|

A Guide to Implementing the Theory of

Constraints (TOC) |

|||||

|

Draft

Copy This

page is “in draft” and on the internet so that I can more easily share it

with a limited number of particular people.

By all means feel free to read it, but be aware that I will continue

to work on it, off and on, until I am happy and this draft notice

disappears. Therefore at the moment

there may be loose ends and disjoints that still need to be addressed. Taylor

was a systemist.

Probably since ( ), how come then that ... I have

an admission to make – Adam Smith Pin

specialization and factory However

specialization isn’t something new Tryol

Alps Story Some

suggest that the factory is the starting point. Certainly

it marks another important change the movement from cottage (and therefore

family) to factory and the wider community and all the management issues that

brings about. Issues that probably

didn’t really come to the fore until piece work disappeared. If you

have trouble today, think back to Deming’s time when Hawthorne had 10,000 etc So

maybe it is the factory that is most important. Taylor

was on the cusp of a wave of factory and industrialization. Introduction Taylor

wrote; “In the past man has been first; in the future the system must be

first.” (pg iv 2nd

paragraph) He wrote this in the introduction to his 1911 treatise “The

Principles of Scientific Management.”

It was incredibly prescient, but it must have been incredibly

difficult for most people to relate to at that point in time. Today it sounds almost Owellian,

but that reflects more than anything our own failure to learn anything in the

almost 100 years that have elapsed since. Scientific

Management, or Taylorism, or time and motion studies, are common enough terms

that most people in business will have bumped into at one time or

another. The term Scientific Management,

however, wasn’t coined until 1910, some 30 years after Taylor began his quest

into industrial engineering. The term

came to embrace not only the time-based work of Taylor and his immediate

associates; Henry Gantt, Carl Bath, and Horace Hathaway, but also the

motion-based work, or rather avoidance of wasted-motion-based work, of Frank

and Lillian Gilbreth. Taylor

was far ahead of his time and consistently misinterpreted by most of his

contemporaries. This misinterpretation

has important parallels with Deming 60-70 years later. Moreover, the misinterpretation carries

through to today, where our additional misunderstanding of the cultural

context of a century ago makes the confusion even greater. In prior pages I have treated Taylor and

Scientific Management as the

arch-reductionist, for that is how his principles have been almost

exclusively interpreted. I don’t

intend any time soon to change those pages to reflect my change of

opinion. But changed my opinion I

certainly have. In

1997 Robert Kanigel published a monumental biography on Taylor, The One Best

Way; Frederick Winslow Taylor and the enigma of efficiency. I read this in 1999, and I have to say I

read it as reinforcing my existing bias that Taylor was a reductionist. It wasn’t until 6 years later that I read

Taylor’s 1911 treatise; The Principles of Scientific Management, and

substantially changed my opinion. This

current page is based almost wholly on these two sources. There are (at least) two other sources that

I would like to include, but haven’t as yet.

They are Frank Copley’s 1923 biography; because it is close to the

date of interest and sympathetic to the cause, and Daniel Nelson’s 1992 work

on Scientific Management after Taylor.

Taylor died aged 59 just 5 years after the publication of

Principles. It is important to

distinguish what Taylor said, and what others said who came after him. I

am fascinated that contemporary authors continue to perpetuate the straw-man

that is depicted as Taylor, it is almost as if by constructing this straw-man

we absolve ourselves of responsibility for investigating the true cause of

our current dissatisfaction. And I am

fascinated that out of all the work that Taylor and his colleagues did, some

of which fundamentally changed our industrial world, it is the short pig-iron

carrying experiments that receive so much attention, and so much

opprobrium. While working on this page

my respect for Robert Kanigel has increased.

While, often, where opinion is allowed, he falls into expressing the

reductionist interpretation, but equally when reporting fact he is aware of

the dichotomizing power of Taylor’s approach. “Even today, for every critic who views him as devil, another sees him

as saint. And the split doesn’t hew to

easy left-right lines. Only the

slightest shift in perspective, it turns out, changes Taylor’s hat from black

to white (Kanigel pg 17).” Kanigel

is indeed correct to use the word “enigma,” but it is not efficiency that is

enigmatic, it is us, ourselves, and our response to the modern industrial

environment that we have created that is enigmatic. And the clue to solving this enigma comes

from Louis Brandeis, a contemporary of Taylor’s and the one responsible for

coining the term “scientific management.”

If we can understand Taylor’s contemporaries, then we can understand

where we fail in our current interpretation of this man and his intent. Well,

firstly let me express another bias. I

spent a substantially period of time working within a number of factories

which produce rotary cutting tools. In

fact the largest factories of their type in the world. One of these made high speed steel endmills

and drills. High speed steel as we

will see was invented by Taylor and Maunsel White at Bethlehem Steel. And although manufacturing is in many

people’s minds no longer sexy, something called “IT”. or

knowledge economy apparently is, this simple invention, high speed steel, is

used in more basic industry than most people would care to imagine. To me this alone would warrant Taylor a

substantial place in history. I think

also that it provides a context that too many people chose to ignore, and yet

once presented informs most of his other work. So

what I propose to do is present a “potted” biography of Taylor’s industrial

background, within which we can see the rationale for Taylor’s approach to

Scientific Management. If we do this

within the social context of the day then we can understand how his

contemporaries interpreted his work and why, and equally how they

misinterpreted his work and why. The material, unless otherwise stated, is from Kanigel (1997). Let’s

go.

Taylor

began an apprenticeship at Ferrell & Jones, known as Enterprise Hydraulic

Works, a pump manufacturer, in 1874.

His family had the means and he had the ability to pursue higher

education at a time when few others could, but chose the more usual option of

an apprenticeship. He set out as an

apprentice patternmaker but sometime during this began a second

apprenticeship as a machinist. In

1878 he moved to Midvale Steel, first as a laborer and then as an ordinary

machinist. He became a gang boss in

1879 at the age of 23, and rose to foreman by late 1880. Once he became gang boss he came up against

soldiering and tried to overcome over the next two years. “Taylor still wasn’t getting what he deemed a full day’s work out of

the men; but he was getting twice as much as before (Kanigel pg 170).” His

men, although employees, worked on piece rate, the prevalent scheme at the

time. Rises in productivity were

usually met with a reduction in piece rate and as a consequence productivity

remained static. Skilled machinists –

craftsman – could argue against any increase in work rate on the basis of

rule-of-thumb about depth of cut and speed of the machine. Their world was one of tacit knowing and

Taylor having received that training had, in my opinion, the insight to

realize that explicit knowledge of what could and couldn’t be done was lacking. Without explicit knowledge it is the gut

feel of management that more work can be done versus the gut feel of the

machinists that more work can’t be done – piece rate complications excepted. In

1880, Taylor sought and gained permission to carry out metal cutting

experiments. He did this on an

overhauled machine, cutting tools were made from one batch of tool steel, Results were

recorded in code so that unconscious bias was not introduced. “The first object was to resolve once and for all that much disputed

issue of every machine shop, the precise profile to which the tool’s cutting

edge should be ground (Kanigel pg 176).” After

6 months he found that within a large range the profile didn’t matter. With this “non-result” Taylor was allowed

to continue with further tests for the next 2 years, tests that truly

required the commitment of the ownership as the steam engine running the

whole works had to be slowed down in order to allow the finer graduations in

cutting speed. Nevertheless this work

did yield tables of best feed and speed for certain conditions and allowed a

30% increase in output of the work’s 6 tire boring machines. Moreover, the machines could now be run by

laborers or machinists helpers rather than first-class machinists. Between

1880 and 1890 Taylor rose from foreman to master mechanic to chief draftsman,

and then to chief engineer. During

this period Midvale Steel expanded and prospered, a new machine shop

quadruple in size was built.

