped out. There is a

continual filtering going on. If the West

rejects the essence of Deming and Taylor but the East doesn’t, and then the

West rejects the combination of Deming Taylor and Toyota then there must be a

powerful cultural message in this somewhere.

A message that could benefit those who want to listen. Indeed there

is a cultural message and I want to tease this out and show it to you. I believe that too many of us make general

assumptions about the industrial context in Japan and overlook crucial

specifics. Toyota becomes a case then,

the third case here, to illustrate the differences between the

systemic/global optimum approach and the reductionist/local optima

approach. This way I can avoid

addressing Nissan, Honda, Sony, Komatsu, Matsushita, NEC and a host of other

Japanese industrial companies that have also played a part in this story. Let’s work our

way through an explanation of the development of Toyota, and also something

of the development of Kaizen, they are part and parcel of one another. We will then use the “discovery” and

dissemination of Lean to show what is missed from the Toyota system in its

transition westwards, and what has been added. “The

year was 1950, and I was traveling aboard the old President Wilson en route from Hong Kong to San

Francisco. Our second port of call in

Japan was Yokohama, fire‑bombed like most Japanese cities, and a hodgepodge

of jerry‑built shacks and sheds. Some

sported brave facades like nothing so much as an American frontier town. To my amazement, I found, on a stroll

through a maze of postwar rubble, a gleaming, brand‑new Japanese style

teahouse, and invited myself in. The

proprietress, who seemed genuinely happy to find a foreigner at her doorstep

(she would be less happy today, I imagine), ushered me down a corridor to a

tatami room where she left me, and much bowing, to return in due course with

a cup of green tea and a plate of cakes.

This time she left for good, leaving me to drink my tea and enjoy the

room alone. Used

as I was to rooms filled with furniture, both in the West and in the decaying

splendor of the old mansions in Peking where I had lived for the past four

years, this room seemed everything they were not. I knew, of course, from photographs what a

Japanese room looked like. What I had

not detected in the photographs was the perfection of detail, the smoothness

of the woodwork, the luster of the lacquered tokonoma

step, or the subtle match of the grain of the wood in the slats of the

ceiling. It

was then that I looked at a corner next to the tokonoma, a place where the floor and two walls met. I had

been looking at corners all my life without paying them much attention, and

deservedly, since no corner I had ever seen prepared me for the shock the

perfection of this one produced. I got

up to look at it more closely, and stood gazing down in wonder. A simple joining of three planes at right

angles to one another, the corner was composed of a floor polished as clean

as a mirror, and two walls of smoothed clay tinted a greenish brown. (Years later I would discover that the

finest walls in Japan were make from mud found at the bottom of long‑used

rice paddies.) Perfectly made, the

corner was also perfectly clean. At

the point where these three planes touched, not a particle of anything, leave

alone dust, marked the knife‑edge precision of the joinery. This

simple corners, by the laws of nature neither larger nor smaller, nor

geometrically different in any way from any other corner in space and time,

had nevertheless shown me that there existed in Japan, despite war and

defeat, a living tradition of quality unequaled anywhere else in the world.” Why Japan? Why a page on Japan?

Why not Germany, or Italy or Great Britain. Each of these places were early to adopt

industrialization. As we have seen

Taylor and Taylorism was embraced in both German and Japan with

enthusiasm. So maybe we risk something

by discounting Germany and German cultural traditions. But we will return to these in the next

page on Organizations as Communities.

There are distinct and intriguing parallels. Why we must consider Japan is that as recently as

the mid-1980’s Japan was dismissed as a nation that” dumped” goods at “below

cost.” Of course the problem wasn’t

the Japanese, the problem was the North American map of reality that said

there is something valid called a “cost” – and we know how to calculate it. Which kind of reminds me of the medieval test for

witches by floating; it they floated they were a witch and if they drowned,

they weren’t. Now that “we” understand the error of “cost” we have

begrudgingly begun to accept that some aspects of Japanese industrialisation

are valid. But we have misunderstood,

or misinterpreted, the most important aspects. Have to discuss Schonberger first, then Lean second,

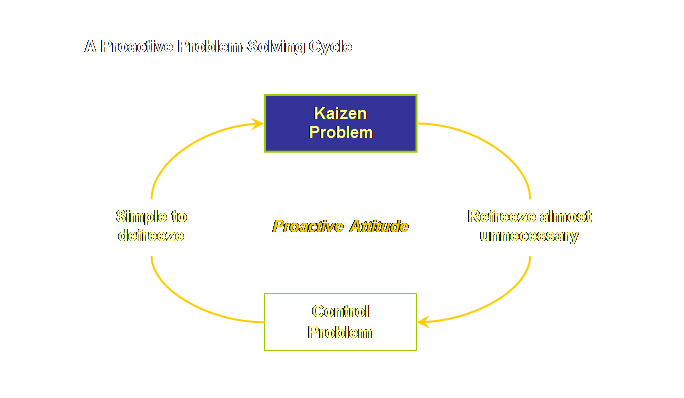

kaizen 3rd, and Toyota 4th. Diagram for incorporation into DBR and Distribution

on Buffer Management

Kaizen is (1) a state of mind, (2)

an set of approaches, (3) several groups of toolsets. Bugger me, Scientific Management had been translated

and published in Japan by 1913 (pg 491 of Kanigel – and up to 492. Examples of Western reductionism

transferred to Eastern systemism). Structure: is to ignore Lean I think, because it is

dealt in other places – this is the Kaizen page, the questions are raised

here and answered on Organizations as Communities. Kaizen = TQM + TPM + JIT. Need to address Tact time and include the

quote about work cadence from Kanigel (pg 545). Incorporate this back into Organization as