Importantly it had integral cutting tool cooling by water, a discovery

that allowed cutting speeds to be raised by a third. During this period Taylor also made his

first tentative steps to relate physical exertion – manpower – to the work

done. With no consistent results he

gave up. It

was also during this period that Taylor began to time individual operations

and to write job-cards for individual operations. The value of this was that he could

assemble different operations into a whole job and know with some certainty

how long an old job should take or how long a totally new job might

take. The job-cards also reduced the

cost of jobs by ensuring that they were done in a correct fashion. Associated with job-cards he also introduced

differential piece rates. If a certain

rate was exceeded then the whole day’s work, not just the additional work,

was rewarded at the new and higher rate. Taylor

using his knowledge of metal cutting was sure that the rough turning of axles

could be increased from 3-5 per day to 10.

He used his differential piece rate to try and bring this about. On the 3rd trial he was successful. By 1887; “men previously earning $1.50 a day turning

axles earned double that and produced two to three times as much work

(Kanigel pg 212). In

1887 Henry Gantt arrived at Midvale as Taylor’s assistant. By substituting logarithmic graph paper for

linear graph paper he helped to bring a whole range of metal cutting

solutions (correct feed and speed) before them. During this time Taylor also designed and

oversaw the building of a 75 ton steam hammer which he designed to flex with

the blows and for 12 years pounded away at 3 times the speed of other hammers

with less upkeep and repair. Pulp

Mills – 1890 - 1893 In

October 1890 Taylor left Midvale, lured to Madison by William Whitney and the

offer of general management over the construction and operation of two pulp

and paper mills using the new Mitscherlich

process. The mills were successful in

producing good grade pulp, but there were problems; competitors found was

around the patent protection, the energy consumption was vastly greater than

the owners were lead to believe, many aspects appear to have been

under-designed prior to Taylor’s arrival. Taylor

introduced differential piece rates in the two mills; He never wholly succeeded at Madison but largely did at Appleton. Within a year and a half, virtually every

operation there – ‘from the time our materials arrive in the yard,’ wrote

Taylor, ‘until they are shipped in the [railroad] cars’ – was on piecework,

mostly applied to work gangs rather than individuals (Kanigel pg 254)”. This

is important in so much as it refutes a more recent and maybe common

view. Liker (2004 pg 197) argued that

Taylor “strictly” focused on individual incentives for productivity, whereas

Toyota distributes work to, and measures the performance of, teams. We can see that in the beginnings of this system

that such “strictness” did not apply.

Indeed there seemed be a healthy dose of pragmatism in Taylor’s

approach in that there was very little or no time measurement used to

establish the differential rates. This

pragmatism is an approach that would be revisited in future applications too. The

pulp company, however, was caught up in an economic slow-down and the mills

were shut. Taylor satisfied that the

mills were working well had already left. Itinerant

– 1893 - 1898 During

the next 5 years Taylor essentially became a consulting engineer/management

consultant. This included developing a

management accounting system that allocated overhead not just to wages but

also to machines on the basis of the time used, as companies sought to

determine the performance of differing products. He wrote a paper on the economics of power

belts, still the main form of power transmission at the time. He started a series of metal cutting

experiments on two brands of

self-hardening steel (tungsten hardened steel) using an electric powered

lathe, however, the heating was done by eye, different temperatures yielding

different colors, and the results were inconclusive. More importantly, however, he determined

that these more expensive tool steels should not be reserved for special jobs

such as hard forgings, but should be in general use. In

1895 he presented to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers a paper on

his differential piece rate system as an answer to labor unrest. Unlike the two prevalent systems of the

day, Taylor did not take historical output as his base but rather sought to

establish a new measure of what constituted a fair day’s work. This work was reprinted in several

engineering publications and also in the United Kingdom. In

1996 Taylor engaged Sanford Thompson to extend Taylor’ ideas about time study

in machining to various manual trades such as building and plastering, with

the intent of publishing books on each trade.

Taylor himself, began working, or rather consulting to a streetcar

works in Johnstown, Pennsylvania.

Amongst his repertoire of improvement methods he once again deployed his

differential piece rate system.

Importantly, as in the pulp mills and contrary to his paper on piece

rates, the rates were not based upon stop-watch studies. “As at Midvale, piece rates at Johnson were broken down by operation

but were apparently not based on stopwatch studies (Kanigel pg 299).” On

returning to Simonds Rolling Machine Company, a maker of ball bearings,

Taylor installed a differential piece rate system – again without time-based

study. In the case of ball bearing

inspection, this, and other refinements, lead to; ... thirty-five women were doing the work

that a hundred and twenty had done before, making sometimes double their

previous wages (Kanigel pg 304). It

also seems to be the first instance of substantial labor reduction rather

than absorbing improved productivity and output into an expanding

market. Although Taylor reckoned that

output per worker was now more than double at every stage this was

insufficient to avoid the board voting to shut down the works in 1898. Taylor had previously been approached to work at

Bethlehem Steel and in 1898 the offer was extended once again and

accepted. He began to work at Machine

Shop No. 2 – a quarter of a mile long – and Bethlehem Steel’s worst bottleneck. He set about his standard approach;

requests for water-cooled cutting tools, new belting standards, pre-grinding

tools and so forth. He also urged the

use of self-hardening tool steel for all roughing cuts. Taylor sought to

demonstrate the benefits of Midvale self-hardening steel at Bethlehem. He had a large electric lathe built with a

40 horse power motor which could accommodate a 4 foot diameter cylinder of

steel. Unfortunately, Midvale

self-hardening steel turned out to be the worst of 5 tool steels in the

trial. Taylor prevailed upon the management to allow new

tests that would allow him to run Midvale steel through a series of

systematic heat-treat temperatures.

Taylor and Maunsel White, Bethlehem Steel’s metallurgist, took the

original self-hardening steel and put it through a series of controlled heat

tempering experiments. They took it

way past the color which was known to ruin tool steel and yet found it to cut

at a speed of 25 feet per minute. They

continued to heat samples further until they obtained a cutting speed of more

than 50 feet a minute. “This in a shop where, on average, day after day, work was cut at nine

feet per minute. A tool made from

ordinary Midvale self-hardening steel – heat-treated at a temperature every

machinist and blacksmith in the place knew with certainty would reduce it to

rubble at the first swipe against the work – was cutting four or five times

that fast (Kanigel pg 314).” The experiments continued for the next 9

months. Before they were through

Taylor reckoned a dozen men had performed 16,000 individual experiments and

reduced 200 tons of steel to chips.

With the use of a platinum-rhodium wire pyrometer, developed by Le Chatelier in France, Taylor and White were able to

determine that chromium-tungsten tool steel when heated beyond 1550 °F

became ruined – this is what had caused the initial failure. However, when heated beyond 1725 °F hardness returned and continued

to increase until around 2200 °F, close to the material’s melting point. The new heat-treat allowed cuts to be 40% deeper and

feed rates to be doubled. The combined

effect was that the work rate was triple the old rates (327). Moreover, Taylor engaged Carl Barth to

reduce the data into a workable slide rule.

Gantt had managed to create a crude one, Barth one that allowed all

the parameters of machine cutting to be feed in and the one or few solutions

to be calculated – within 20 or 30 seconds.

Not only had Taylor managed to substantially increase the speed of

machining, he had also managed to remove rule-of-thumb and replace it with

explicit calculations. During the steel cutting experiments Taylor embarked

on a set of experiments related to pig iron handling. Bethlehem had accumulated 80,000 tons of

pig iron while prices were low, and as the price began to pick up again the

pig iron was sold and then shipped by rail.

Although these experiments took only 2 months and resulted in reducing

the number of yard laborers from 600 to 140 over the next two years, in my

opinion they seem to account for more critical comment on Taylor, Taylorism,

and Scientific Management than all of his other work combined – as though

this epitomized Taylorism and everything else did not. This maybe is an unintended consequence of

pig iron handling being one of two stories that Taylor used to impress his

ideas on the public. The only way to move pig iron in 1899 was by manual

labor. Taylor wanted to introduce

differential piece rates to the process.

He established that a 16.5 ton load could loaded onto a car in 14

minutes. He extrapolated this to

arrive at 75 tons per man per day on a continuous basis, and then took 40% of

this to set a standard of 45 tons per man per day allowing for breaks and

delays. “This was at least double – and probably closer to triple – what

laborers had been able to manage throughout history” (Kanigel pg 320). It is telling that of 40 men especially selected to

do this work, only 3 were able to load enough to earn substantially

more. It may be that Taylor simply

overestimated the nature of such continuous heavy laboring. Nevertheless, a reduction from 600 to 140

men suggests that substantial improvement in productivity was still

achieved. Part of this appears to be

due also to his shoveling experiments.

Taylor determined that 21 pounds was the optimal load for a shovel and

had different shovels made for different densities of materials shoveled. This became the other story most often told

to the public. “In the end, through time study, piece rates, and other measures, the

cost for each ton of material handled in the Bethlehem yards was halved, and

the place was being run as no such place ever had before” (Kanigel pg 334). Taylor

also extended functional foremanship to Machine Shop No 2.,

however even with all of the advances monthly output hardly exceeded the

monthly output for the 5 preceding years.

The problem seemed to lie in too much idle time – the machines did cut

faster but were idle more often as well.

Henry Gantt suggested a task-plus-bonus scheme to get the shop moving;

that is people were paid a bonus if all of their work for the day was

completed as compared with Taylor’s more complex differential piece

rate. As at $$$$ and at $$$$$

scientific time-based study gave way to pragmatism. Production jumped from 624,000 pounds of

rough-machined work to 1,6000,000 pounds in 3

months. However, it was too late for

the $1,100,000 spent and two years of effort made and his services were

terminated. The

(Character) Assassination Of Frederick Winslow Taylor This is from Robert

Simons 1995 Harvard Business School Press book “Levers of Control (1). “Frederick

Taylor's work Principles of Scientific

Management, published in 1911, likened individual workers to

machines that could be fine‑tuned in pursuit of efficiency. Using time-and-motion studies, Taylor

raised the acts of shoveling and handling pig‑iron to a science. Managers were enjoined to study repetitive

tasks carefully or hire experts to do so, to experiment to improve prescribed

procedures continually, and to ensure that workers complied with these

practices by offering piece rate incentives.

In Taylor's view, workers would only respond to financial

incentives based on defined performance standards.” This

is from Richard Liker’s 2004 book “The Toyota Way” pp 143‑144 (2) “Under Taylor's (1947) scientific

management, workers were viewed as machines who needed to be made as

efficient as possible through the manipulations of industrial

engineers and autocratic managers.

The process consisted of the following: § Scientifically

determining the one best way of doing the job. § Scientifically

developing the one best way to train someone to do the job. § Scientifically

selecting people who were most capable of doing the job in that way § Training

foreman to teach their "subordinates" and monitor then so they

followed the one best way. § Creating

financial incentives for workers to follow the one best way

and exceed the performance standard scientifically set by the industrial

engineer. Taylor did achieve tremendous

productivity gains by applying scientific management principles. But he also created very rigid

bureaucracies in which managers were supposed to do the thinking and workers

were to blindly execute the standardized procedures. The results were predictable: § Red

tape § Tall,

hierarchical organizational structures § Top‑down

control § Books

and books of written rules and procedures § Slow

and cumbersome implementation and application § Poor

communication § Resistance

to change § Static

and inefficient rules and procedures.” Also

pg 197 (3) “Taylorism is the ultimate in external motivation. People come to work to make money ‑

end of story. You motivate workers by

giving them clear standards, teaching them the most efficient way to reach

the standard, and then giving them bonuses when they exceed the

standard. The standards are for

quantity, not quality.” This is from Margaret Wheatley in her 1999 book “Leadership and the new science (4)”, pg 159 “The work of

Frederick Taylor, Frank Gilbreth, and hosts of followers initiated the era of

“scientific management.” This was the

start of a continuing quest to treat work and workers as an engineering

problem. Enormous focus went into

creating time‑motion studies and breaking work into discrete tasks that could

be done by the most untrained of workers.

I still find this early literature frightening to read. Designers were so focused on engineering

efficient solutions that they completely discounted the human beings

who were doing the work. They didn’t

just ignore them, as has been done more recently with contemporary

reengineering efforts. They disdained

them – their task was to design work that would not be disrupted by the expected

stupidity of workers.” These

are fairly stereotypical comments about Taylor and Scientific

Management. They, and my reading of

Robert Kanigel’s monumental biography “The One Best Way; Frederick Winslow

Taylor and the Enigma of Efficiency,” tell a common interpretation. Common, but I believe fundamentally

incorrect. There certainly is an

enigma in efficiency, but it has to do with us and our interpretation of

efficiency, not with efficiency per se. This

enigma is clouded further by the distance of time and culture. Taylor worked and wrote at a time of

transition from craftsmanship to mass production, at a time of transition

from manpower to mechanical power, and in a vastly different social context

which I believe is glossed over in more recent interpretations. Let’s

contrast these extracts with some lengthy ones from Taylor Starting

Near The End – 1911 Taylor died aged 59 in 1915, in 1911 he published a

treatise called “The Principles of Scientific Management.” The term Scientific Management had only

been coined in 1910 by the lawyer Brandeis to encompass the many and varied

aspects that Taylor and his associates had investigated in the previous %%

years. “The principal object of management should be to secure the maximum

prosperity for the employer, coupled with the maximum prosperity for each

employé. The words “maximum prosperity” are used in their broad sense, to mean

not only large dividends for the company or owner but development of every

brand of the business to its highest state of excellence, so that the

prosperity may be permanent. In the same way maximum prosperity for each employé means not only higher

wages than are usually received by men of his class, but, of more importance

still, it also means the development of each man to his state of maximum

efficiency, so that his natural abilities fit him, and it further means

giving him, when possible, this class of work to do. It would seem

to be so self-evident that maximum prosperity for the employer, coupled with

maximum prosperity for the employé, ought to be the two leading objects of management, that even to

state this fact should be unnecessary. And yet there is no question that,

throughout the industrial world, a large part of the organization of

employers, as well as employés, is for war rather than peace, and that

perhaps the majority on either side do not believe that it is possible so to

arrange their mutual relations that their interests become identical.”