Communities later in favor of Road Runner. And it is bottom up. Maybe the classness of

Japanese society differs, one is a functional classism, the other, well I don’t know. Point out here that Ohno in Toyota (actually

probably Toyoda) made sure that job cards were developed and written by the

people using them. They were from a

more literal culture and time than Taylor’s.

Moreover they were operating serial mass production make-to-tolerance. Job cards assured the uniformity that was

essential if unrelated parts were later to fit together properly. If standardization was desirable in

Taylor’s time it was imperative by Ohno’s time. I used to cringe that some Japanese held Scientific

Management in high esteem. You have to

bring into this page Ohno’s comments about Taylor and (Ford) and also

Shingo. Why were the Japanese so

enamored with Taylor and Scientific Management? Answer, because they saw the larger

systemic context that eluded the social-Darwinists in the U.S. Begin here with what Kaizen is – a mindset. Where did we just see that – Taylorism? In fact we could mimic Taylor with a list

of what Kaizen is not. And then do that – from Imai Johnson, H.T., (1992) Relevance Regained, pg 45 By focusing people's minds on rates of output,

management accounting contributed greatly to the creation of waste in

American business after the 1950s. It

reinforced a general theme throughout American history ‑ the idea that

economic development entails expansion onto a frontier of virtually limitless

resources. Scale and speed, seen in

large‑scale capital investment justified by high volume output, was not just

an economic imperative. It was a

cultural norm. Servant leadership is very close to Bushido. Bushido is much closer to subordination of

the individual to to the state. Maybe we should conclude this section that

Bushido although not an explicit part of the modern state is an underlying or

underpinning ethic that has some relevance to the current leaders of the

country. Ditto at the end of Social Darwinism and

Taylor. Maybe individualism although

not an explicit part of the modern state is an underlying or underpinning

ethic that has some relevance to the current leaders of the country. Now you have your straw man, in place to

Organizations As Communities. You have

the argument ready to proceed with Johnson’s individual versus the

state. You repeat this is Paradox of

Systemism – as the ultimate local versus global conflict. Contrast here Eizo’s

comment about Kaizei and the previous about Social Darwinism. Then Imai in Gemba Kaizen chapter 11; argues that TQC/TQM

and TPM must be installed prior to JIT.

My experience in Japan at OSG was that companies with both good TQM

and TPM are plagued by MRP II-type scheduling systems. They have tremendous latent potential. For companies with this latent potential there are

three options; Find a more sophisticated MRP II or ERP system Proceed with JIT implementation Use a systemic logistical system – DRB or S-DBR or

Critical Chain I am sure many companies continue with the devil

that they know and employ more sophisticated MRP II or ERP systems. There are two good reasons for this; JIT systems best suite large-scale repetitive

manufacturers Knowledge of systemic logistical systems is very

poor Thus in many industries – batch producers of all

sorts – the latent potential of JIT can’t be tapped readily at all due to the

non-repetitive nature of the product.

Thus the kaizen implementation is somewhat like a 2-legged stool

instead of a 3-legged stool. Thus the

systemic approach of drum-buffer-rope allows this potential to be realized,

moreover it is totally compatible with the existing kaizen approach. Using the Imai/Toyota approach to classical kaizen,

then the stress has been on the quality end or quality, cost, and

delivery. Consider then that systemic

methodologies allow for an approach from the other end; the delivery end of

delivery, cost, and quality. Such an

approach still requires TQM and TPM to be successful, but now the logistical

system is driving the change rather than the quality system. The focusing system is different, the end

result, or the direction of the improvement is still the same. To a large extent it might not ever be possible to

test such a hypothesis because the quality movement has been so

pervasive. As we pointed out in

paradigms, it is much more likely that quality should be dealt with first,

because people will place that ahead of timeliness and not until quality is

satisfied does timeliness become a competitive advantage. Don’t forget to mention Imai’s Manageable Margin –

no this isn’t it, but somewhere he extends variation to the accounts as well. There is a strong cross-pollination of ideas between

kaizen and TPS – for instance see chapter six of Gemba Kaizen. What is the beef that Theory of Constraints has with

kaizen (TQM, TPM, and JIT)? There are

5 major ones; That throughput improvement isn’t immediate and significant That it is unfocused Problem identification is symptomatic rather than

systemic Treatment of safety in JIT Supplier dependency Let’s deal with these each in turn. The first reservation is that throughput increase

isn’t immediate and significant. Yet

Imai for instance suggests timeframes for benefits 4-5 years at the

most. Maybe this is not a problem but

rather the inability to stay the distance. The second reservation is that kaizen relative to

Theory of Constraints is unfocused.