The majority of these men believe that the fundamental interests of

employés and employers are necessarily antagonistic. Scientific management, on the contrary, has

for its very foundation the firm conviction that the true interests of the

two are one and the same; that the prosperity for the employer cannot exist

through a long term of years unless it is accompanied by prosperity of the

employé, and visa versa; and that it is possible to give the workman what he

most wants – high wages – and the employer wants – a low labor cost – for his

manufacturers.” The

first 5 paragraphs from Taylor’s 1911 work “The Principles of Scientific

Management” tell us so much about the intent of this man. Develop

each of the points in there, labor them – then move to page 2 “No one can be found who will deny that in the case of any single

individual the greatest prosperity can exist only when that individual is

turning out his largest daily output. The truth of this fact is also perfectly clear in the case of two men

working together. To illustrate: if

you and your workman have become so skilful that you and he together are

making two pairs of shoes in a day while your competitor and his workman are

making only one pair, it is clear that after selling your two pairs of shoes

you can pay your workman much higher wages than your competitor who produces

only one pair of shoes is able to pay his man, and that there will still be

enough money left over for you to have a larger profit than your competitor. In the case of a more complicated manufacturing establishment, it

should also be perfectly clear that there greatest permanent prosperity for

the workman, coupled with the greatest prosperity for the employer, can be

brought about only when the work of the establishment is done with the

smallest combined expenditure of human effort, plus nature's resources, plus

the cost for the use of capital in the shape of machines, buildings, etc. Or, to state the same thing in a different

way: that the greatest prosperity can exist only as the result of the

greatest productivity of the men and machines of the establishment ‑ that is,

when each man and each machine are turning out the largest possible output;

because unless your men are daily turning out more work than others around

you, it is clear that competition will prevent your paying higher wages to

your workman than are paid to those of your competitor. And what is true as to the possibility of

paying high wages in the case of two companies competing close beside one

another is also true as to whole districts of the country and even as to

nations which are in competition. In a

word, that maximum prosperity can only exist as a result of maximum

productivity.” Then

add here maybe that this sounds like Deming – only 84 years too early. Taylor

was concerned about soldiering. Taylor, F. W., (1911) The Principles of Scientific Management, pg 3 “The English and American peoples are the greatest sportsmen in the

world. Whenever an American workman

plays baseball, or an English workman plays cricket, it is safe to say that

he strains every nerve to secure victory for his side. He does his very best to make the largest

possible number of runs. The Universal

sentiment is so strong that any man who fails to give out all there is in him

in sports is branded as a "quitter," and treated with contempt by

those who are around him. When the same workman returns to work on the following day, instead of

using every effort to turn out the largest possible amount of work, in a

majority of the cases this man deliberately plans to do as little as he

safely can ‑ to turn out far less work than he is well able to do ‑ in many

instances to do not more than one‑third to one‑half of a proper day's

work. And in fact if he were to do his

best to turn out his largest possible day's work, he would be abused by his

fellow‑workers for so doing, even more than if he had proved himself a

"quitter" in sport.

Underworking, that is, deliberately working slowly so as to avoid

doing a full day's work, "soldiering," as it is called in this

country, "hanging it out," as it is called in England, "ca canae," as it is called in Scotland, is almost

universal in industrial establishments, ad prevails also to a large extent in

the building trades; and the write assets without fear of contradiction that

this construes the greatest evil with which the working people of both

England and America are now afflicted. It will be shown later in this paper that doing away with slow working

and "soldiering" in all its forms and so arranging the relations

between employer and employe that each workman will

to his very best advantage and at his best speed, accompanied by the intimate

cooperation with the management and help (which the workman should receive)

from management, would result on the average in nearly doubling the output of

each man and each machine. What other

reforms, among those which are being discussed by these two nations, could do

as much toward promoting prosperity, toward the diminution of poverty, and

the alleviation of suffering? America

and England have been recently agitated over such subjects as the tariff, the

control of large corporations on the one hand, and of hereditary power on the

other hand, and over various more or less socialistic proposals for taxation,

etc. On these subjects both peoples

have been profoundly stirred, and yet hardly a voice has been raised to call

attention to this vastly greater and more important subject of

"soldiering," which directly and powerfully affects the wages, the

prosperity, and the life of almost every working‑man, and also quite as much

the prosperity of every industrial establishment in the nation. The elimination of "soldiering" and of the several causes of

slow working would so lower the cost of production that both our home and

foreign markets would be greatly enlarged, and we could complete on more than

even terms with our rivals. It would

remove one of the fundamental causes for dull times, for lack of employment,

and for poverty, and therefore would have a more permanent and far‑reaching

effect upon these misfortunes than any of the curative remedies that are now

being used to soften their consequences.

It would insure higher wages and make shorter working hours and better

working and home conditions possible. Why is it, then, in the face of the self-evident fact that maximum

prosperity can exist only as the result of the determined effort of each

workman to turn out each day his largest possible day's work, that the great

majority or our men are deliberately doing just the opposite, and than even

when the men have the best of intentions their work is in most cases far from

efficient? There are three causes for this condition, which may be briefly

summarized as: First. The fallacy, which has

from time immemorial been almost universal among workmen,

that a material increase in the output of each man or each machine in

the trade would result in the end in throwing a large number of men out of

work. Second. The defective systems

of management which are in common use, and which make it necessary for each

workman to soldier, or work slowly, in order that he may protect his own best

interests. Third. The inefficient rule‑of‑thumb

methods, which are still almost universal in all trades, and in practising which our workmen waste a large amount of

their effort.” Careful: Taylor isn’t suggesting workman are

soldiering because they are lazy – or any such similar idea. He is saying that they must

because they believe that to do so otherwise will result in; (1) loss or

work, or (2) increased effort for the same wages, or (3) that they are

unaware to wastage. Taylor

specifically addressed the wage/output issue via piecework, and the wastage

via various scientific approaches. The

second cause he clearly laid out as a result of “ignorance of employers. After

the intro, work through the early steel cutting experiments and summarize. Then

work through the manhandling calculations, use this to illustrate pursuit of

a paradigm Then

come back to how can we resolve these two different

approaches – leads into social Darwinism etc. Gilbreth,

Emerson, Taylor all working independently, coalesced as a consequence of

Taylor’s Shop Management paper (earlier than his Scientific Management

paper). “Scientific Management in its essence, consists of a certain

philosophy, which results, as before stated, in a combination of the four

great underlying principles of management:” Those

principles are; The

development of a true science The

scientific selection of the workman His

scientific education and development Intimate

friendly cooperation between the management and the men. Taylor

seemed to be driven by the conviction that “scientific” laws or truths

underlined common work practices if only they could be discovered. Maybe this was a consequence of his own

metal cutting experiments which did indeed furnish valuable empirical

relationships. We can see the drive

for this understanding in the following extract. “A large amount of very valuable data had been obtained, which enabled

us to know, for many kinds of labor, what was a proper day’s work. It did not seem wise, however, at this time

to spend any more money in trying to find the exact law which we were after.” Taylor

was looking for an exact scientific law to describe work or effort in terms

of mechanical energy expended. He had

found that; “On some kinds of work the man would be tired out when doing perhaps

not more than one-eight of a horse power, which in others he would be tired

to no greater extent by doing half a horse-power of work. We failed, therefore, to find any law which

was an accurate guide to the maximum day’s work for a first-class workman.” “Some years later, when more money was available for this purpose, a

second series of experiments was made, similar to the first, but somewhat

more thorough. This, however, resulted

as the first experiments, in obtaining valuable information but not in the

development of a law.” But

as we learnt on the page on paradigms it is often the insistence that a

paradigm is correct that lead at first to making further discoveries. Taylor is a nice example of this. Not deterred by two failures he presses on. “Again, some years later, a third series of experiments was made, and

this time no trouble was spared in our endeavor to make the work

thorough. Every minute element which

could in any way affect the problem was carefully noted and studied, and two

college men devoted about three months to the experiments. After this data was again translated into

foot-pounds of energy exerted for each man each day, it became perfectly

clear that there is no direct relation between the horse-power which a man

exerts (that is, his foot-pounds of energy per day) and the tiring effect of

the work on the man. The writer,

however, was quite as firmly convinced as ever that some definite, clear-cut

law existed as to what constitutes as full day’s work for a first-class

laborer, and our data had been so carefully collected and recorded that he

felt that the necessary information was included somewhere in the

records. The problem of developing

this law from the accumulated facts was therefore handed over to Mr. Carl G.

Barth, who is a better mathematician than any of the rest of us, and we

decided to investigate the problem in a new way, by graphically representing

each element of the work through plotting curves, which should give us, as it

were, a bird’s-eye view of every element.

In a comparatively short time Mr. Barth had discovered the law

governing the tiring effect of heavy labor on a first-class man. And it is so simple in its nature that it

is truly remarkable that it should not have been discovered and clearly

understood years before. The law which

was developed is as follows: The law is confined to that class of work in which the limit of a

man’s capacity is reached because he is tired out. It is the law of heavy laboring,

corresponding to the work of the cart horse, rather than that of the trotter. Practically all such work consists of a

heavy pull or a push on the man’s arms, that is, the man’s strength is

exerted by either lifting or pushing something which he grasps in his

hands. And the law is that for each

given pull or push on the mans’ arms it is possible

for the workman to be under load for only a definite percentage of the

day. For example, when pig iron is

being handled (each pig weighing 92 pounds), a first-class workman can only

be under load 43 per cent. of the day. He must be entirely free from load during

57 per cent. of the day. And as the load becomes lighter, the

percentage of the day under which the man can remain under load

increases. So that, if the is handling

a half-pig, weighing 46 pounds, he can then be under load 58 per cent. of the day, and only has to rest during 42 per cent. As the weight grows lighter the man can

remain under load during a larger and larger percentage of the day, until

finally a load is reached which he can carry in his hands all day long

without being tired out. When that

point has been arrived at this law ceases to be useful as a guide to a

laborer’s endurance, and some other law must be found which indicates the

man’s capacity for work.” (all page 26-27) What

can we learn from this? Well I think

that too often today the “science” in Scientific Management is

mis-understood. Taylor was definitely

seeking underlying explanations for management problems. He certainly did that with heavy lifting

and he certainly did that with metal cutting.

It we understand this we can see the basis for his 4 principles. What tends to happen today however, is that

the “science” is trivialized as the measurement part before hand. This is more a fault of a common

mis-interpretation of science rather than Taylor’s mis-application. However

the whole issue becomes clouded by Frank Gilbreth’s “time and motion” studies

of brick laying. Gilbreth developed

his mechanism independently of Taylor although it was subsequently fully

incorporated into the philosophy of Scientific Management. It is here that the confusion can arise

between time and motion studies and Taylor’s measurements required to distill

underlying fundamental principles. Gilbreth’s

approach was as follows (pg 61); “Find, say, 10 or 15 different men (preferably in as many separate

establishments and different parts of the country) who are especially skilful

in doing the particular work to be analyzed.” “Study the exact series of elementary operations or motions which each

of these men uses in doing the work which is being investigated, as well as

the implements each man uses.” “Study with a stop-watch the time required to make each of these

elementary movements and then select the quickest way of doing each element

of work.” “Eliminate all false movements, slow movements, and useless

movements.” “After doing away with all unnecessary movements, collect into one

series the quickest and best movements as well as the best implements.” “This one new method, involving that series of motions which can be

made quickest and best, is them substituted in place of the ten or fifteen

inferior series which were formerly in use.

This best method becomes standard, and remains standard, to be taught

first to the teachers (or functional foremen) and by them to every workman in

the establishment until it is superseded by a quicker and better series of

movements. In this simple way one

element after another of the science is developed.” Two

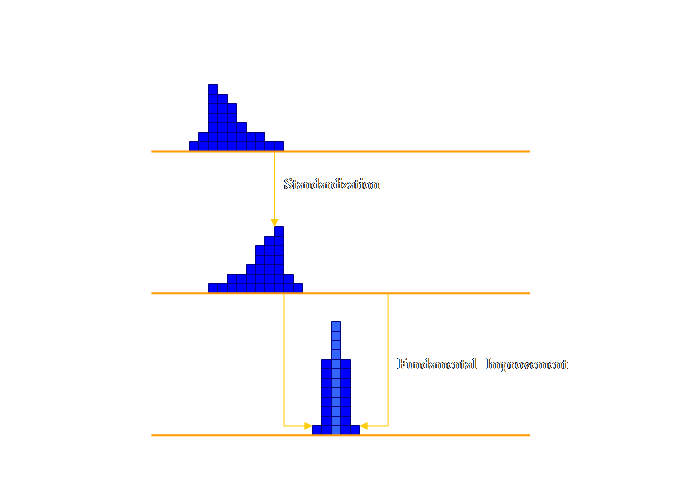

very important words occur in this quote; standard and supersede. Essentially Gilbreth sought to standardize

the process and then later on improve upon the standard. Let’s

try and draw this approach to make it clearer.

Today

we might simply call this benchmarking – although that is somewhat unfair

because there has been a systematic attempt to improve from removing waste –

whereas benchmarking can simply be following the leader without questioning

why they lead. Essentially we assume

that the job is being “done right.”

Taylor’s more fundamental approach went that step further, it asked if

this was the “right job.” If there was

a fundamental driver underlying the work that could lead to substantial improvement. We can

draw this as well.

Also

many of Taylor’s most common examples are localized; shoveling materials,

moving pig iron, inspecting ball bearings.

The optimizations were localized and the methodology reductionist. And

it is top down. Its

ironic that Taylor thought that workmen themselves were too dull to

understand the improvements Quote…. Also

machinists for some other reason Quote…. And

yet the first of his principles was to watch what first-class man does and

systematize that. Of

course in the case of machine shops Taylor had a very real and specialist

technical knowledge that was rare and could find immediate application. This placed him above the machinists in

machine shops but wouldn’t have delivered the same advantages in other

industries. To understand Scientific

Management we have to tease the specialist machine ship knowledge away and

examine the remaining system – the system that would be applicable to all

industries in general. Scientific

Management is a term that was coined late in the piece, at the urging of

Brandeis in 1910 during an Interstate Commerce Commission rate petition by

rail companies (pg 430). Yet to me

Taylor especially was an empiricist.

He sought to make rigorous observations and measurements and sift

through the resulting data looking for the underlying simplifying theory that

would account for the observations.

Once the underlying theory had been found he could use it to make

predictions for better outcomes in the future. The

metal cutting experiments and the material handling experiments are two

important contributions that Taylor made that are indeed scientific in their

approach and which warrant more attention than can be achieved on this

page. So here is a diversion for those

that are interested; Taylor II.

Also in this diversion I have highlighted the approach of Frank

Gilbreth, because this seems much less scientific and much more a

“standardization,” without any necessary theory behind it. This is important because the Gilbreths

were to survive Taylor by many years and I suspect that their reductionist

approach found its way more and more into the writings of “Scientific

Management,” diluting out the more difficult to understand systemic aspects

of Taylor’s approach. A

personal admission – I was looking for a smoking gun here. I can’t really tell why other than that the

time during which Taylorism was developing was also a time during which

Social Darwinism was an important force in American thought. Maybe I was alerted by the description of

the American Shirtwaist Company (@).