And yet, SPC, TQM, Kaizen have a wonderful focusing mechanism known as

Pareto analysis. If there is a problem

then it seems to be a mis-application of the focusing mechanism rather than

the focusing mechanism itself. The third reservation is that, even if there is a focusing

system, then the elements of the focus are symptomatic rather than systemic,

and that there are insufficient mechanisms to burrow down deep to the

underlying root cause. In some cases

this reservation is valid. But there

is a “yes, but.” Yes, but, Eiji Toyoda said; and Taiichi Ohno

institutionalized the “5 whys.” Asking

“why” at least 5 times of the symptomatic problem in order to burrow down to

the root cause. And let’s be clear –

Ohno understood root causes to be policy as much as anything physical. This is well known within TPS/JIT practice

(reference Ohno, Liker) and Kaizen (reference Imai). Let’s be in no doubt either that it was root causes

that Toyoda and Ohno were after. In the fourth and final reservation, detractors

throw their hands up in the air and attack the buffering in TPS kanban; “if

there is a problem,” they say, thinking of the numerous stops in their own

process, “then the whole line will come to a stop.” Let’s deal with this one at two levels. At the first level; when something stops for long

enough the whole like stops. Not so,

for two reasons. First short sections

of line are decoupled (Liker) and this surely reflects occasional

interruptions. Secondly each section

has significant sprint capacity, that is 1:10 or

1:20 of staff who are unassigned. This

shouldn’t be confused with the Western concept of “floaters.” Of course it seems extravagant to have “redundant”

capacity but when you are so damn good – much, much better than your

competitors you can afford this. In

fact you can’t afford not to have it.

Without this staff capacity there would be no time for continual

improvement. Into this context we must now add the paradox that

causes most Western Lean proponents to mis-understand TPS/JIT. That is, in the West were line-stop

authority exists, it is generally believed that although the process can be

stopped at any moment it is not – and as a consequence it does in fact stop

more often. Failure to really attend

to problems as they arise causes the continuation of these and consequent

problems. In systems were the process can be stopped at any

moment and indeed is, then in actuality it stopped infrequently because each

problem is resolved and there are no further consequences. Line-stop authority offers nothing more than

an immediate feedback system and correction system. Companies ignore these at their peril. Maybe add the purist argument here about buffer

safety Fifth, and last in this list; what then of really,

really, big problems. These must cause

havoc with such close supplier relations?

However the evidence suggests that Japanese industry responds to these

crises with considerable agility.

Liker gives examples where a whole factory has been put out of

commission supplying a critical part ….. A more recent example is the destruction by fire of

…. Maybe we need to distinguish in TQM/JIT or Kaizen or

Lean between the Justification of context and the Justification of …. Japan had a lot of time and a systemic approach.

We see, in both Theory of Constraints and kaizen, a

maturation from production driven problems to system level problems. Hence the first 7 tools of kaizen were more

production oriented, whereas the new 7 tools are process or system oriented –

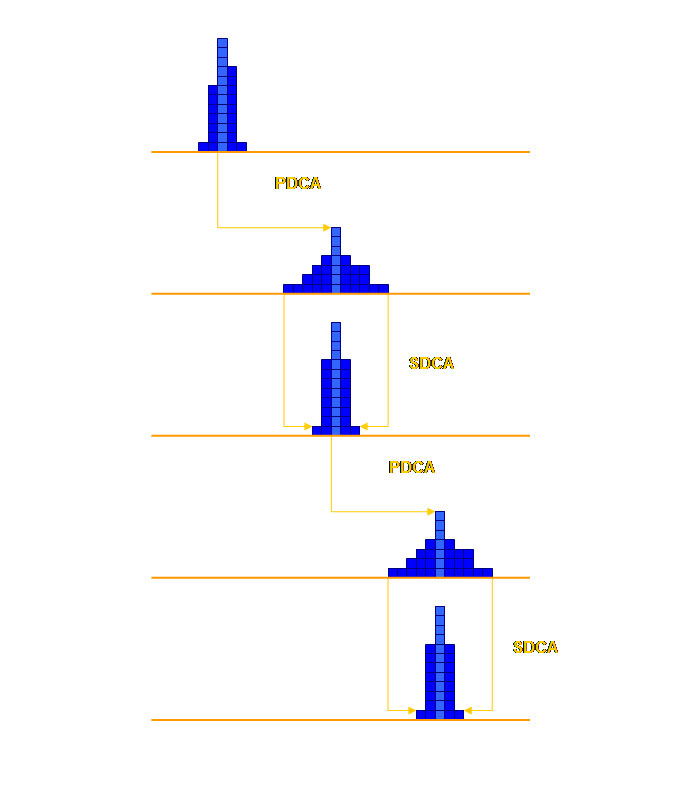

as the need grew or the approach matured (pg 94? of Imai). Link this back to the strategy introduction. Next line Improved Version

Graph of variation

Of course this is a very structured and

deterministic view of the process. We

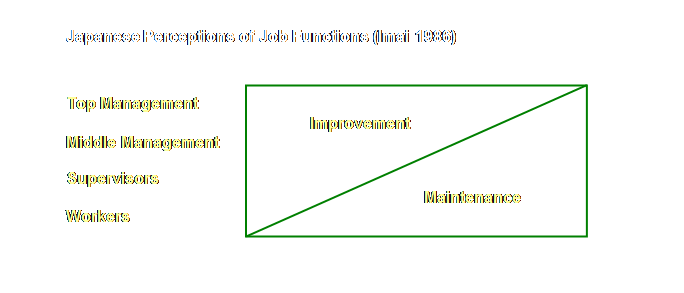

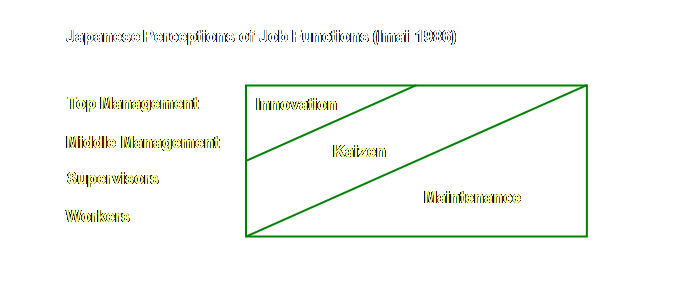

could summarize this as follows. Kawase’s 1st diagram here.

Also acknowledge the source of suggestions from

TWI. Contrast them later in

Organizations as communities US source different interpretation in Japan

different outcome. Imai, M., (1986) Kaizen: the key to Japan's

competitive success, pg 18 If we look at the manager's role, we find that the supportive

and stimulative role is directed at the improvement of processes, while the

controlling role is directed at the outcome or the result. The KAIZEN concept stresses management's

supportive and stimulating role for people's efforts to improve the process. On the one hand, management needs to

develop process‑oriented criteria. On

the other hand, the control‑type management looks only at the performance or

the result‑oriented criteria. For

abbreviation, we may call the process‑oriented criteria P criteria and the

result‑oriented criteria R criteria. P criteria call for a longer‑term outlook, since

they are directed at people's efforts and often requite behavioral

change. On the other hand, R criteria

are more direct and short term. There is a relevance to Theory of Constraints. Many batch-based serial processes appear to

be highly non-linear, in other words it is hard to predict from one day to

the next what will happen. Selecting a

constraint or a control point has the effect of fixing a non-linear system as

a linear system with one place and time known to all – the drum

schedule. The drum or constraint is

fixed and is protected by aggregation of time in front of the constraint. Once stabilization has occurred then it is possible

also to begin to exploit the constraint – that is improve it, and then to

incorporate these improvements into the normal scheme of things –

standardization. Defining the role of the constraints like this also

defines the roles of the non-constraints when they are incapable of supplying

the constraint in good time. Buffer

management also tells us where stabilization, improvement and standardization

is needed in the non-constraints. For

many of these activities the tools in utilized in Kaizen will be most

appropriate. Two graphs here

Theory of Constraints

Goldratt suggests that before the 5 step focusing

process there was no actual process for on-going improvement (Strategy

video). However this needs to be

qualified. I believe the qualification

is that; in the West, there was no explicit focusing process for on-going

improvement prior to the development of the 5 steps. Of course there is an exception to that in the West,

it is the Shewhart cycle (reference). In Japan Deming formalized PDCA within the context

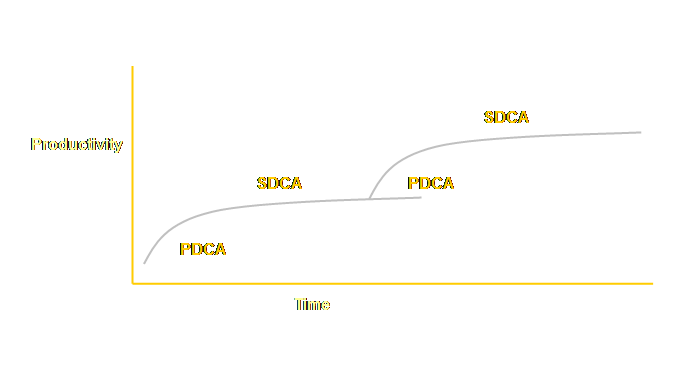

of Fig XX – design, production, sales, marketing, and customers. More broadly in kaizen this has become an

improvement & standardization framework – PDCA – SDCA. A process for continual improvement and