Maybe I was alerted by the apparent failure of American Industry to

head Deming’s message. Could there

have been other similar and earlier instances I wondered. In any event, there is a smoking gun that I

am glad to have found it. But it is

not where I expected to find it, and nor is it pointing in the “right’

direction, but it is exceedingly informative nonetheless. Let’s save the details for later. Well

Taylor doesn’t need a defense, he only needs people to hear and understand

what he actually said as opposed to what people interpreted that other people

thought that he said. Nevertheless I

am willing to put a defense forward because for one, it records a change in

my own perspective from the “paper cut-out” history that initially informed

the earlier pages of this website (but have been subsequently modified) to

the current position. Consider

the following; “In

the past the man has been first; in the future the system must be first. This in no sense, however, implies that

great men are not needed. On the

contrary, the first objective of any good system must be that of developing

first-class men; and under systematic management the best man rises to the

top more certainly and more rapidly than ever before (IV).” Time

for a personal admission. I thought

that Taylor and Scientific Management was all about exploitation of the

working classes. Isn’t that what he is

saying when he argues for “the greatest prosperity can exist only as the

result of the greatest possible productivity of the men and machines of the

establishment – that is, when each man and each machine are turning out the

largest possible output.” It would

certainly seem so at first reading.

Now, however, I am beginning to see that there is an underlying and

mis-interpreted context here – a context from a different time and for me a different

place that has to be examined in order to fully understand Taylor’s

intent. I will argue that Taylor, like

Deming, has been mis-interpreted and mis-applied since having been removed

from the original context. The causes

and the outcomes are similar in both cases.

Moreover, I think that what we can learn from these two precedents

stand to better inform us about the interpretation of Theory of Constraints,

if only we take the time out to listen. Taylor

is using the words “system” and that the true interests of labor (employees)

and capital (employers) are one and the same – congruence in our goal

alignment in other words. It seems

incredibly unlikely given the consistency of Taylor’s message that this is not

the intent. Doesn’t this also seem in

conflict with the desire for each man and each machine turning out the

largest possible output? And why in

Taylor’s time was it that within the industrial world employers and employees

were for war rather than peace? “No

one can be found who will deny that in the case of any single individual the

greatest prosperity can exist only when he is turning out his largest daily

output (2).” This is Taylor’s

statement to the effect that the whole is the sum of the parts. The

Industrial Context – Industrialization The

Social Context – Social Darwinism Make-to-fit

rather than make-to-tolerance. Pre

mechanization. Foreman contract

system. And although written quite

late – 1911 – The Principles of Scientific Management was prior to any of

Henry Ford’s attempts at mass-production.

Most examples are manual labor.

Only one (machine shop) suggests specialization. All are decoupled processes. Really just a step removed from the

previous water-powered mills of the %% & @@ century that was imported

into America from Europe (grist mills, saw mills, fulling mills, stamping

mills, etc.,) The stationary steam

engine via a power shaft and belts became the source of mechanical energy in

the machine shop. It

is into this social setting that Taylor arrived. Describe

Taylor. Quote

his what SM is not and what it is (a mind set). Then point out that Kanigel disparages this

idea – a too easy defense for failure of the methodology. I will argue that Taylor was correct. Taylor was arguing correctly, that the

content is not the context, without the context the content will fail to

deliver the full and intended results.

If

the proponents of a methodology or an approach or a philosophy are not

allowed to define the context of their philosophy and the context can only

defined by other people’s interpretation of the context, then we shouldn’t be

at all surprised to see these philosophies mis-applied and the results

wanting. What is lacking is the

discipline and rigor to investigate and understand the original context and

develop an empathy for it. We

have seen exactly the same thing in Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge,

and I will argue more fully in the next page that we currently see the same

effects in kaizen and lean. Without

doubt the same occurs with Theory of Constraints. We have shown as much on the page on

paradigms – the inability to recognize the new paradigm, not so much based

upon lack of knowledge, but based upon the block arising from previous

knowledge. Kanigel

also questions the legitimacy of Taylor’s understanding of his workmen. That Taylor from his position in society

worked on the floor for 4 years as a matter of choice and from the social and

financial security that he could return to and was unknown and unattainable

to his workmates. Personally I find it

difficult that Taylor could not have developed an understanding rather than

it would be difficult that he could have.

I

would suggest that you can’t work immersed in an industrial environment

without constant exposure to the language and emotion, the hopes and

aspiration, the failures and despair of the people around you – not unless

you are a psychopath – and there is no suggestion that Taylor was. If this were not the case we would have to

wonder how manager Ohno or academician Deming ever understood the people in

the systems that they work – and yet the evidence is that they manifestly did

understand. The

charge that Taylor didn’t consider his workman capable of making decisions

for themselves would not be unsurprising for many a modern worker in functional

hierarchies. That team-work and

empowerment should be in vogue today speaks volumes about how little we have

progressed in the last century. It

is through Gould and his story of two work sites - the Shirtwaist fire that I was

introduced to the concept of social-Darwinism and Spencerism – and thus an

historic context in which I was able to more completely understand – or

perhaps conjectorialize – the contemporary impact

of one Fredrick Winslow Taylor – the one right way, scientific management and

American culture at the turn of the 20th Century. Hofstadter,

R., (1959) Social Darwinism in American thought, revised edition, pg 40 “His first work, Social Statics (1850), was an attempt to strengthen

laissez faire with the imperatives of biology; it was intended as an attack

upon Benthanism, especially the Benthamite stress upon the role of

legislation in social reform. Although

he consented to Jeremy Bentham's ultimate standard of value ‑ the greatest

happiness of the greatest number of people ‑ Spencer discarded other phase of

utilitarian ethics. He called for a

return to natural rights, setting up as an ethical standard the right of

every man to do as he pleases, subject only to the condition that he does not

infringe upon the equal right of others.

In such a scheme, the sole function of the state is negative ‑ to

insure that such freedom is not curbed.” Hofstadter,

R., (1959) Social Darwinism in American thought, revised edition, pg 41 “... the main trend of Spencer's book was

ultra‑conservative. His categorical

repudiation of state interference with the "natural," unimpeded

growth of society led him to oppose all state aid to the poor. They were unfit, he said, and should be

eliminated. "the

whole effort of nature is to get rid of such, to clear the world of them, and

made room for better." Nature is

insistent upon fitness of mental character as she is upon physical character,

"and radical defects are as much causes of death in the one case as in

the other." He who loses his life

because of his stupidity, vice, or idleness is in the same class as the

victims of weak viscera or malformed limbs.

Under nature's laws all alike are put on trial. "If they are sufficiently complete to

live, they do live. If they are not

sufficiently complete to live, they die, and it is best they should

die." Spencer deplored not only poor laws, but also state‑supported

education, sanitary supervision other than the suppression of nuisances,

regulation of housing conditions, and even state protection of the ignorant

from medical quacks. He likewise

opposed tariffs, state banking, and government postal systems. He was a categorical answer to Bentham.” Into

this framework came Darwin. Hofstadter,

R., (1959) Social Darwinism in American thought, revised edition, pg 44 “With its rapid expansion, its exploitive methods, its desperate

competition, and its peremptory rejection of failure, post‑bellum America was

like a vast human caricature of the Darwinian struggle for existence and

survival of the fittest. Successful

business entrepreneurs apparently accepted almost by instinct the Darwinian

terminology which seemed to portray the conditions of their existence.” Hofstadter,

R., (1959) Social Darwinism in American thought, revised edition, pg 45 “The most prominent of the disciples of Spencer was Andrew Carnegie,

who sought out the philosopher, became his intimate friend, and showered him

with favors. In his autobiography,

Carnegie told how troubled and perplexed he had been over the collapse of

Christian theology, until he took the trouble to read Darwin and Spencer.” Here

is the social/scientific dogma for classism that Taylor is accused of being Hofstadter,

R., (1959) Social Darwinism in American thought, revised edition, pg 47 “The social views of Spencer's popularizers were likewise

conservative. Youmans took time from

his promotion of science to attack the eight‑hour strikers in 1872. Labor, he urged in characteristic

Spencerian vein, must "accept the spirit of civilization, which is

pacific, constructive, controlled by reason, and slowly ameliorating and

progressive. Coercive and violent

measures which aim at great and sudden advantages are sure to prove illusory." He suggested that, if people were taught

the elements of political economy and social science in the course of their

education, such mistakes might be avoided.