nothing less. PDCA – SDCA is, after

all, as much a conceptual framework as a sequence of actions. But these are explicit, what then of the implicit

processes. Well, kaizen is basically a

state of mind; a state of mind that some companies pursue as a process of

small and continual improvements. The

end result over time being substantial accumulated improvement. Yet, I suspect that if we were to ask these

companies where kaizen is so practiced what they actually do, they would be

at a loss to explain. Of course the

component parts of kaizen are explicitly documented, but the process overall

is implicit. The problem is when major component parts of kaizen

fabric are imported out of context; such as the Toyota production

system/just-in-time, or total quality management, re-amalgamated and given a

new name – Lean, for instance. Or

worse still, when just a selection from each major component – for instance

kanban without autonomation or without line stop authority. Then without the implicit guidance it will

be without focus. The reductionist methodologies taken out of the

systemic context of Japanese business (the better businesses that is) and

placed in a non-systemic environment fall on sterile ground.

It is the systemic environment that keeps these

reductionist methods outwardly focused on the goal of the whole system, in the

local environment they quickly become inward looking and self-perpetuating. Why then does Theory of Constraints appeal so

strongly? Because in companies that

have not yet invested the time and effort to develop kaizen, Theory of

Constraints applications “attack” the timeliness issue head-on (and quality

indirectly) with an effectiveness that is, I will argue, still unknown within

kaizen. Kaizen development times (quote Imai). Moreover, the timeliness aspects of just-in-time are

still largely constrained to large-scale repetitive manufacturing. Within a kaizen framework of; List it here The logistical solutions of Theory of Constraints

(drum-buffer-rope, critical chain, replenishment and distribution) work like

a hand in a glove. Operability Let’s use the term “operability” to cover both

timeliness and quality. This way we

can better understand the differences between the Theory of Constraints and

TQM/JIT. In Theory of Constraints its great strength is

towards timeliness. However it is not

possible to address timeliness on its own without some consequent improvement

in quality. We discussed this passive

aspect of quality improvement much earlier in the section on Quality/TQM

II. In TQM the great strength is

improved product quality in the process.

However it is not possible to address quality on it owns without some

consequent improvement in timeliness. The Toyota Production System may be viewed as rather

special for attacking both ends of the spectrum simultaneously through single

minute exchange of dies and statistical process control, both complementing

and reinforcing each other. And of course that is essentially what Ford had

achieved preciously in his early automated plants. So we are left with this curious dichotomy of both

timeliness and quality in our search for better operability. Proponents of the Theory of Constraints

have often disparaged other quality based initiatives, and in turn proponents

of the various quality approaches have often failed to consider using Theory

of Constraints. In part, and I stress

“in part,” this is because each approach does indeed deliver some of the

results sought by the other end-point approach. This leads each approach to be somewhat

dismissive of the other’s end-point view – even though neither approach by

itself is capable of achieving the best possible operability at the time in

question. So what then are the other parts that cause this

dichotomy? Well there are two major

points; TQM (and statistical process control and six sigma)

and JIT-type activities when translated to LEAN initiatives are often

unfocussed even though these approaches originally advocated using the Pareto

Principle as a focusing mechanism.

This destabilizes the results and is viewed by Theory of Constraint

proponents as a reason not to fully pursue LEAN initiatives. In Theory of Constraints applications the failure to

remove old measures and consequent behaviors destabilizes the results too and

is viewed by LEAN proponents as a reason not to fully pursue Theory of

Constraint initiatives. In both cases, the cause of the problem is the

failure to develop a systemic approach and instead allow a reductionist

approach to prevail instead. For too long Theory of Constraint proponents have

claimed some sort of moral high-ground by proclaiming that TQM initiatives

are unfocused. This is not the case;

it is the mis-application of the implementation that causes the lack of

focus. TQM has a focusing mechanism,

the Pareto Principle, it should be used. Equally LEAN proponents claim Theory of Constraints

to fail when they have failed to support the implementation in a consistent

manner with its principles. Whenever we decrease variability in either

timeliness or quality we increase operability – we improve operability. How can we visualize this? We have a continuum that is also

transforming into opposites. Timelines

at one end and quality at the other.

Well, it really quite simple.

Let’s use our hands. Hold your right hand out in front of you, fingers

outstretched, and the palm facing you.

The plane of your hand defines the axis for quality. Maximal quality (and minimal product

variation) at the base of the hand decreasing towards the fingertips. Now hold your left hand out in front of

you, fingers outstretched, and the palm facing downwards; middle fingers

touching. The plane of this hand

defines the axis for timeliness.

Maximal timeliness (and minimal process variation) at the base of the

hand decreasing towards the fingertips. To use the analogy further. Get a colleague to make a tight fitting

paper strip around one thumb and palm.

This is the probability space for maximal timeliness and minimal

quality or maximal quality and minimal timeliness – depending upon which hand

you choose first. The shape is an

elongated oval. Now have someone move

that sleeve to the middle where your middle fingers touch. The sleeve will

become circular and your colleague will have to support it so that it is

equidistant from your fingers at all points.