Youmans attacked the newly founded American Social Science Association

for devoting itself to unscientific reform measures instead of a "strict

and passionless study of society from a scientific view." Until the laws of social behavior are

known, he declared, reform is blind; the Association might do better to

recognize a sphere of natural self‑adjusting activity, with which government

intervention usually wreaks havoc.

There was precious little scope for meliorist activities in the

outlook of one who believed with Youmans that science shows "that we are

born well, or born badly, and that whoever is ushered into existence at the

bottom of the scale can never rise to the top because the weight of the

universe is upon him." Hofstadter,

R., (1959) Social Darwinism in American thought, revised edition, pg 50 “Spencer's doctrines were imported into the Republic long after

individualism had become a national tradition. Yet in the expansive age of our industrial

culture he became the spokesman of that tradition, and his contribution

materially swelled the stream of individualism if it did not change its

course. If Spencer's abiding impact on

American thought seems impalpable to later generations, it is perhaps only

because it has been so thoroughly absorbed.

His language has become a standard feature of the folklore of

individualism. "You can't make

the world all planned and soft," says the businessman of

Middletown. "The strongest and

best survive ‑ that's the law of nature after all ‑ always has been and

always will be." Don’t

contrast it here. But when you get to

Deming you must come back to this and constraint Deming’s systemic and

inclusive approach with the earlier one of Spencer and the individualists

(maybe Brandeis is the transition between the two. I’ve copied this to the page on Deming.) Actually Deming is before this. So maybe Organizations as Communities – or

later in this section after Brandeis).

Reiterate the irony that Goldratt/Deming arose in this “individualist”

environment. The Japanese reductionist

arose in their counter-reductionist or systemic environment. Because in a reductionist environment

systemism offers an effective improvement, and in a systemic environment a

reductionism offers an effective improvement. The

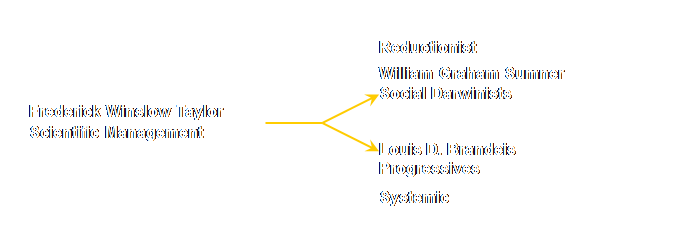

following is important (the first paragraph) because it puts in place the

logic for the previous diagram of TQC vs. TPK and the following (on this page

near this paragraph) Social Darwinists vs. Progressives and later Scientific

Management in the same frame. Hofstadter,

R., (1959) Social Darwinism in American thought, revised edition, pg 201‑202 “There was nothing in Darwinism that inevitably made it an apology for

competition or force. Kropotkin's

interpretation of Darwinism was a logical as Sumner's. Ward's rejection of biology as a source of

social principles was no less natural than Spencer's assumption of a

universal dynamic common to biology and society alike. The Christian denial of Darwinian

"realism" in social theory was no less natural, as a human

reaction, than the harsh logic of the "scientific school." Darwinism had from the first this dual potentiality;

intrinsically it was a neutral instrument, capable of supporting opposite

ideologies. How, then, can one account

for the ascendency, until 1890's, of the rugged individualist's

interpretation of Darwinism? The answer is that American society saw its own image in the tooth‑and‑claw

version of natural selection, and that its dominant groups were therefore

able to dramatize this vision of competition as a thing good in itself. Ruthless business rivalry and unprincipled

politics seems to be justified by the survival philosophy. As long as the dream of personal conquest

and individual assertion motivated the middle class, this philosophy seemed

tenable, and its critics remained a minority.” Taylor

recognized two forms of soldiering; Natural

loafing Systematic

soldiering Systematic

soldiering arose as a consequence of two things. Firstly the existence of

generation-to-generation rule-of-thumb knowledge transferal which essentially

means a lack of standardization – make-to-fit rather than

make-to-tolerance. Of course a counter

argument that isn’t entertained is what happened in the case of self-employed

workman outside the foreman contract system. Much

earlier in the page on OODA we mentioned in passing Boyd’s reference to

Fingerspitzengefuhl or fingertip feel.

Taylor is telling us exactly the same thing as follows; “It is not enough that a man should have been a manager in an

establishment which is under the new principles. The man who undertakes to direct the steps

to be taken in changing from the old to the new (particularly in any

establishment doing elaborate work) must have had personal experience in

overcoming the especial difficulties which are always met with, and which are

peculiar to this period of transition (pg 69).” Maybe

Taylor was ahead of his time, he understood change management to a degree

that is rare even today, to a degree that can only be earned by

experience. He had fingertip feel of

the situation. If

I really understand Taylor, then he was man of the floor. His piece work scheme was truly meant to

benefit both owner and employee. I

wanted Taylor to be a villain; instead I find myself some 6 years after first

reading his most recent biography as simply mis-understood. Someone whose reductionist approach was

removed from its systemic context by the prevalent dogma of the time –

social-Darwinism.

Next

Line

The

absence of subordination – in fact the very inadmissibility of local

inefficiency, tell us that although Taylor’s system was within a broader

systemic framework – the firm – it was ultimately reductionist. We

can trace this through the later developments of operations research to

systems thinking. In operations

research linear programming computations all of the parts of the model other

than the limiting factor can be reported in terms of sensitivity analysis –

the “slack” that is available in all non-binding parts without any due

consideration to any interaction between the non-binding parts. The

best evidence for this comes from one of Taylor’s contemporaries; Alexander

Hamilton Church (#). Church

was, as are we, interested that the efficient parts of a business added up to

a profitable whole. Church expressed

his argument in words that we have already assigned to the reductionist/local

optimum paradigm – the analytic (Taylor’s), and the systemic/global optimum

approach – the synthetic. “The main distinction between synthesis and analysis in this

connection is that synthesis is concerned with fashioning means to effect

large ends, and analysis is concerned with the correct local use of given

means… The view taken by analysis … is a narrow and limited one; it concerns

itself with the infinitely small. Its

task is to say “how to use certain means to best advantage.” … But the

synthetical side of management demands that every effort of analysis, like

every other effort made in the plant, shall have some proportion, some

definite economic relation to the purpose for which the business is being

run.” (Relevance Lost pg 52) Don’t

take this out of context, it isn’t a criticism of Taylor, it is a criticism

that costs as measures of local efficiency (ala Taylor) does not indicate

overall system effectiveness – the aim of Church in using cost data. It

seems reasonable given that Church made an explicit distinction between

analysis and synthesis, between the parts and the whole, that to some of

Taylor’s contemporaries there was no doubt that Scientific Management was a

reductionist approach (even though both Taylor and others such as Brandeis)

saw this reductionist approach within a broader systemic context. What

is Taylor’s approach as espoused in Scientific

Management, if it is not a win/win approach? Wheatley’s

comments are not so uncommon, but they are I believe mis-informed. If anyone deserves opprobrium it should be

the recent reengineering brigade; they are of our time and social context,

they had ample opportunity to learn from their own teachers (I am thinking of

Deming and Senge as examples) and others (I am thinking of the Kaizen

specialists in Japan) but they chose not to.