This is the probability space for maximal timeliness and maximal

quality. At his point we have minimal

variation and maximal operability.

This is where we should all be aiming. Do you see the trouble now? If we pursue any one approach then after we

reach the mid-point we will begin to degrade the opposing factor. Well maybe that is too hypothetical, but I think

that it serves as a useful analogy to help understand the strong dichotomy

that seems to exist between the proponents of the different methods. In actuality we are all aiming for the same

mid-point – minimum variation and maximal operability – but from different

sides of the continuum and from opposite perspectives; and yet, to do so

successfully we must employ more and more of the opposing perspective if we

are to achieve our goal. There is a modifier.

Much earlier on we did mention that it was much more likely that this

process was sequential rather than contemporaneous. That is, the move from cottage to mass

production and made-to-fit to made-to-spec probably stressed the need for

product quality rather than process timeliness. Thereafter process timeliness became more

important. There are of course two

cases were both appear to have been arrived at simultaneously; Fords Rouge

River Plant, and Toyota’s just-in-time.

In both cases these systems have moved towards the mid-point in our

analogy from the reductionist end. Maybe I need to add a note from Johnson (and

probably Kaplan and Cooper) about costing setups using ABC to show increased

costs over shorter batches – as an example of treating each entity as uniform

(search “Cooper” in Johnson to find the right reference). Even though they apply perfect logic, it is

the logic of the wrong paradigm (and in fairness Johnson would agree to an

extent pg 150 first example). Pow! We see

the same generic problem in business schools as we see in publicly traded

companies. The choke point or

bottleneck between the explicit and external and the implicit and the

internal. Same structure different

problems, same result. Draw it so that you can transfer it from one to the

other. The failure of those living in an explicit

transactional world to truly understand those working in a tacit process

world. Kaizen Imai considers kaizen to be a mixture of about 16

different approaches, but especially Ishikawa’s TQC and Ohno’s

just-in-time. But maybe this misses

the point, the cultural context in which all of these localized improvement

processes operate. To say that kaizen does not have a focus is

incorrect. It’s

focusing method is the Pareto Method, as coined by Juran. The problem begins when it is applied more

broadly and in a less disciplined fashion. TOC primarily improves both timeliness and quality

by removing waste (as does kaizen) but provides no

mechanism other than smaller batch sizes and the philosophical and practical

distinction between process and transfer batch sizes. In this respect it is almost passive in its

approach. Kaizen in comparison begins to offer active and

pre-determined solutions that can follow-on from where TOC begins. Of course the power of the more focused

approach of TOC means the kaizen improvements are even more effective,

however, often the passive improvements are so great that kaizen directed

improvements aren’t required (yet).

A good place as any for this; Shingo, S., (1990) Modern approaches to

manufacturing improvement, Robinson, A., editor, pg 22 European and American managers are busy studying and

experimenting with kanban, Just‑in‑Time (JIT), and other features of the

Toyota production system. Without an

understanding of the system's basic concepts and implications, however, truly

effective innovation in production management will not be achieved. Maybe a good place also to put the following; it is ironical that waste elimination is given such

prominence in the academic texts that describe Japanese manufacturing

techniques when it was the Gilbreth’s in America at the turn end of the

1800’s who had perfected waste elimination as an improvement methodology and

codified and championed its application Toyota Original JIT concept

Because the reduction in work-in-process is

generally localized, then improvements in product quality and process

timeliness are also localized. Thus

global increases in timeliness especially, need significant local increases

in timeliness everywhere – but that too is what Toyota have handsomely

achieved over many years of on-going improvement Later concept after TQM was formally adopted (in

1980)

Page 91 of Imai, remember that Total Quality

Management didn’t start at Toyota until around 1980, and Kanban around 1962. So it is not until the early 1980’s that

the synergy occurs (not correct because I understand from Walton that Toyota

won the Deming Prize in 1965-66 after Nissan won it in 1960) We can see the interaction here between process

timeliness and product quality; product quality and process timeliness. If he works for you, you work for him. Japanese proverb Similar to the concept of reciprocity – Senge pg ##

- no can’t find a reference to it anywhere; Liker, Nonaka, Kaisha. Be careful here.

Eli Goldratt in SLP 1 and Stein in his TQM II make the distinction

that it is not just the identification and exploitation of a constraint that

becomes a focusing mechanism for stand alone Total

Quality Management or Lean initiatives, but moreover it is the buffer and

buffer management that is the main driver for application of these

techniques. I goes without saying, so I will say it, that when

Theory of Constraints rather than Total Quality Management or Lean is the

underlying management philosophy, the Total Quality Management and Lean

toolsets are the ones that are used to address the problems identified by the

buffer management regime. Contrast Kaizen’s localized view of the next process

is the customer with the more systemic view of needing to understand my

customer’s customer’s customer. Car Park Probably for Leadership D

examine new-found techniques (do change) Or D

examine new-found techniques (change the business) There is a personal cloud hiding behind this common

system cloud; D

examine new-found techniques A better verbalization D

do change and take risk Car Park We

have been here before. In at least 3

different place and times, we have come so close to the necessary

understanding, and then, in the West at least, we have allowed our underlying

personal experience override what is necessary. Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints is just

the fourth attempt at this problem in the last 3 or so generations since the

onset of mass industrialization.

Hopefully, each time we take a step closer to understanding what

really must be done. Let’s

take a step backwards for a second and summarize a few things. As far as Theory of Constraints is

concerned, it is the new kid on the block, its only 25-30 years old,

depending on where you want to draw the line.

And it started out as the deterministic scheduling of manufacturing

operations. Deterministic scheduling

in a different sense to that used in other approaches in that it considered

that there was finite capacity.

Eventually this was refined to finite capacity at just one place – the

constraint. Since then it has embraced

supply chain and projects, both different aspects of the same thing. It also comes with its own approach to

management accounting that allows rational decisions to be reached. These aspects and more are addressed in earlier

pages of this website. Go have a look,

go follow the reference trail for greater information. What

then were the precursors? Strangely,

the first systemic approach was that of Frederick Taylor and Scientific

Management. Although Taylor is largely

vilified, he is also hugely mis-understood.

Standing at the start of mass industrialization he understood the

importance of a systemic approach long before anyone else. That we continue to selectively mine his

work to substantiate our own mis-understandings only fuels our own continued

ignorance. We are doubly bound and we

don’t even know it. We are trapped

within a paradigm and we can’t see it. Taylor

died in 1915 – of pneumonia just to press the point about how little removed

we are from such tragedy – his colleagues continued on with various “flavors”

of his approach. The removal of wasted

motion strictly belonged to his contemporaries and sometime collaborators;

the Gilbreths. During the period that

the work of the Gilbreths flourished, Walter Shewhart developed a statistical

approach (1924) that was to become the cornerstone of W. Edwards Deming’s

quality movement. At

about this point the 2 threads of Taylor and Deming start to interweave via

the Japanese. A company called Toyoda

Spinning and Weaving – which was famous enough in its own right that pre-war

school children were taught of their exploits in class – started to build

motorcars. The values of the Toyoda

family, and the skills of Taiichi Ohno and Shigeo Shingo produced what is now

know as the Toyota Production System. It has strong antecedents in

Taylorism. It, like Taylorism, is also

strongly systemic. This is a value

that comes from Japanese culture. The

work of Taylor was strongly absorbed between the First and Second World Wars

in the United Kingdom, Japan, Russia, and Germany. I suspect it is very hard for us today to

recognize just how immense this change in thinking was at the time. Deming

and Shewhart’s statistical process control was well known to some Japanese

industry prior to World War II via the U.S. electronics industry – glass

valve manufacture to be exact.

Post-war, Deming did continue to teach this in Japan (after 1950) but

his primary effort was to inculcate that only a system-wide or systemic

approach, driven by leadership at the top would succeed. Deming had seen statistical process control

bloom in war-pressed industry in the United States, only to virtually

disappear once the hostilities ended.

He recognized that only through leadership from the top was he going

to be able to show just how significant a change his understanding could

bring about. Now

here comes the sad part. All of this

is known. We also know that in 1911

Taylor was lamenting that people were mistaking the mechanism of his

methodology for the essence. So too

with Deming’s work and the work of Toyota.

People like to pick out the bits of the content (the easy bits mind

you) without picking up on the context.

We go for the detail and leave the dynamics behind. I’m

no apologist so here comes more bad news.

Six sigma is of the fashion in healthcare at the moment (the managerial

part that is, the medical part has always used statistics), unfortunately,

this is just the detail taken from Shewhart and Deming, repackaged yet again,

and on-sold. It is to my mind a local

optimization approach. You can test this assertion, just tell me how many

more patients any single health system has been able to treat as a

consequence. Sure there will be some

isolated successes, but nothing overall.

And its not because

the system is too complicated, its because the

approach knows nothing of the leverage points within the system. So too with benchmarking; straight out of

the 1920’s and still no improvement, no improvement because it is

reductionist, isolated and fails to undress the underlying principles of why

some places might be better than others.

It sets to mimic rather than understand. Finally

the Toyota Production System has come of age in healthcare. Of course first it had to be rediscovered

and re-branded as Lean manufacturing.

Only recently do we see due acknowledgement of its original source. Now

it might just appear that I have succeeded in running down 3 cornerstones to

modern industry, this is not the case, I have profound respect for each of

these approaches; Taylor, Deming, and Toyota.