They chose to ignore the fundamentals of system-wide incremental

improvement in favor of slam-bam-thank-you-ma’am localized reductionist

innovation. How terribly sad. Maybe we should apologize for them because

within their academic isolation the response was (and still is) the paradigm

for Western improvement. Never mind

that time after time the resulting evidence is to the contrary. They are firm and consistent within their

beliefs. Taylor

too, was firm and consistent within his beliefs. We ought to not be frightened by his views

– they were incredibly common. To

place this within context, slavery was still common in Taylor’s youth and

there certainly those who strongly questioned it as there were those who

strongly supported it. We must be careful

in our criticism of past generations by holding them to our current values

because future generations will surely do the same to us. And now you see the rationale; we can’t

profess innocence against an accusation that has not yet been formed. Scientific

Management arose at an interesting time in our industrial development when

many basic changes were occurring. I

think that an important message to take out of this is that Taylor in his

later years was consistent in arguing for increased benefit to both employees

(even if as alleged he disdained them) and also employers. Moreover he recognized the broader

relationship of customer and society as a whole. That the Scientific Management philosophy

was embraced by the Progressives with no apparent complaint by the Society

for Scientific Management suggests to me that the intent of these people was

quite different from the actuality that was put in place by so many of the

individualists – both then and now. Refer

to the following in the scientific management section. Summary

– Standing On The Shoulders Of Giants Sometimes

it is a bit disconcerting to find that a recent personal discovery and new

found wisdom is really a recent rediscovery of some relatively older

wisdom. Accounting historians have

noted how all of the common approaches to financial and management accounting

and decision analysis were well formed by the early 1900’s. And so too, as we will find, much of the

operations expertise as well. It

should not be any surprise that the period that marks the rapid on-set and

development of serial production systems also marks the onset and development

of the fundamental contributions to accounting and operations management of

such systems. And far from being disconcerting

that much has been said and done before, it should be reassuring that such

problems were faced-up to and solved.

It is our job to not forget these earlier contributions and moreover

not to make mistakes that are already well known to a previous generation. Kanigel

suggests that “Taylor was not a profoundly original thinker, if by that we

mean someone who creates something new where nothing had been before (pg

19).” I will content that he was a

profoundly original thinker, not to be contrarian, but simply because so much

of Taylor’s work has been so absorbed into mainstream thinking (both systemic

and reductionist) that it seems as though it must always have existed. As one of his disciples said; “Not one of use dreamed that in less than a quarter of a century the

principles of scientific management would be so woven into the fabric of our

industrial life that they would be accepted as a commonplace, that plants

would be operating under the principles of scientific management without

knowing it, plants perhaps that had never heard of Taylor (pg 432).” Taylor

invented high speed steel. We have

little idea just how pervasive this product is within our own lives. Taylor discovered the underlying laws of

maximum effort. Taylor described a

systemic approach that was not seen again until Deming Car

Park Add the Ball’s pg 52 quote to the section on

industrialization – for tacit learning. Add the Toyoda quote to the section on

industrialization – for tacit learning. This is what Taylor railed against. Adam

Smith made a virtue of specialization in his analysis of pin production. However, we need to be careful, this was

written in what was really a pre-industrial manual manufacturing period. Moreover, it was about the deconstruction

of a task into a number of sub-divisible operations (sub-tasks). I’m tempted to say that maybe his vision of

specialization was of a different logical type than was then current, and one

that we certainly ascribe to today, but specialization of whole tasks is not

very new at all. The evidence for this assertion comes from

the discovery in 1991 of a 5000-year-old mummified corpse of a Neolithic man

in a melting glacier within the Tyrolean Alps (!). “Dressed in furs under a woven grass cloak, equipped with a stone dagger with an ash‑wood handle, a copper axe, a yew-wood bow, a quiver and fourteen cornus-wood arrows, he also carried a tinder fungus for lighting fires, two birch-bark containers, one of which contained some embers of his most recent fire, insulated by maple leaves, a hazel-wood pannier, a bone awl, stone drills and scrapers, a lime-wood-and-antler retoucheur for fine stone sharpening, an antibiotic birch fungus as a medicine kit and various spare parts. His copper axe was cast and hammered sharp in a way that is extremely difficult to achieve even with modern metallurgical knowledge. It was fixed with millimetre precision into a yew haft that was shaped to obtain mechanically ideal ratios of leverage. This was a technological age. People lived their lives steeped in technology. They knew how to work leather, wood, bark, fungi, copper, stone, bone, and grass into weapons, clothes, ropes, pouches, needles, glues, containers and ornaments. Arguably, the unlucky mummy had more different kinds of equipment on him than the hiker couple who found him. Archaeologists believe he probably relied upon specialists for the manufacture of much of his equipment ...” If

industrialization occupies approximately 1% of our recent and civilised past,

then it is clear that specialization occupies at least 50% of that time and

probably a great deal longer. We need

to be careful not to confuse industrialization and specialization, the two

...

(1)

Simons, R., (1995) Levers of Control. pp 21‑22 (2)

Liker, R., (2004) The Toyota Way, pp 143‑144 (3)

Liker, R., (2004) The Toyota Way, pg 197 (4)

Wheatley, M. J.,

(1999) Leadership and the new science, pg 159 (#)Johnson,

H. T., and Kaplan, R. S., (1987) Relevance Lost: the rise and fall of

management accounting. Harvard

Business School Press, pg 52. Car

Park Neave

pg 4 Somewhere address the commonality

of Gilbreth and the other scientific managers + Dr Walter Shewhart – all

working in America in the 1920’s. Neave

pg 4 A lack of understanding of variation often leads, despite all the good

intentions in the world, to making things worse instead of better. Start

Taylor with quote of “can’t find a good man” or rather juxtapose that next to

the same thing from Deming and then pose the question why nothing has changed

to show even more who similar the two are. Johnson,

H. T., (1992) Relevance Regained, pg 19 Accounting

historians have know for a long time that companies did not originally use

accounting systems as a source of management control information. Research in the historical records of

countless businesses, especially in manufacturing, shows that companies used

very sophisticated financial and nonfinancial management control systems

between the early 1800's and 1950.

However, the financial information in these systems seldom was derived

from accounting records, even though occasionally it was reconciled with

account data. Rather, financial

information used to control workers and companies' subunits consisted of cost

and margin information derived primarily from "bottom‑up" data about

work ‑ not primarily from "top‑down" accounting‑based information. “Even

the greatest of truths cab be overextended by zealous and uncritical

acolytes” Gould pg 256 Lying Stones of Marrakech. Raise

the question, why were the Japanese so attracted to Taylor (because they had

the same systemic approach. Johnson,

H. T., (1992) Relevance Regained, pg 197 But

underlying the new thinking required by these changes in business and in

governments is a pervasive theme in modern history ‑ how to balance the tension

between the dignity and rights of the individual and the power of the

community. A

Small Admission Let

me start with a small admission; I thought that Fredrick Winslow Taylor was

the devil incarnate. He was, according

to everything that I had read, the very epitome of reductionism – you may

indeed have picked up this flavor in earlier pages on this website. I am not going to change those pages any

time soon and I think that to be able to see a change in attitude is

important. What

brought on this change in attitude?