But I have nothing but contempt for their partial derivatives, the

“lite” implementations of six sigma, lean, and the various crossovers. Here

is a challenge; someone find for me just one health system that uses the

Toyota logistical system known as kanban – anywhere within its process. There are definitely places where it is

applicable, it would be interesting to know anyone who has ever made this

commitment. I am told by

manufacturing colleagues that if you want to check up on “A3 report” on the

internet you will be swamped with healthcare examples. This is interesting. It has come from lean. But let’s add some notes of caution

here. Lean is a “Western”

interpretation of Toyota in particular and Japanese Kaizen in general. It is not the first interpretation, it is

merely the latest when the contrast between eastern and western manufacture

could no longer be explained away.

Richard Schonberger had drawn Western attention to Japanese

manufacturing techniques in 1982 () and went on to re-label this as “World

Class Manufacturing ().” Several years

earlier Norman Bodek had started Productivity Press which brought to the

West, English translations of Japanese books by Shingo, Ohno, and a host of

others equally important (). If that

weren’t enough Imai had published directly into English his books on Kaizen

starting in 1986. Many people picked

up on these methodologies. Why we had

to wait until 1990 for Womack, Jones, and Roos and their lean description ()

is beyond me (well its not, as we will see in

moment). Lean is still a Western

interpretation. Liker estimates that

only around 2% of so-called Lean implementations are true Toyota

implementations (). Why is this? In short –

culture. Some colleagues now want to

“computerize” A3 reports – so that they are available to everyone. This speaks volumes about the gulf that

exists between East and West. In Japan

an A3 report is a visual and tactile and immediate representation of the

problem, the proposed solution and the progress to date, in the vernacular it

is a “living document” and it is usually found at the foreman’s desk. Anyone can find it there and managers go

there to check it. Perish the thought

that managers should show an interest in the floor here. So we sanitize and computerize our A3s and

we don’t even know how much harm we have done to the process. A3 reports are a means not and end. Consider

“value stream mapping.” Can anyone

find in any of Ohno’s work the term or even the similarity for “value stream

mapping?” Value stream mapping

“appears” on the scene in Womack and Jones’ 1996 book (), it is not a

Japanese approach. It is based upon

the premise (truism) that “activities that can’t be measured can’t be

properly managed.” Unfortunately it

overlooks the work of Deming (and wasn’t he the guy who was in Japan in the 1950’s onwards) who was adamant that “It

is wrong to suppose that if you can't measure it, you can't manage it ‑

costly myth ().” It’s almost too much

to expect anyone to pay attention to the man who so much helped to improve

Japanese systemic understanding that we invent new explicit approaches to

replace former tacit methods. Do you know

how Ohno used to do this? Take a piece

of chalk, draw a circle on the floor and get subordinates to stand in it

until the flow became clear to them. I

know of no better approach. If we were

to go to the actual place, see the actual problem and talk to the actual

people we would probably have to take some responsibility. It is far safer to draw an explicit flow

diagram and not take any responsibility.

This is the real value of value stream mapping – the avoidance of

responsibility. Let’s just

take one more example. This time from

Lean healthcare ala the National Health System (NHS) of Great Britain. In particular a new apparatus known as the Glenday Sieve. A

little bit of poking around will reveal that this is nothing more than the

power rule observation attributed to the 1800’s Italian economist, Vilvrado Perato. That it is being used to “volume”

measurements in healthcare is hardly unique, that it as to be called a new

name though is. Perato analysis

forms the backbone of kaizen analysis of independent events, why, why, why,

go and rename it? Is there a need to

make healthcare different from all other human endeavor? If so, maybe this is why it has taken so

long for “modern” management methods to permeate into this industry. (1) Johnson (1992) Relevance Regained pg x. David Kidd, director emeritus of the Oomoto School of Traditional Japanese Arts, in Japanese

Style: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc./Publishers, pg xi (19) Schonberger, R. J., (1982) Japanese

manufacturing techniques: nine hidden lessons in simplicity. The Free Press, 260 pp. (20) Schonberger, R. J., (1986) World class

manufacturing: the lessons of simplicity applied. The Free Press, 253 pp. (21) Schonberger, R. J., (1996) World class

manufacturing: the next decade: building power, strength, and value. The Free Press, 275 pp. () Bodek, N., (2004) Kaikaku: the power and magic of

lean, a study in knowledge transfer.

PCS Press, 392 pp. () Imai, M.,

(1986) Kaizen: the key to Japan’s competitive success. McGraw-Hill, 259 pp. () Imai, M.,

(1997) Gemba kaizen: a commonsense, low cost approach to management. McGraw-Hill, 354 pp. (24) Womack, J. P., Jones, D. T., and Roos, D.,

(1990) The machine that changed the world.

Simon & Schuster Inc., 323 pp. (25) Womack, J. P., and Jones, D. T., (1996) Lean

thinking: banish waste and create wealth in your corporation. Simon &

Schuster, pg 258. () Liker, J.

K., (2004) The Toyota Way: 14 management principles from the world’s greatest

manufacturer. McGraw-Hill, 330 pp. () Deming, W.

E., (1994) The new economics: for industry, government, education. Second edition, MIT Press, pg 35. This Webpage Copyright © 2008 by Dr K. J. Youngman |